How the fight for the next communications ecosystem could make a world dependent on Chinese technology, Chinese software, Chinese e-commerce, Chinese venture capital, and the Chinese market

By David P. Goldman

In 2013 my friend

Eduardo Medina-Mora became Mexico’s ambassador to the United States.

We had known each other since 1988, when I was preparing a study of Mexico’s tax and regulatory system for a U.S. consulting firm, and Eduardo was running a small Mexico City law firm after a stint as press officer for the Ministry of Fisheries.

We kept in touch over the years.

In 2003, when he headed Mexico’s foreign intelligence service, the CISEN, and I ran the fixed income research department of Bank of America, we compared notes over dinner in Mexico City.

He went on to serve as attorney general and other senior posts.

Eduardo complained that no one in the Obama administration seemed responsible for Mexico.

“We don’t even know who to call when a problem comes up,” he told me at his office at Mexico’s Embassy on Pennsylvania Avenue, where I called on him to offer my congratulations.

“It’s easier for [then Mexican President Enrique] Peña Nieto to get the president of China on the phone than Barack Obama. What would you advise me to do?”

A few months earlier I had joined Reorient Group, a Hong Kong investment banking boutique, as managing director in charge of the Americas.

I suggested that we remove the batteries from our BlackBerrys to prevent official eavesdropping.

We did so.

“You can invite the Chinese in to build a broadband network,” I then offered.

“That will get the attention of the Americans.”

It didn’t.

But I did get a look at how China’s strategy for global economic hegemony worked from the inside.

A year and a half and many machinations later I brought Mexican Ambassador Alicia Buenrostro Massieu to the headquarters of Huawei Technologies in Shenzhen.

Ambassador Buenrostro, the niece of a former finance minister whom I had known for years, came with as many of her Hong Kong entourage as would fit in a minivan.

The trip to Shenzhen took a bit less than an hour including a stop to pass Chinese customs.

The new bullet train from West Kowloon Station in Hong Kong to Shenzhen takes only eight minutes, one more technological wonder among the many that make some Chinese cities look like sets for science fiction films.

Huawei's highly-incentivized employees put in terrifying hours.

The Huawei campus covers 500 acres and makes Stanford University look dowdy.

The executive dining center features an enormous artificial waterfall, young women in traditional costume playing ancient Chinese instruments, and three-star quality Cantonese food (or so I’m told; I eat kosher).

We dined in a small private room with a Huawei executive, whence a guide escorted us to the exhibition hall.

We passed thousands of Huawei workers returning from lunch.

“They all have a futon under their desks,” said our guide.

“They take a nap after lunch because they work until 10 o’clock.”

The Huawei tour took three hours.

It might be the largest technology museum in the world, bigger than the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, or the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, except it shows only new things.

One exhibit consisted of a 4-by-6-yard wall map of Guangdong City, glistening tens of thousands of small lights.

“Every one of the lights is a smartphone,” said our guide.

“We can track the location of every phone and correlate position to online purchases and social media posts.”

And what do you use this information for, I inquired?

“Well, if you want to open a new Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise, this will help you to find the best location,” said the guide.

Yeah, right, I thought.

The Ministry of State Security knows where everyone is at all times and whom they are with; if the phones of two Chinese who posted something critical about the government are in proximity, the State Security computers will detect a conspiracy.

That was before China installed high-definition video cameras with facial recognition software powered by Huawei chips at 100-meter intervals in major cities.

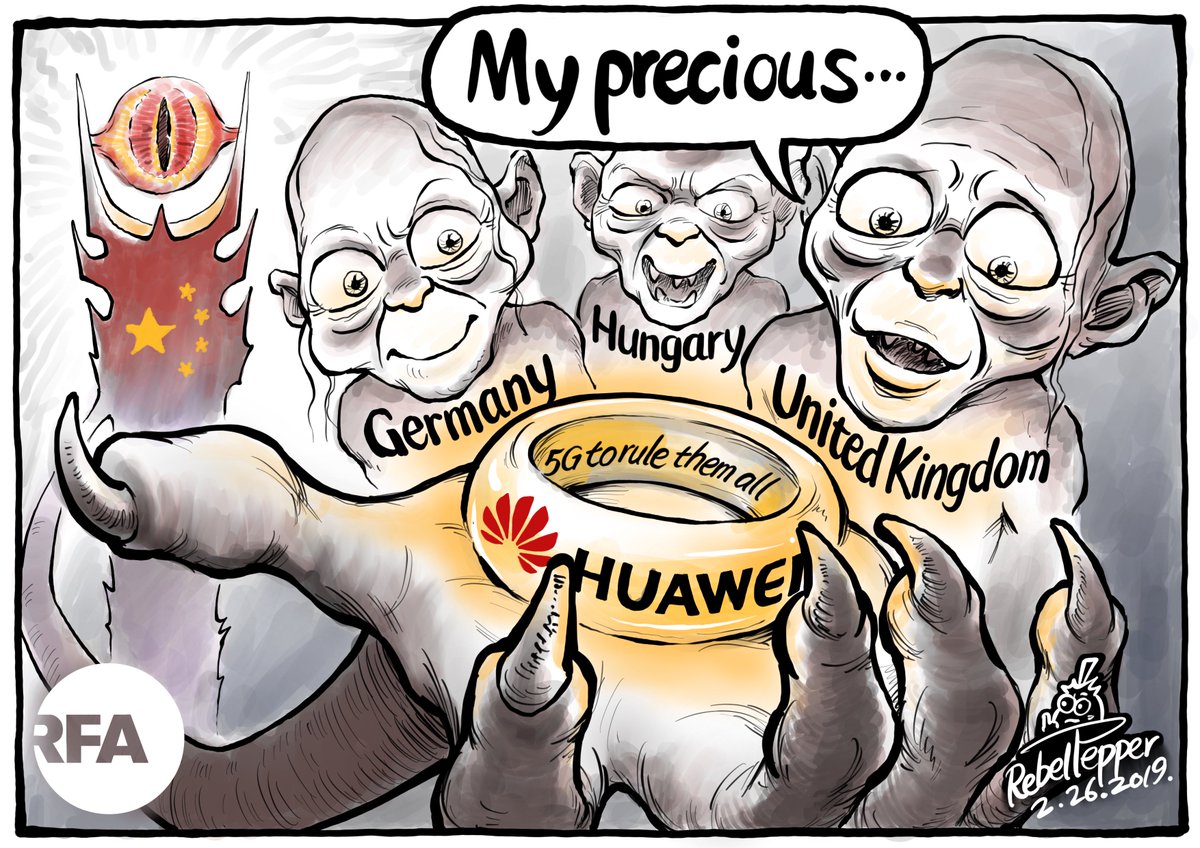

In response to Huawei’s domination of fifth generation broadband networks, the U.S. government is currently trying to isolate the company.

Secretary of State

Mike Pompeo on Feb. 21 warned that

the U.S. would cut off information-sharing with countries that use Huawei systems.

Last Dec. 1, while President Donald Trump dined with Chinese dictator Xi Jinping during the Group of 20, the Canadian government arrested Huawei’s chief financial officer at an airport transit lounge in Vancouver.

But I’m getting ahead of my story.

***

At the end of the tour, the Mexicans and I sat on a semicircular bench in a small amphitheater, and a young Chinese man stepped to the podium and turned on a projector.

You Mexicans have a big economy, he said, but very low broadband penetration, and he showed some charts and graphs to this effect.

Your economy is backward today, but you can become a great and rich economy, just like China.

Let us build a national broadband network for you, he urged.

Then we will bring in e-commerce and e-finance and create a whole new ecosystem that will make you a modern economy.

He sounded vaguely like the Borg: We will assimilate you.

Resistance is futile.

Ambassador Buenrostro was astonished.

After some time she asked, “How long have you been doing this?”

The man from Huawei said, “Oh, six or seven years.” Buenrostro said, “In Mexico, nothing ever changes.”

The United States is drifting toward the export profile of Brazil, with strength in agricultural commodities and energy but overall weakness in high-technology manufacturing and exports.

Not necessarily, though.

In 2014 and 2015 I traveled to Mexico to introduce Huawei executives to senior officials of Mexico’s Communications Ministry, hoping to land a role for Reorient Group in financing the project.

Reorient was a startup created by a Hong Kong entrepreneur whose business acumen and connections were impressive.

He helped to launch an Africa-centered logistics firm headed by Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater, with backing from CITIC, China’s largest financial firm.

Mexico might as well have been on the dark side of the moon where Reorient Group was concerned, but I wanted to follow the red thread and see where it led.

Since 2011, Huawei had been promoting the idea of national broadband networks as the centerpiece of a new economic “ecosystem,” flanked by the likes of Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, and other services firms.

Huawei’s mantra was the same that I had heard at their Shenzhen headquarters: Invite us in, and we’ll make you rich like China.

That wasn’t an idle boast.

In 1987, China’s per capita GDP was $251, according to the World Bank.

By 2017, it had risen to $8,894, or by 35 times.

Nothing like that had happened in all of economic history, least of all to the world’s most populous country.

And it isn’t just individual incomes that have risen.

China’s high-speed trains, superhighways, skyscrapers, urban mass transit, and ports are gargantuan monuments to the country’s new wealth.

They make American airports, railroads, and roads look like worn-out relics of the Third World.

Mexico was the first “developing country” I studied as an economic consultant; I would go on to Peru, Nicaragua, Russia and other countries before leaving the field in favor of relative value research on Wall Street.

The main thing you notice about developing countries is that they don’t develop—or if they do, only small parts of them develop.

Most people work a subsistence plot with poor implements, or they sit all day in a market stall waiting for someone to come along and buy a liter of cooking oil.

They barely make enough to eat, and they don’t pay taxes, which means that the government has no money to spend on infrastructure or services.

More than half of Mexico’s employment is what economists euphemistically call “informal,” that is, off-the-book businesses that have no access to capital.

East Asia is different.

The Chinese economic model is only a souped-up, bigger and more ruthless version of the Asian model that began with Japan’s restoration of the Emperor Meiji in 1868, and was replicated by South Korea and Taiwan: Move subsistence farmers to the cities and build factories for them to work in. While its per capita GDP rose 35 times, China moved 550 million people from the countryside to the cities, and it built the equivalent of all of the cities of Europe to house them.

Modernization in China isn’t the enclave of a middle-class modernity, as in India, but a movement that reaches into the capillaries of society.

Entrepreneurs in Chinese villages connect to the world market through mobile broadband, sell their products and buy supplies on the Alibaba platform, and obtain credit from microfinancing platforms. Information and capital flow down to the roots of the economy and products flow back up to the world market.

China now proposes to export its model to Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Latin America, parts of the Middle East and Africa.

This involves a Faustian bargain of sorts; the same technologies that have lifted billions of East Asians out of dire poverty and the ever-present risk of starvation into prosperity and economic security can also give dictatorial regimes previously unimagined tools for social control.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has a $1 trillion war chest for infrastructure investments and export loans.

In making such offers, Chinese planners are thinking a generation ahead.

The scarcest resource in the world is labor, specifically workers who can read an instruction manual, learn skilled or semi-skilled jobs, and show up for work on time.

Virtually all of the world’s population growth during the 21st century will take place in sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent—this last mostly in Pakistan, where the average female has four children compared with 2.2 in India.

The problem is that the productive parts of the world are all aging together.

There are plenty of young people in the world, but low educational levels, abysmal infrastructure and political instability sideline the regions where population growth is most rapid.

The people of aging countries with shrinking populations cannot find enough young people to absorb the investments they need to make to fund their prospective retirements.

China’s own labor force stopped growing a couple of years ago.

In 2018, kindergarten admissions in China fell by 740,000, the first decline on record, and the birth rate fell to 11 per 1,000 people in 2018 from 13 per 1,000 people in 2016.

The good news is that the prospects are good for a quantum jump in productivity in the developing world.

The bad news is that China is acting aggressively to position itself as the dominant equipment supplier, investor, joint venture partner and technology provider in this revolution.

By contrast, the United States is drifting toward the export profile of Brazil, with strength in agricultural commodities and energy but overall weakness in high-technology manufacturing and exports.

5G technology, a source of bitter contention between the United States and China, is a game changer. For the military, it makes possible the control of vast numbers of autonomous weapons systems, like drone swarms that can overwhelm anti-missile defenses.

For industry, it allows robots and control devices to exchange vast amounts of data at speeds 2,000 times that of 4G LTE.

It also cheapens the cost of delivering broadband to homes, by transmitting over the airwaves more data than fiber-optic cable now can carry.

Developing countries will therefore be able to go straight to 5G at much lower cost, and Huawei is both the cheapest and the most technologically advanced provider.

It spends $20 billion a year on R&D, about double the combined R&D budgets of its only major competitors, Sweden’s Ericsson and Finland’s Nokia.

Not since the invention of gunpowder has China led the world in the introduction of a disruptive new technology, and the United States still can’t believe that it has been leapfrogged.

For years the conventional wisdom held that the Chinese only could copy but not innovate.

That wisdom has now been proven wrong.

In 2003, Huawei admitted that it had

stolen code from Cisco, then the top producer of internet hardware.

But Cisco long since exited the hardware businesses, because the “capital light” services businesses offered higher margins.

Cisco presently has more than $70 billion of cash in the bank.

That’s roughly the whole of Huawei’s R&D budget for the past six years.

Why didn’t Cisco spend the money and maintain its dominant position in internet systems?

The answer lies in Huawei’s business model, which bids 40 percent below the nearest competition.

Its pricing power almost certainly depends on subsidized credit from China’s state-owned banks.

That money buys plenty of innovation.

***

When I first worked in Mexico City in 1988, Eduardo Medina-Mora’s little law firm employed a secretary who did nothing all day but dial the telephone, because it took five or six tries to get through to a local number.

By 2015 the system had improved, to be sure, but Mexico still had the most expensive broadband in the world and one of the lowest penetration rates (in subscriptions per capita) relative to the size of its economy.

Scrambling to get to a meeting at the Communications Ministry, I used Waze to direct the taxi driver, who did not use the program, because broadband was too expensive.

In 2015, Mexico announced that it would create a wholesale broadband network, the red compartida (shared network), that would lease broadband to any carrier that wanted it.

The consortium that won the bid to build the $7 billion network, ATLAN, engaged Huawei and Nokia to build the actual infrastructure.

The first elements of the network went live in March 2018.

By then, I was out of the picture.

In the summer of 2015, Alibaba’s billionaire founder, Jack Ma, bought Reorient Group through his private equity firm, Yunfeng Capital.

Early in 2016 he fired all of Reorient’s Western bankers, and there ended my Forrest Gump-like observations of great events in the broadband world.

But as the man with the PowerPoint at Huawei headquarters had told the Mexican delegation, it’s not about selling a broadband network.

It’s about the ecosystem.

As

Daniela Guzman reported in

Bloomberg News recently, “As America recedes into the background, Chinese foreign direct investment in Latin America and the Caribbean has skyrocketed over the last ten years, according to a 2018 report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. China dropped close to $90 billion in the region between 2005 and 2016. With a growing emphasis on telecommunications,

Chinese investment in emerging technology is increasingly the primary fuel behind Latin America’s tech boom.”

She quoted one South American entrepreneur saying, “When you go to China, you see what’s going to happen in Latin America in five more years. Today, we look at China. We look at Meituan, at Alibaba and Tencent, to see what we can do in the future.”

To get there, Latin American economies will depend on Chinese technology, Chinese software, Chinese e-commerce, Chinese venture capital and, of course, the Chinese market.

America’s intelligence agencies worry that China will use its dominance in 5G networks to steal data. That probably is true, but far more damaging to America’s position in the world is the prospect that the most productive countries of the Global South will be hard-wired into the Chinese economy.

Chinese domination of the Global South would leave America poorer and weaker than it wants to be, in a position comparable to Britain’s after the dissolution of its empire.

As Leon Trotsky once put it: You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.

The same applies to industrial policy.

The adoption of a Meiji-style model by a country of a billion and a half people has driven American companies out of most capital-intensive manufacturing industries.

I do not think that the United States should copy the Asian model, but we have our own precedents for an industrial policy of sorts: the great mobilization of American industry in World War II, the Apollo program, and the Strategic Defense Initiative.

When the Russians beat us into space with Sputnik in 1957, the Eisenhower administration responded with federal support for higher education in STEM.

Today only 7 percent of American undergraduates choose engineering as a major, compared with 33 percent in China.

We could also, in theory, unite with Japan, which has more foreign assets than China, and offer an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative “ecosystem.”

China is arrogant and predatory in its dealings with prospective economic clients.

We could do better.

The trouble is that we have trouble admitting to ourselves that China might best us.

We’ve told ourselves for years that the Chinese don’t invent but only steal technology, and that a state-directed system can’t possibly compete with our free enterprise model.

The West chronically underestimates Asians.

The Russians couldn’t believe that Japan could stand up to their battle-tested armed forces in 1905, when Japan crushed the Russians on land and sea at Port Arthur.

In his new biography of Winston Churchill, Andrew Robert reports that months before Japan took the British citadel of Singapore in 1942, Churchill “had privately predicted to the American journalist John Gunther that in the event of war the Japanese would ‘fold up like the Italians’ because they were ‘the wops of the Far East.’

Once again, recourse to racial stereotyping had led him badly to underestimate a determined foe. Churchill effectively admitted that he had been wrong when on 15 February 1942 he said in a broadcast, ‘No one must underrate any more the gravity and efficiency of the Japanese war machine. Whether in the air or upon the sea, or man to man on land, they have already proved themselves to be formidable, deadly, and, I am sorry to say, barbarous antagonists.’”

It’s time to stop underestimating China.

Underwater eyes on China.

Underwater eyes on China.

It is safe to say that the Pentagon and Google are very different places. But that gap could harm U.S. national security.

It is safe to say that the Pentagon and Google are very different places. But that gap could harm U.S. national security.