By Jamie Seidel

Beijing wants to be an international super power.

To achieve this, it needs to carve out a vast swath of economic and military influence.

And it has a plan.

A recent US Defense Intelligence Agency analysis of China’s growing strength and expanding international ambitions judged Xi Jinping wants to project power far beyond its shores.

The China Military Power report delves into deep detail about what is known about Beijings capabilities and intentions.

“China is rapidly building a robust lethal force with capabilities spanning the ground, air, maritime, space and information domains designed to table to impose its will in the regional and beyond,” A DIA spokesperson told media at its launch.

Beijing is seeking to ‘unchain’ itself from what it sees as the shackles of Western cultural, military and economic dominance.

To do this, it has its eyes set on a series of five ‘island chains’ over which it seeks to exert its national interests.

Any one of them could be the spark of an international crisis.

And the talk has been getting tough.

The US Naval Base at Guam’s Apra Harbor.

RESTRAINING CHAINS

Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road initiative’ is an expansive project to connect China’s expansive economy with the rest of Europe and Asia.

But there are ‘choke-points’.

On land, the narrow mountain passes of China’s East Turkestan colony (where the suppressed ethnic Muslim Uighurs reside), along with Pakistan and Afghanistan, funnel road and rail traffic with the Middle East.

At sea, Singapore and the slender Malacca Straits is an unavoidable bottleneck in the flow of shipping between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

And then there is the small island democracy of Taiwan, the last outpost of pre-Communist China, acting as what Beijing believes as a link in a chain holding it back from the broader Pacific.

It already dominates what has been defined as the “First Island Chain”: the waters of the East and South China Seas following a rough ‘nine-dash line’ from Japan in the north, past Taiwan and the Philippines down to Singapore and Malaysia.

It’s achieved this through a rapid build-up of its navy and long-range strike aircraft, along with the internationally condemned construction of artificial island fortresses on remote reefs also claimed by neighbouring countries.

Now this victory of might over right has been achieved, analysts believe Beijing is setting out on its next objective: dominating the “Second Island Chain”.

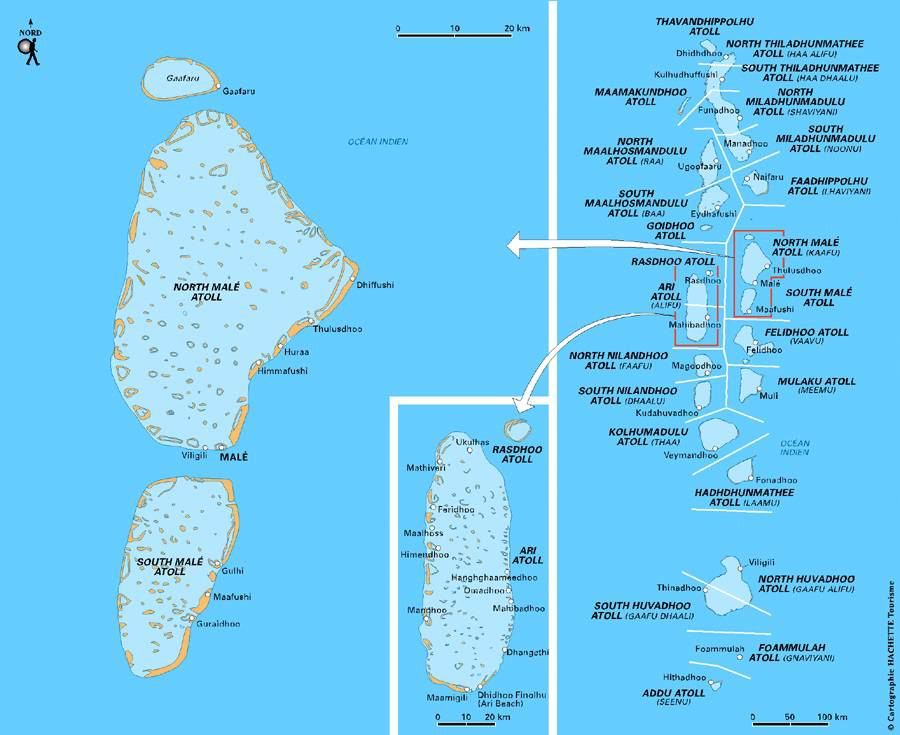

Meanwhile, it’s begun defining the next boundaries of its desired influence … a ‘Third Island Chain’ (encompassing Alaska, Hawaii and New Zealand), a ‘Fourth Island Chain’ (Linking Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldive Islands and the US/UK military facility at Diego Garcia in the midst of the Indian Ocean), and, finally, the ‘Fifth Chain’ extending from Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, past Madagascar to South Africa.

US strategic bombers on the island of Diego Garcia, in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

DANGEROUS IDEAS

Every island chain represents a sphere of influence over the nations they encompass.

Every island chain has at least one major US military base.

Every island chain is a potential flashpoint for international tensions.

All affect Australia: they fall to the north, east and west of the remote island nation.

But the nations most fearful of a dramatic shift in regional power dynamics from Washington to Beijing are Singapore and Japan.

Both could rapidly find themselves encompassed by seas dominated by China’s navy and skies by its air force.

Australia and New Zealand would soon follow.

But it’s the remote islands that are most at risk of conflict.

The United States has long since built up a strategy of using island bases to project power over a region.

Warships and combat aircraft can be based there.

But, most importantly, they can be used as launch pads for strong ground-based forces (such as troops and tanks).

Beijing has followed this line of thinking.

Its artificial island fortresses in the South China Sea are bristling with missiles, guns and military radars.

Their airfields and ports are military-grade.

They have strong garrisons.

All that is missing — for the time being — are permanently stationed combat aircraft and warships.

And it’s keenly aware of the strategic geographic importance of the Pacific island chains.

Which is why there’s a diplomatic land-grab underway.

Australia and the US have moved to head-off Beijing’s interest in Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, making a last-minute deal to reactivate the old World War II naval facility there as a forward operating base.

A recent change in government in Micronesia upset Beijing’s ambitions there, and resulted in what is in effect an economic embargo — the suspension of government-sanctioned holiday tours there.

It’s a similar story in the Indian Ocean, with a democratic change of government stifling Beijing’s growing economic dominance over the Maldive Islands.

Such ‘push-back’ has led some international affairs analysts, including in China, to suggest Xi Jinping has ‘overextended’ himself.

He’s moved too hard, too early — and is meeting an unexpected backlash over his plans to make China great again.

The question is: how will he react?

HMAS Choules pictured at the Manus Island Lombrum Naval Base, Paupa New Guinea. The US and Australia are planning a joint military facility there to stave-off Beijing’s interest.

THE NEXT CRISIS

China’s own 2015 Military White Paper outlines a mission statement: “It is a Chinese Dream to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. The Chinese Dream is to make the country strong …”

It’s already been enacting this mission through the building of extensive artificial island fortresses in the South China Sea, as well as establishing its first foreign military places at locations including Djibouti and Pakistan.

But military analysts are worried this expansion is set to accelerate.

With the European Union hobbled and distracted by a shambolic ‘Brexit’ divorce with the United Kingdom, and President Donald Trump’s insular ‘Make America Great Again’ perspective, Beijing has sensed an opportunity.

This has Australian, Singaporean and Japanese strategic think-tanks worried: can we rely on our treaties and relationships with the US, UK and Europe in the face of growing Chinese ambition?

Or will they retreat from their old island chains of influence?

The next real test will be the ‘Second Island Chain’.

This is defined as a wavy line starting in the middle of Japan, weaving through the scattered islands of Micronesia (including the major US military base of Guam) and down to the Indonesia’s Western New Guinea

Its growing naval and missile strength appears designed to project power at this scale.

Aircraft carriers can provide protection and strike power for naval formations.

Swarms of long-range guided missiles can force back larger US carrier battle groups.

Beijing’s already working to extend its diplomatic influence into the region.

As its hydrographic survey ships plough the waters to the north of Papua New Guinea and through Micronesia, it’s also pushing hard to establish a strong economic and diplomatic foothold in these Pacific states as well as the Philippines.

The major US defence facility on the Japanese island of Okinawa is grappling with deep unpopularity among the island’s residents.

Ties with Thailand are being cultivated, with talk of a possible canal to bypass Singapore.

And Xi is becoming increasingly vocal over ‘reunification’ with Taiwan — whether it wants it or not.

A recent US Defense Intelligence Agency analysis of China’s growing strength and expanding international ambitions judged Xi Jinping wants to project power far beyond its shores.

The China Military Power report delves into deep detail about what is known about Beijings capabilities and intentions.

“China is rapidly building a robust lethal force with capabilities spanning the ground, air, maritime, space and information domains designed to table to impose its will in the regional and beyond,” A DIA spokesperson told media at its launch.

Beijing is seeking to ‘unchain’ itself from what it sees as the shackles of Western cultural, military and economic dominance.

To do this, it has its eyes set on a series of five ‘island chains’ over which it seeks to exert its national interests.

Any one of them could be the spark of an international crisis.

And the talk has been getting tough.

The US Naval Base at Guam’s Apra Harbor.

RESTRAINING CHAINS

Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road initiative’ is an expansive project to connect China’s expansive economy with the rest of Europe and Asia.

But there are ‘choke-points’.

On land, the narrow mountain passes of China’s East Turkestan colony (where the suppressed ethnic Muslim Uighurs reside), along with Pakistan and Afghanistan, funnel road and rail traffic with the Middle East.

At sea, Singapore and the slender Malacca Straits is an unavoidable bottleneck in the flow of shipping between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

And then there is the small island democracy of Taiwan, the last outpost of pre-Communist China, acting as what Beijing believes as a link in a chain holding it back from the broader Pacific.

It already dominates what has been defined as the “First Island Chain”: the waters of the East and South China Seas following a rough ‘nine-dash line’ from Japan in the north, past Taiwan and the Philippines down to Singapore and Malaysia.

It’s achieved this through a rapid build-up of its navy and long-range strike aircraft, along with the internationally condemned construction of artificial island fortresses on remote reefs also claimed by neighbouring countries.

Now this victory of might over right has been achieved, analysts believe Beijing is setting out on its next objective: dominating the “Second Island Chain”.

Meanwhile, it’s begun defining the next boundaries of its desired influence … a ‘Third Island Chain’ (encompassing Alaska, Hawaii and New Zealand), a ‘Fourth Island Chain’ (Linking Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldive Islands and the US/UK military facility at Diego Garcia in the midst of the Indian Ocean), and, finally, the ‘Fifth Chain’ extending from Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, past Madagascar to South Africa.

US strategic bombers on the island of Diego Garcia, in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

DANGEROUS IDEAS

Every island chain represents a sphere of influence over the nations they encompass.

Every island chain has at least one major US military base.

Every island chain is a potential flashpoint for international tensions.

All affect Australia: they fall to the north, east and west of the remote island nation.

But the nations most fearful of a dramatic shift in regional power dynamics from Washington to Beijing are Singapore and Japan.

Both could rapidly find themselves encompassed by seas dominated by China’s navy and skies by its air force.

Australia and New Zealand would soon follow.

But it’s the remote islands that are most at risk of conflict.

The United States has long since built up a strategy of using island bases to project power over a region.

Warships and combat aircraft can be based there.

But, most importantly, they can be used as launch pads for strong ground-based forces (such as troops and tanks).

Beijing has followed this line of thinking.

Its artificial island fortresses in the South China Sea are bristling with missiles, guns and military radars.

Their airfields and ports are military-grade.

They have strong garrisons.

All that is missing — for the time being — are permanently stationed combat aircraft and warships.

And it’s keenly aware of the strategic geographic importance of the Pacific island chains.

Which is why there’s a diplomatic land-grab underway.

Australia and the US have moved to head-off Beijing’s interest in Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, making a last-minute deal to reactivate the old World War II naval facility there as a forward operating base.

A recent change in government in Micronesia upset Beijing’s ambitions there, and resulted in what is in effect an economic embargo — the suspension of government-sanctioned holiday tours there.

It’s a similar story in the Indian Ocean, with a democratic change of government stifling Beijing’s growing economic dominance over the Maldive Islands.

Such ‘push-back’ has led some international affairs analysts, including in China, to suggest Xi Jinping has ‘overextended’ himself.

He’s moved too hard, too early — and is meeting an unexpected backlash over his plans to make China great again.

The question is: how will he react?

HMAS Choules pictured at the Manus Island Lombrum Naval Base, Paupa New Guinea. The US and Australia are planning a joint military facility there to stave-off Beijing’s interest.

THE NEXT CRISIS

China’s own 2015 Military White Paper outlines a mission statement: “It is a Chinese Dream to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. The Chinese Dream is to make the country strong …”

It’s already been enacting this mission through the building of extensive artificial island fortresses in the South China Sea, as well as establishing its first foreign military places at locations including Djibouti and Pakistan.

But military analysts are worried this expansion is set to accelerate.

With the European Union hobbled and distracted by a shambolic ‘Brexit’ divorce with the United Kingdom, and President Donald Trump’s insular ‘Make America Great Again’ perspective, Beijing has sensed an opportunity.

This has Australian, Singaporean and Japanese strategic think-tanks worried: can we rely on our treaties and relationships with the US, UK and Europe in the face of growing Chinese ambition?

Or will they retreat from their old island chains of influence?

The next real test will be the ‘Second Island Chain’.

This is defined as a wavy line starting in the middle of Japan, weaving through the scattered islands of Micronesia (including the major US military base of Guam) and down to the Indonesia’s Western New Guinea

Its growing naval and missile strength appears designed to project power at this scale.

Aircraft carriers can provide protection and strike power for naval formations.

Swarms of long-range guided missiles can force back larger US carrier battle groups.

Beijing’s already working to extend its diplomatic influence into the region.

As its hydrographic survey ships plough the waters to the north of Papua New Guinea and through Micronesia, it’s also pushing hard to establish a strong economic and diplomatic foothold in these Pacific states as well as the Philippines.

The major US defence facility on the Japanese island of Okinawa is grappling with deep unpopularity among the island’s residents.

Ties with Thailand are being cultivated, with talk of a possible canal to bypass Singapore.

And Xi is becoming increasingly vocal over ‘reunification’ with Taiwan — whether it wants it or not.