The party line: The Chinese Communist Party is waging a covert campaign of influence in Australia and while loyalists are rewarded, dissidents live in fear.

By Nick McKenzie, Richard Baker, Sashka Koloff and Chris Uhlmann

University student

Tony Chang had suspected for months that he was being secretly monitored, but it was a panicked phone call from a family member in China that confirmed his fears.

It was June 2015 and Chang’s parents had just been approached by state security agents in Shenyang in north-eastern China and invited to a meeting at a tea house.

It would not be a cordial catch-up.

As Chang later detailed in a sworn statement to Australian immigration authorities, three agents warned his parents about their son’s involvement in the Chinese democracy movement in Australia. The agents “pressed the point that my parents must ask me to stop what I am taking part in and keep a low profile,” the statement said.

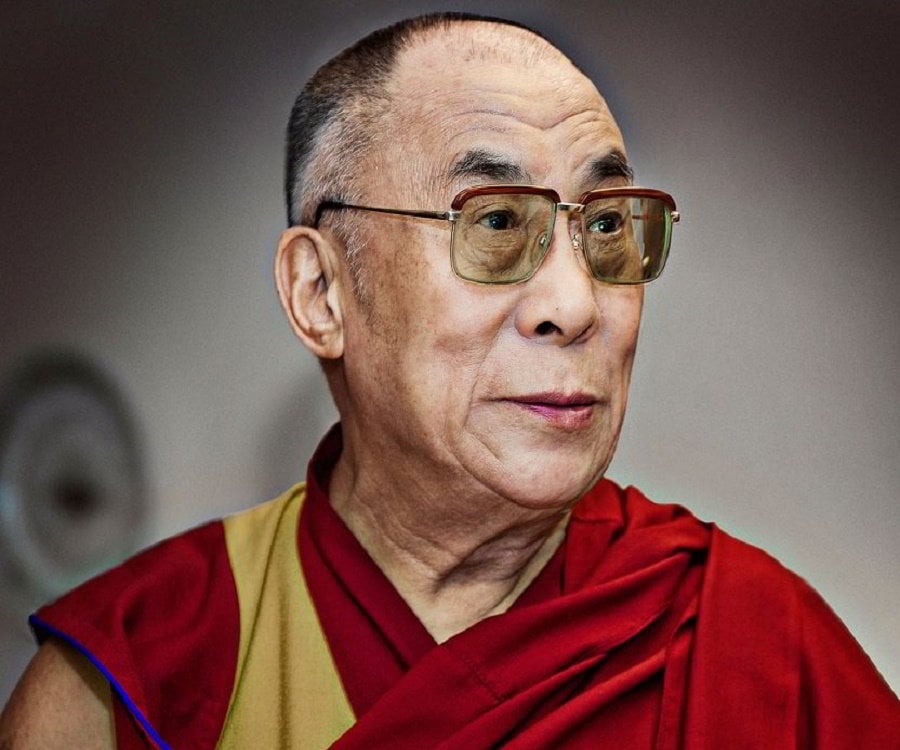

From a Brisbane share house littered with books and unwashed plates, the Queensland University of Technology student told a Fairfax Media-Four Corners investigation that the agents had intelligence about his plans to participate in a protest in Brisbane on the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, and also during the

Dalai Lama’s visit to Australia.

Chang’s activities in Brisbane meant that his terrified father in China feared that he too was being “watched and tracked”.

His father, a cautious, apolitical man, had already spent years worrying about his unruly son.

In 2008, when Chang was 14, he was arrested for hanging Taiwan independence banners on street poles in Shenyang.

His family was forced to call on Communist Party contacts to ensure Chang was released after several hours of questioning.

Tony Chang awaits questioning in a police station in China in 2008.

Tony Chang awaits questioning in a police station in China in 2008.

After Chang was questioned again in 2014 for dissident activities, he decided it was no longer safe to remain in China.

He applied for an Australian student visa.

The June 2015 approach to his parents back in China was the second time in two months that security agents had warned Chang’s family to rein in his anti-communist activism in Australia.

These threats helped convince the Australian government to grant Chang a protection visa.

Chang’s treatment as a teen is typical of the way the party-state deals with dissidents inside China. But the monitoring of the student in Brisbane and his decision to speak out about the threats to his parents in Shenyang, despite the risk it poses to them, provides a rare insight into something much less well known: the opaque campaign of control and influence being waged by the Chinese Communist Party inside Australia.

Tony Chang in Brisbane in 2017.

Tony Chang in Brisbane in 2017.

Part of this campaign involves attempts to

influence Australian politicians via political donors closely aligned with the Communist Party – something that causes serious concern to Australia’s security agency, ASIO.

But

the one million ethnic Chinese living in Australia are also targets of the Communist Party’s influence operations.

On university campuses, in the Chinese-language media and in some community groups, the party is mounting an influence-and-control operation among its diaspora that is

far greater in scale and, at its worst, much nastier, than any other nation deploys.

In China, it’s known as

qiaowu.

The recent chief of Australia’s diplomatic service,

Peter Varghese, who is now chancellor at the Queensland University, told Fairfax Media and Four Corners that

China’s approach to influence building is deeply concerning, not least because it is being run by an authoritarian one-party state with geopolitical ambitions that may not be in Australia’s interest.

“The more transparent that process [of China’s influencing building in Australia] is, the better placed we are to make a judgment as to whether it is acceptable or not acceptable and whether it is covert or overt,” Varghese says.

“This is an issue ASIO would need to keep a very close eye on, in terms of any efforts to infiltrate or subvert our system which go beyond accepted laws and accepted norms.”

The depth of the concern at the highest levels of the defence and intelligence establishment can be measured in recent public statements by the departing Defence Force Chief and the director general of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation.

Australia’s domestic spy chief

Duncan Lewis warned Parliament that

Chinese interference in Australia was occurring on “an unprecedented scale”.

“And this has the potential to cause serious harm to the nation's sovereignty, the integrity of our political system, our national security capabilities, our economy and other interests,” Lewis said.

A China expert, Swinburne professor

John Fitzgerald, agrees.

“Members of the Chinese community in Australia deserve the same rights and privileges as all other Australians, not to be hectored, lectured at, monitored, policed, reported on and told what they may and may not think.”

The coercion category

The definitive text on Beijing’s overseas influence operations is

Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese by China expert

James To.

Citing primary documents, To concludes

the policies are designed to “legitimise and protect the Chinese Communist Party’s hold on power” and maintain influence over critical “social, economic and political resources”.

Those already amenable to Beijing, such as many student group members, are “guided” – often by Chinese embassy officials – and given various benefits as a means of “behavioural control and manipulation,” To says.

Those regarded as hostile, such as Tony Chang, are subjected to “techniques of inclusion or coercion.”

Australian academic Dr

Feng Chongyi is another who falls into the “coercion” category.

In March, Feng travelled to China to engage in what he calls the “sensitive work” of interviewing human rights lawyers and scholars across China.

Feng expected to be closely watched and harassed when he arrived in Beijing but accepted it simply as an irritating feature of his job.

“It’s an open secret that our telephone is tapped, we are followed everywhere.”

“But that is a little thing that we have to accept if we want to work in China,” the University of Technology Sydney China scholar and democracy activist tells Fairfax Media and Four Corners.

Feng is a small, energetic man who has retained his Communist Party membership in the hope that he will live long enough to see some results from what has become his life’s mission: democratising China.

But he is also a realist, which meant he was initially unconcerned when, on March 20 and after he’d arrived in the city of Kunming, he was approached by agents from the Ministry of State Security. Feng was driven to a hotel three hours away to be questioned.

He expected the matter to end there but, a day later, he realised he was being followed by security agents to the sprawling port city of Guangzhou.

There he was told his interrogation would continue.

“That’s the time when I really realised something serious is happening,” he recalls.

Dr Feng Chongyi in 2017.

Dr Feng Chongyi in 2017.

Big trouble

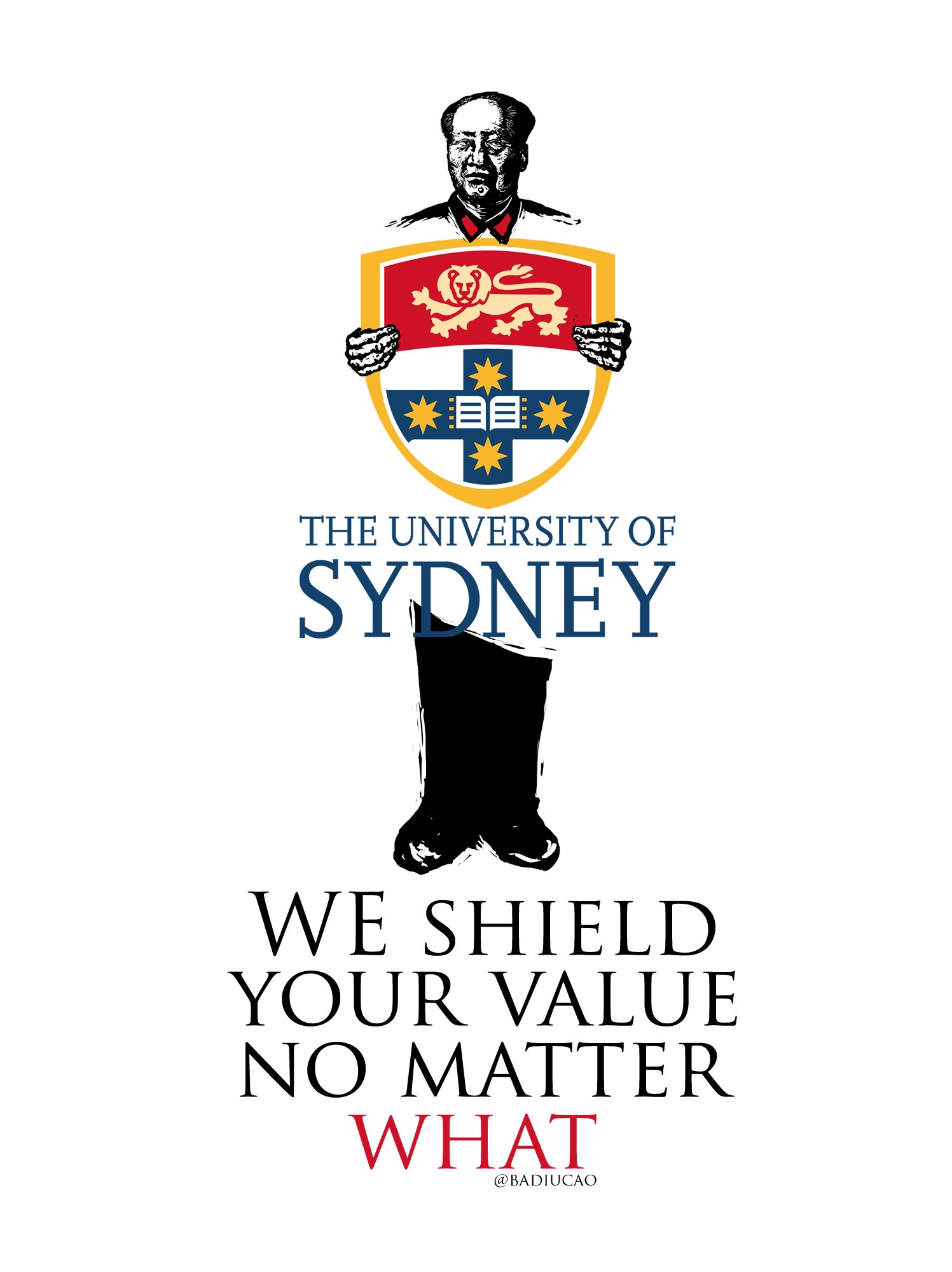

In a Guangzhou hotel room, the security agents subjected Dr Feng to daily six-hour questioning sessions, all of it video-taped.

Many of the questions were about his activities in Sydney, including the content of his lectures at UTS, the people in his Australian network of Communist Party critics, and his successful efforts to stop a concert glorifying the Communist Party founder Chairman

Mao Zedong.

Then the agents turned their attention to Feng’s family, asking him specific questions

to show him that his wife and daughter were also being closely watched.

He describes this change in tactics as a means of getting him to fully submit to his inquisitors’ demands.

It is the only part of his story that the wily academic hesitates to recall, as if emotion might overtake him.

“I can suffer this or that but I’ll not allow my wife and my daughter and my other family members [to] suffer from my activities,” he says.

“That is the thing that’s quite fearful in my mind.”

When his inquisitors demanded Feng take a lie detector test on March 23, he called his wife who told him to make a run for it.

A few hours later, after midnight, Feng crept out of his hotel, hoping to board a 4am flight.

But as he sought to check in, an airport official told him he could not leave China because he was suspected of endangering state security.

“At that point, my wife told my daughter that I was in deep trouble,” says Feng.

Feng’s daughter immediately called a foreign affairs specialist in the Australian government and asked for help.

Feng’s questioning continued for six more days until his daughter was contacted by an Australian government official and told Feng would be permitted to board a flight back to Australia.

In his final interrogation session, the MSS agents presented Feng with a document to sign that

forbade him from publicly discussing his ordeal.

But by then, his detention had already been covered by several Australian media outlets.

When Feng landed at Sydney airport on April 1, a small group of supporters was waiting for him with banners.

Feng believes his treatment in China was designed to send other academics, along with his supporters in the Chinese Australian community, a message to “stay away from sensitive issues or sensitive topics”.

“Otherwise they can get you into big trouble, detention or other punishment.”

Campus patriots

Mostly though, the Communist Party’s influence on Australian university campuses takes a subtler form, and works through the

Chinese Students and Scholars Associations.

The Communist Party targeted these patriotic associations after the Tiananmen Square student uprising as a way of maintaining control over overseas students.

In Australia, which has 100,000 Chinese students,

the associations are “sponsored” by Chinese embassy and consular officials.

Lupin Lu, an amiable 23-year-old communications student who is president of the Canberra University Students and Scholars Association, explains to Fairfax Media and Four Corners how Chinese embassy officials played an active role in organising a large student rally to welcome

Li Keqiang when he visited Australia in March.

On the day, the rally had two shifts, the first starting at 5am.

Lu insists it was students rather than the embassy calling the shots.

“I wouldn’t really call it helping,” she insists of the embassy’s role, while confirming it provided flags, transport, food, a lawyer and certificates for students that would help them find jobs back in China.

“It’s more sponsoring,” Lu explains.

Li Keqiang and Malcolm Turnbull in 2017.

Li Keqiang and Malcolm Turnbull in 2017.

Lu says her fellow students are willing to assemble at 5am to welcome Li because of their pride at China’s economic rise.

Other factors are an early education system that extols the virtues of the Communist Party and the reality that positive connections with the government can help a person land a job in China.

Federal police officers still describe with awe events in 2008 at the Olympic torch rally, when hundreds of chartered buses entered Canberra from NSW and Victoria, delivering 10,000 Chinese university students “to protect the torch”.

“If the Aussie embassy in London issued a similar call to arms to Australian students in London, there would be two students and a dog,” an officer says.

Lu had another way of motivating her fellow students to assemble before dawn: she stressed the importance of blocking out anti-communist protesters.

Would she go so far as to alert the embassy if a human rights protest was being organised by dissident Chinese students?

“I would, definitely, just to keep all the students safe,” she says. “And to do it for China as well.”

Going viral

The extent to which this student nationalism is directed and monitored from Beijing, and what this means for academic freedoms, is uncertain.

Last year, ANU Emeritus Professor and the founding director of the Australian centre on China in the World,

Geremie Barme, was so concerned

he wrote a lengthy letter to Chancellor Gareth Evans.

Barme’s fears were sparked by a

series of viral nationalistic videos created and posted by a Chinese ANU student, Lei Xiying.

One of Lei’s videos, “If you want to change China, you’ll have to get through me first”, attracted more than 15 million hits.

“I would opine that Mr Lei is an agent for government opinion carving out a career in China’s repressive media environment for political gain,” wrote Barme.

The ANU defended the student’s activities on free speech grounds, but Barme said

the university was ignoring Lei’s sponsorship by an authoritarian government that routinely threatens scholars and journalists.

“Make no mistake, it is officially sanctioned propaganda,” Barme said.

He urged the university to confront the issue by debating it openly.

His supporters say that request was ignored. Real media

Real media

A gracious host, Sam Feng is in a gregarious mood when he invites us to the headquarters of Pacific Times, the once proudly independent community Chinese-language newspaper he founded in the 1980s.

Over Chinese tea, Feng scoffs at suggestions that his paper is involved in financial dealings with an arm of the Chinese Communist Party that shapes its coverage.

“It is false. It is fake … They don’t need to do that,” says Feng, while insisting that questions of bias should be directed to Western media outlets whose coverage supports the US version of the world. “We are real media,” Feng explains of his small team of staff.

But corporate records suggest his paper is less independent than he claims.

Subsidiaries of the Communist Party’s overseas propaganda outlet, the Chinese News Service, own a 60 per cent stake to Feng’s 40 per cent in a Melbourne company, the Australian Chinese Culture Group Pty Ltd.

The results of this joint-venture deal appear evident in the newspaper’s content, vast chunks of which are supplied direct from Beijing where propaganda authorities control the media.

Academic Feng Chongyi describes

Pacific Times as one of several Australian Chinese-language media outlets that have forgone any semblance of editorial independence in exchange for deals offered by the Communist Party’s propaganda apparatus.

“It used to be quite independent or autonomous,” he says, “but ... you can see the newspaper now is almost identical [to] other newspapers that exclusively focus on the positive side of China.”

In a backroom in Sam Feng’s West Melbourne headquarters is evidence suggesting his Beijing dealings extend beyond what is placed in his newspaper.

A well-placed source leaked to Fairfax Media photos of dozens of placards resting against a wall of the room.

“We Against Vain Excuse for Interfering in South China Sea,” reads one of the placards.

![]()

To a casual observer, the placards would barely warrant a glance.

But along with other information provided by the source, they point towards what Australian security officials suspect: that

the Chinese Communist Party has had a hand in encouraging protests in Australia.

“The Chinese would find it unacceptable if Australia was to organise protests in China against any particular issue,” says former DFAT chief

Peter Varghese.

“Likewise, we should consider it unacceptable for a foreign government to be [encouraging], organising, orchestrating or bankrolling protests on issues that are ultimately matters for the Australian community or the Australian government.”

The placards stored at Pacific Times were handed out to hundreds of protesters who marched in Melbourne on July 23, 2016, to oppose an international tribunal ruling – supported by Australia – that rejected Beijing's claim over much of the South China Sea.

Of

Pacific Times owner Sam Feng, the source says the newspaper owner seeks to keep the Chinese Communist Party onside for commercial reasons: “He is a nationalist. But he just cares about business.”

A review of the corporate records of other large Chinese Australian media players reveals the involvement of Communist Party-controlled companies.

Those who turn down offers to become the party’s publishing partners and seek to print independent news face the prospect of threats, intimidation and economic sabotage.

Overseas forces

Don Ma, who owns the independent

Vision China Times in Sydney and Melbourne, tells Fairfax Media and Four Corners that 10 of his advertisers have been threatened by Chinese officials to pull their advertising.

All acquiesced, including a migration and travel company whose Beijing office was visited by the Ministry of State Security every day for two weeks until they cut ties with the paper.

Ma is happy to speak publicly because he has already been blocked from travelling to China.

His journalists, though, request their names and images not be used when we visit Ma’s Sydney and Melbourne offices.

They are fearful of retribution.

Ex-DFAT chief Peter Varghese and Swinburne Professor Fitzgerald says

Australia should require more accountability and transparency around the way the Communist Party and its proxies are operating in the media and on university campuses.

Fitzgerald warns

Communist Party influence operations in Australia not only risk dividing the Chinese community, but sparking hostility between it and other Australians.

“The Chinese community is the greatest asset we have in this country for managing what are going to be complex relations with China over the next decades – in fact for centuries to come – and we need them to help us in managing this relationship.

“If suspicion is sown about where their loyalties lie then we lose one of our greatest assets in this country now.”

The Vision China Times’ Don Ma has not only endured economic sabotage from the Communist Party but a campaign of vilification from pro-Beijing members of the local Chinese community.

Yet he keeps publishing, not only because he embraces freedom of the press but because many members of the disparate Chinese community urge him to keep doing so.

“The media here, almost all the Chinese media, was being controlled by overseas forces,” says Ma.

“This is harmful to the Australian society. It is also harmful to the next generation of Chinese. Therefore, I felt I wanted to invest in a truly independent media that fits in with Australian values.”

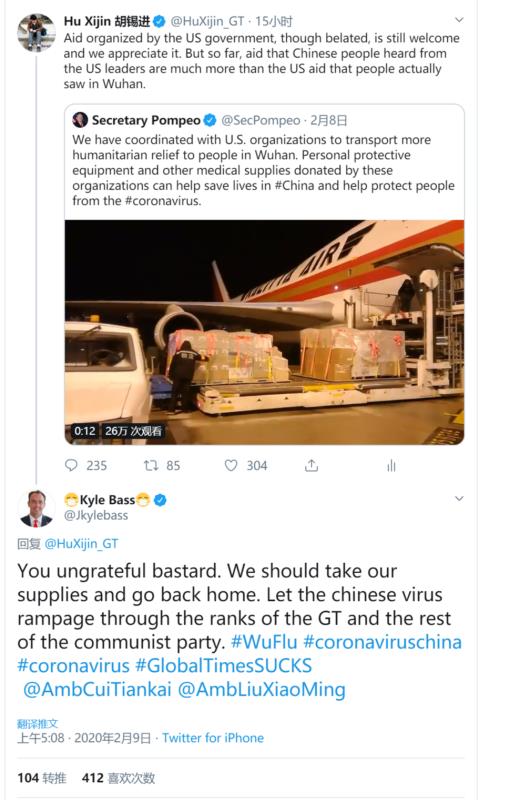

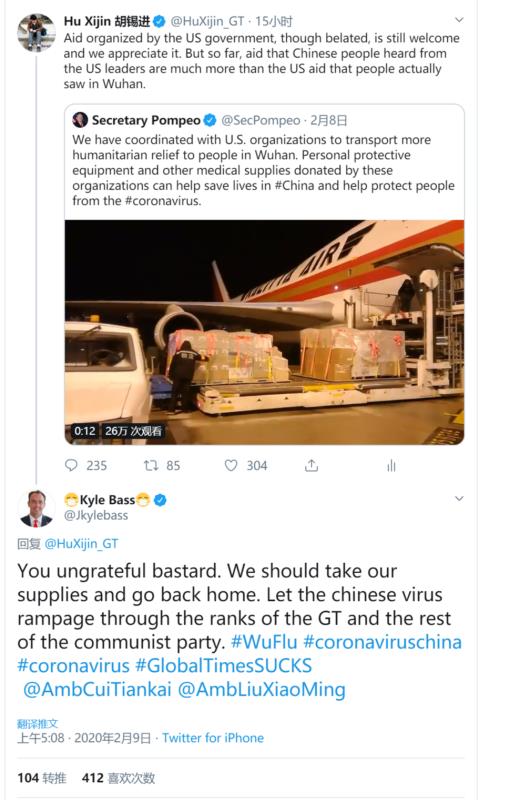

Kyle Bass

Kyle Bass

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi speaks at a Security Council meeting during the 72nd United Nations (U.N.) General Assembly at U.N. headquarters on September 20, 2017 in New York City.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi speaks at a Security Council meeting during the 72nd United Nations (U.N.) General Assembly at U.N. headquarters on September 20, 2017 in New York City.