China has retreated globally – not from its artificial islands in the South China Sea but economically and financially.

It seems just yesterday that the Middle Kingdom, as China calls itself, resembled an unstoppable juggernaut, cutting constructions contracts and buying properties all over the world.

That is no longer the case.

Trade war with the United States gets the credit, but even if Washington and Beijing were to sign a deal tomorrow, China would not regain its old momentum.

Official Ministry of Finance (MOF) figures, not surprisingly, offer a soothing picture of moderate decline, but private sources tell a much more dramatic story.

Official Ministry of Finance (MOF) figures, not surprisingly, offer a soothing picture of moderate decline, but private sources tell a much more dramatic story.

According to the American Enterprise Institute’s well-regarded China Global Investment Tracker (CGIT), Chinese overseas investments of all kinds in the first half of this year averaged only $27.5 billion, half the rate averaged during the same time in 2018 and barely a quarter the rate of 2017’s first half.

This year’s figures are lower than any time since 2008.

Construction contracts, largely in the third world as part of China’s Belt and Road initiative, have fallen off, too, but less dramatically.

China clearly has become much less engaged with the world than it was.

Two things have caused this retreat.

Two things have caused this retreat.

One is a growing hostility among host countries toward Chinese investment.

Especially developed countries, the United States in particular, have balked over the ugly Chinese practice of stealing technology.

Suspicions along these lines have held up approvals for Chinese purchases and other direct flows of funds.

Some familiar with Chinese practice have gone a step further.

The European Chamber of Commerce has warned against developing a dependence on China and Chinese funds.

This combination of concerns and suspicions have centered primarily on China’s huge state owned enterprises and less on private Chinese investment.

But if private investment has fallen off less dramatically, this growing reluctance in the West has had its effect there, too.

More significant is China’s relative shortage of hard currency.

More significant is China’s relative shortage of hard currency.

Despite Beijing’s efforts to make the yuan a global currency, it is little used in currency transactions – no more than 2% of the total in fact – and so is of little use in overseas purchases.

Meanwhile the trade war with the United States has already begun to cut into Beijing’s supplies of foreign exchange.

Beijing actually anticipated the problem and in 2017 began to ration foreign exchange even before the White House added any tariffs.

The first major investment declines occurred in late 2018, when the While House first imposed 10% tariffs on a range of Chinese products.

The next drop coincided with this past spring’s increased tensions.

To be sure, Beijing’s foreign exchange hoard remains huge, but officials are wary of how rapidly it has shrunk, falling some 25% from almost $4 trillion at its peak in 2014 to barely over $3 trillion during the first half of this year.

Beijing’s rationing of these financial resources has affected the state-owned sector in particular. Private companies have a greater willingness and ability to borrow hard currencies abroad.

Within the investment pullback, North America, which historically has accounted for some 17% of China’s overseas investment flows, has seen the biggest drop.

Within the investment pullback, North America, which historically has accounted for some 17% of China’s overseas investment flows, has seen the biggest drop.

No doubt, the hostility created by trade friction has played a role.

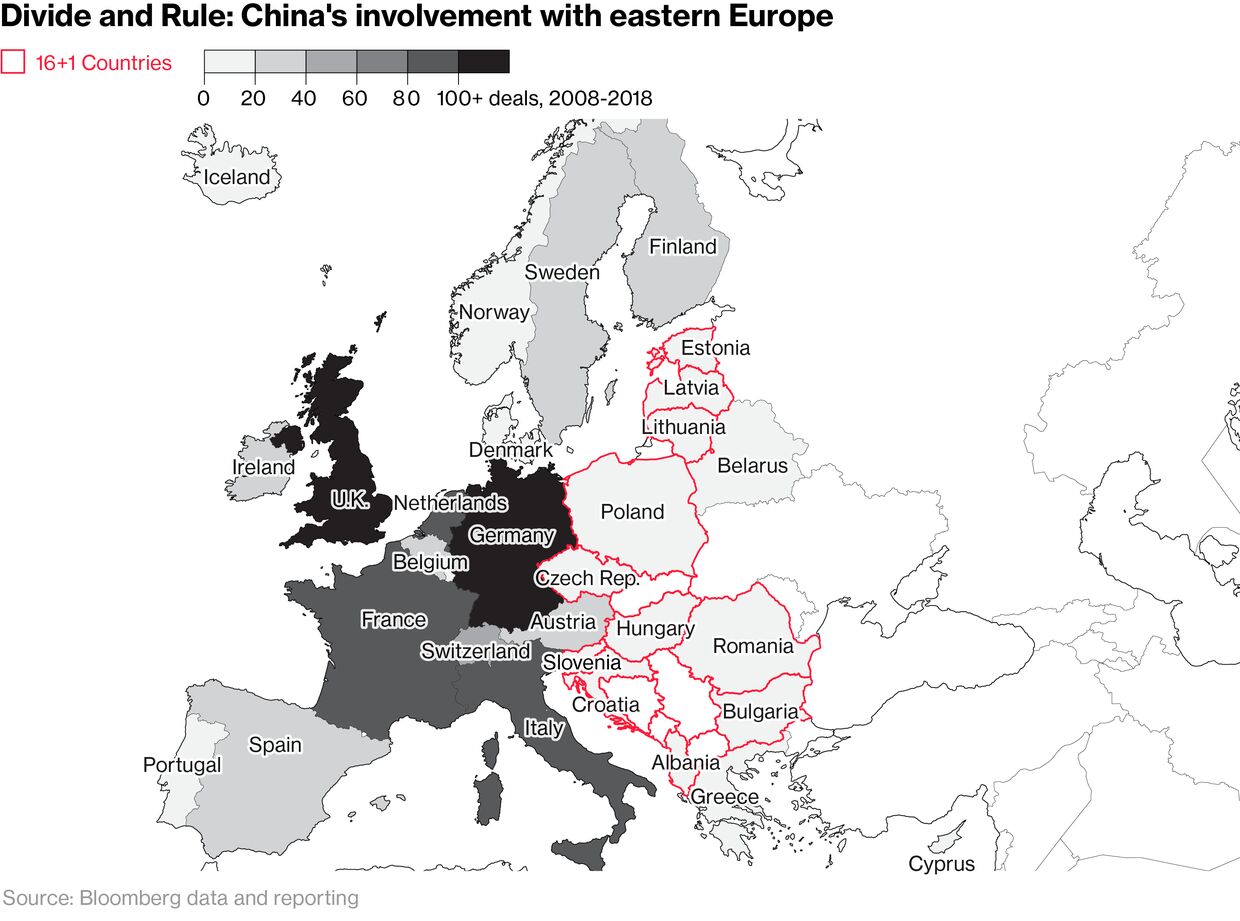

But China has also pulled back in Europe, where British and Swiss destinations have long dominated.

Australia and Singapore, which historically have accounted for about 10% of Chinese overseas investment flows, have seen less relative shortfall but some nonetheless.

China has concentrated its remaining financial resources on less developed countries.

China has concentrated its remaining financial resources on less developed countries.

The reasons are two fold.

First, activities in these countries center more on construction contracting than investing.

Such efforts may require subsidies, but they demand little hard currency.

Indeed, China collects fees on many of these projects.

Second, Beijing has clearly made its Belt and Road initiative (BRI) a political priority.

This effort at land trade routes between China on one side and Europe and the Middle East on the other may not generate the secure financial returns that investments in the developed world offer, but monies spent in these projects pay Beijing huge political dividends by tying these countries to China and by advancing a project that China has touted as an alternative to U.S.-led, mostly maritime trade arrangements.

BRI historically has captured more than three-fifths of China’s overseas construction volumes with almost three quarters of the monies involved in energy and transportation in such places as Pakistan and Iran, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria.

Preliminary figures for 2019 show that as all other efforts have diminished, BRI has captured a still larger proportion of China’s efforts.

Even if China and the United States were to sign a trade deal tomorrow, these trends would likely persist.

Even if China and the United States were to sign a trade deal tomorrow, these trends would likely persist.

Though trade would increase with a new treaty, the terms would no doubt create a more even balance than previously, making it highly unlikely that China could replenish its reserves of hard currency quickly, if at all.

At the same time, suspicions of Beijing’s agenda and practices, especially China’s state-owned enterprises, will persist, trade deal or no.

Political imperatives will, of course, keep China focused on BRI and its construction projects.

For the investment flows, the best to expect is stability.

It seems that for better or worse, the world has already seen the high water mark of Chinese investment flows.

Michele Geraci, Italy’s under secretary in the economic development ministry. “It is a very fertile area for investment,” he said of the potential influx of money from China.

Michele Geraci, Italy’s under secretary in the economic development ministry. “It is a very fertile area for investment,” he said of the potential influx of money from China.

Cheering after President Uhuru Kenyatta flagged off a cargo train for its inaugural journey to Nairobi on the Chinese-built railway last year.

Cheering after President Uhuru Kenyatta flagged off a cargo train for its inaugural journey to Nairobi on the Chinese-built railway last year.

Inspecting part of the railway in June.

Inspecting part of the railway in June.

Ceramic sea lions on the beach at Forest City.

Ceramic sea lions on the beach at Forest City.

Ant Financial’s Alipay: Rolling in Japan, but MoneyGram was off limits.

Ant Financial’s Alipay: Rolling in Japan, but MoneyGram was off limits. Gold bars are displayed at South Africa's Rand Refinery in Germiston.

Gold bars are displayed at South Africa's Rand Refinery in Germiston.  Too much of a good thing?

Too much of a good thing?