The New Gestapo

In November 2016, Interpol, the international police body, received its first Chinese president, Meng Hongwei.

This wasn’t strange: China is a member in good standing of the organization, and Meng, who had previously served as vice minister of public security in Beijing, was duly elected by its general assembly.

But Meng’s ascension also aroused suspicion because of China’s own record on blurring police work and politics — a pattern that will carry over into Interpol’s work.

Those simmering suspicions bubbled over this week.

After a Chinese billionaire based abroad threatened to reveal high-level corruption in his home country, Beijing rapidly requested and was granted an Interpol red notice against him — that is, an official request for his arrest and extradition issued by the intergovernmental organization that facilitates police cooperation among its 190 member countries.

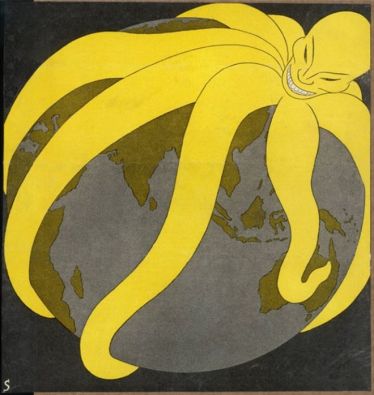

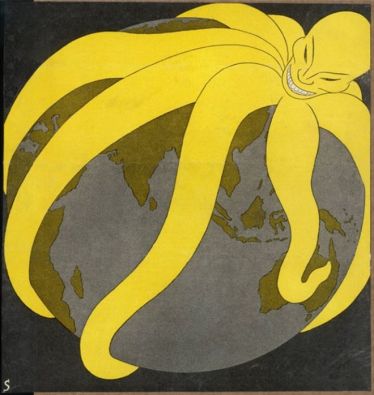

The timing gives reason to believe that China’s motive is purely political and that Interpol is becoming an extension of the increasingly long reach of the Chinese state.

In March, Guo Wengui, a charismatic real estate tycoon who left China two years ago and now resides in the United States, gave two interviews to a U.S.-based Chinese-language media outlet in which he claimed that one of China’s most powerful families has enriched itself by leveraging political connections to gain holdings in large companies.

Guo said he had learned through business dealings that the family of He Guoqiang, a former member of the Politburo, the highest ruling body in China, controlled a large but hidden stake in one of China’s biggest brokerage firms, and threatened to reveal further details of the He family’s wealth.

But his allegations went largely unnoticed until a New York Times investigation, published on April 15, traced the He family’s business holdings and backed up his claims.

Three days later, Interpol issued a red notice alleging that Guo had bribed a former top Chinese official who is now under investigation for corruption.

Beijing reportedly requested the red notice, according to anonymous sources who spoke to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman confirmed the news but took no responsibility, stating only, “We have learnt that the Interpol has issued a red notice on suspect Guo Wengui.”

Guo’s residence in the United States puts him out of the direct reach of the Chinese Communist Party — but not of harassment conducted through Interpol’s easily abusable system.

Interpol red notices are essentially a data-sharing mechanism between police forces in its member countries, allowing law enforcement to communicate internationally about wanted criminals.

The notices are not legally binding and are enforced differently in different countries, or not enforced at all.

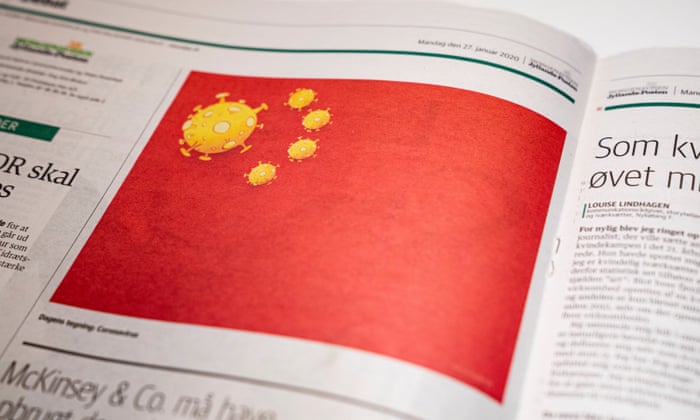

But some countries — Russia, the Central Asian nations, Turkey, Venezuela, and China — issue politically motivated red notices against dissidents, activists, and journalists.

Issuing such warnings, even if they do not lead to arrest, can harm the reputation of the targets, turn routine financial matters into criminal actions, and make it harder to live an ordinary life.

Interpol has previously refused to issue some red notices on the grounds that they involve purely political charges, such as the attempt by the Russian government to harass American-born whistleblower Bill Browder.

It’s no surprise that China is using every tool it can to go after Guo.

High-level corruption is a sensitive topic in China, where Xi Jinping has led a sweeping anti-corruption campaign and political purge that has felled some of the country’s most powerful political elites, including former security czar Zhou Yongkang and former military chief Xu Caihou.

The anti-corruption campaign has cemented Xi’s own power, sweeping away opponents and helping make Xi the most influential Chinese leader in decades.

He Guoqiang, however, has faced no official allegations of corruption; he was the top anti-graft official under former Chinese President Hu Jintao.

And the Chinese Communist Party wants to be the only judge of its members’ purity.

Charges of corruption originating outside the party against unauthorized targets are rarely tolerated.

China experts and human rights watchdogs suspect that is the true reason for the Interpol red notice — to silence an embarrassing critic.

“The 19th Party Congress is only about six months away,”

Bill Bishop, author of the

Sinocism newsletter and longtime observer of Chinese elite politics,

commented on April 19.

“Xi does not want to lose control of the narrative and any credible revelations of high-level infighting or corruption by the family of Wang Qishan” — another top official Guo mentioned in his interview — “could create enough noise to hinder Xi’s preferred personnel arrangements at the 19th Party Congress.”

In recent years, China has made use of red notices as it has expanded its anti-graft campaign beyond its borders.

In 2015, China hailed the issuance of

100 red notices against economic fugitives, largely as part of its “Sky Net” operation, which seeks to repatriate and punish corrupt Chinese officials and businesspeople who have fled abroad.

Chinese media have repeatedly emphasized the power of the Chinese authorities to reach anywhere in the world, broadcasting scenes of fugitives, such as former official Yang Xiuzhu, being escorted by police through Beijing’s airport.

“Interpol’s red notice system is vulnerable to weaponization by abusive regimes in the guise of criminal prosecution of dissidents, journalists, human rights defenders, and others fleeing persecution,” said Rebecca Shaeffer, a senior legal and policy advisor at Fair Trials, a Brussels- and London-based advocacy organization that has closely followed Interpol red notices for years, in an interview with Foreign Policy.

Interpol has several organizational flaws that make it particularly vulnerable to abuse.

Like the police bodies from which it’s built, the opaque organization is often unwilling to divulge information publicly.

Most red notices are not made public, and there is no public database to search the more than 100,000 notices in active circulation.

The evidence backing up the allegations is also frequently kept private, making it difficult to verify whether or not an alert is justifiable.

Until recent procedural reforms, it was difficult and time-consuming to get politically motivated red notices removed from circulation.

“What we can say is that the timing raises serious questions about the integrity of Interpol’s internal vetting procedures for issuing red notices,” said Nicholas Bequelin, Amnesty International’s regional director for East Asia, in a phone interview with FP.

The vast majority of notices are not politically motivated.

But those that are can be difficult to detect.

“Most of the time, if someone is wanted for a legitimate red notice, people stay hidden. They know that it’s for a valid arrest warrant,” Michelle Estlund, a Florida-based lawyer who specializes in defending against Interpol red notices, told FP in a phone interview.

“The people who come looking for assistance to deal directly with Interpol feel that the red notices issued against them are invalid.”

Estlund explained that it isn’t Interpol’s job to determine innocence or guilt when evaluating a request for a red notice.

Rather, it determines whether or not the requesting country has followed appropriate laws and procedures to request the notice.

“The tricky part is for Interpol to know this information when they receive the red notice. It’s almost impossible for them to know that,” Estlund said.

“There is a basic criteria that Interpol requires upon receipt of the application, and there is a review process in place, but for Interpol to review every application would be virtually impossible.”

In other words, the system is based in large part on trust — a trust that politically motivated red notices violate.

“China and Russia have abused the trust on which the system rests,” Bequelin said.

“Interpol does play a role in fighting international crime. If the system is broken and becomes perceived as a political tool, then it will hinder law enforcement efforts worldwide.”

But red notices are just one tool available to a Chinese state increasingly seeking to extend its influence over unruly citizens abroad — and they are highly effective, often resulting in frozen bank accounts and travel restrictions.

Others include threats, coercion, and kidnappings.

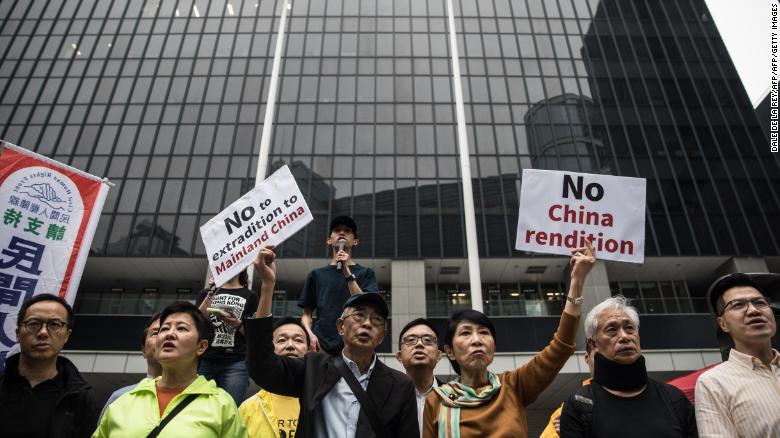

In 2015, four booksellers in Hong Kong and one in Thailand went missing.

All Chinese-born, the five men had published books containing information that Beijing deemed sensitive.

They later turned up in custody on the Chinese mainland.

Upon release, one described how he had been kidnapped and spirited over the border into the mainland without normal judicial procedure.

The kidnappings have cast a chill over Hong Kong, once believed to be beyond the reach of Chinese political oppression.

As a result, Meng’s election further alarmed international human rights advocates, including Bequelin.

“This is extraordinarily worrying given China’s longstanding practice of trying to use Interpol to arrest dissidents and refugees abroad,” Bequelin said at the time.

“Unlike most law enforcement agencies around the world, the Chinese police have a political mandate to protect the power of the Communist Party.”

The concern is that extralegal methods and political motivations are being merged within international rules and institutions and that, with a Chinese public security official in an influential position, Interpol’s bureaucratic incentives might tilt away from facilitating legitimate investigative work.

Estlund told FP that Meng’s election was concerning primarily due to the lack of sufficient rule of law or human rights protections in China.

“I think that anytime the leadership of a law enforcement organization like Interpol comes from a country where there are significant human rights concerns — of course that is going to be a concern,” she said.

“I would not say that that concern is limited only to this particular president. I would have a concern if the president hailed from any one of a variety of countries where there are routinely documented human rights violations.”

Chinese state-run media have suggested that Meng’s election will be a boon to the international expansion of China’s own anti-graft campaign.

One November 2016 article in the party-affiliated Beijing Youth Daily hailed Interpol as the most effective platform for combating international crime and pursuing stolen goods and highlighted how well that fit with China’s own recent emphasis on fighting corruption and recovering assets lost through corruption.

“Against this backdrop, a Chinese person has been elected as the head of Interpol,” continued the article, “which undoubtedly further reflects the recognition that Interpol and international society now give to China’s own rule of law.”

Another sign of Chinese influence over the international crime-fighting organization is the continued exclusion of Taiwan.

China claims sovereignty over the self-ruling island and has worked steadily to reduce its participation in international organizations where its membership might be seen as a sign of Taiwanese nationhood.

Interpol rejected Taiwan’s bid to participate in the November 2016 general assembly in which Meng was elected.

But Shaeffer expressed less concern about direct Chinese influence over Interpol, telling FP that the position of Interpol president is largely ceremonial.

“Meng Hongwei’s presidency of Interpol’s executive committee has brought attention to China’s history of using Interpol red notices to pursue dissidents, activists, and others who have fled its persecution over the years,” she said.

“But presidents of Interpol don’t have the power to issue alerts. That role sits with Interpol’s secretariat, who are bound by Interpol’s rules and constitution, which were beefed up at the end of last year to prevent abuse.”

The problem, according to Shaeffer, is that any country already has the ability to issue politically motivated red notices if desired.

“These rules must now be implemented and enforced to stop China from misusing this global crime-fighting tool,” she remarked.

Those rules have not yet seemed to protect Guo.

But the red notice hasn’t silenced him.

On April 19, he gave an interview to Voice of America in which he made further claims of corruption and misbehavior among several high-ranking Chinese officials and their relatives.

Whether he’ll be able to keep making those claims — and what other techniques Beijing will bring to bear against him — is another question.