China’s use of technology for social control of its citizens is extensive – but it affects users elsewhere too

By Ian Tucker Chinese firms have signed deals with cities around the globe that include facial recognition software.

Chinese firms have signed deals with cities around the globe that include facial recognition software. Samantha Hoffman is an analyst of Chinese security issues at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (Aspi). She recently published a paper entitled Engineering Global Consent: The Chinese Communist Party’s Data-Driven Power Expansion.

Internet pioneers heralded a time when information would be set free, giving people everywhere unfiltered access to the world’s knowledge and bringing about the decline of authoritarian regimes… that’s not really happened has it?

Bill Clinton said that, for China, controlling free speech online would be like “nailing Jell-O to the wall”.

I wish he had been right.

But unfortunately, there was too much focus on the great firewall of China and not enough on how the Chinese Communist party was trying to shape its external environment.

When did China pivot from seeing the internet as a US-generated threat to something it could use to discipline and punish its own population?

It’s not just the internet, it’s technology in general.

When did China pivot from seeing the internet as a US-generated threat to something it could use to discipline and punish its own population?

It’s not just the internet, it’s technology in general.

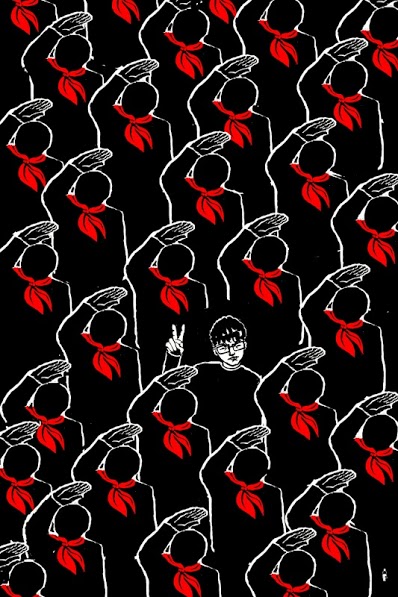

If you go back to even the late 1970s and early 80s, the way the Chinese Communist party (CCP) talks about technology is as a tool of social management.

It’s a way of not only coercive control, but also sort of cooperative control where you participate in your own management.

It’s this idea of shaping the environment, shaping how people think, how they’re willing to act before they even know they’re making a choice.

That’s the party’s idea.

When did that develop into what is called the social credit system?

Former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin spoke about this in 2000.

When did that develop into what is called the social credit system?

Former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin spoke about this in 2000.

He said we need a social credit system to merge rule by law and rule by virtue.

I don’t see it as different from the way Hannah Arendt describes how regimes attempt to make the law inseparable from ethics in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

How does the social credit system work for the average citizen? As they are going about their lives, are they continually earning and losing points based on their behaviour?

A pop cultural reference might be the Black Mirror episode Nosedive.

How does the social credit system work for the average citizen? As they are going about their lives, are they continually earning and losing points based on their behaviour?

A pop cultural reference might be the Black Mirror episode Nosedive.

But it isn’t the same.

It’s not really a number score that goes up and down.

There are multiple inputs.

So you have, say, legal inputs, like a court record, and financial inputs.

Then there are third-party inputs, such as surveillance video or data about your sentiment on social media.

The system includes blacklists, records on public websites, and platforms to support decisions on creditworthiness that integrate things like “sentiment analysis”.

This applies to companies and individuals.

Muji’s Shanghai branch had a mark of dishonesty on its credit record with the Shanghai government because one of its products was labelled “Made in Taiwan”.

The number of people affected is enormous: 17.5 million people were prevented from buying flights in 2018. Is there much pushback from the Chinese population about this system?

An average person might not see how it’s affecting them yet.

The number of people affected is enormous: 17.5 million people were prevented from buying flights in 2018. Is there much pushback from the Chinese population about this system?

An average person might not see how it’s affecting them yet.

Social credit is technology augmenting existing control methods.

So if you’re used to that system, you aren’t necessarily seeing the change yet.

Blacklists aren’t new, but the technology supporting this social management is.

And over time, as it becomes more effective, that’s where more people will notice the impact.

So there isn’t much concept of user privacy or anonymising data in China?

Privacy matters to the average Chinese citizen and there are privacy regulations in place.

So there isn’t much concept of user privacy or anonymising data in China?

Privacy matters to the average Chinese citizen and there are privacy regulations in place.

But privacy stops where the party’s power begins.

And so, you know, the party state might put controls on how companies can share data.

But again privacy stops where the party’s power begins.

And that’s a huge difference in the system.

One thing that’s interesting to keep in mind is the system itself.

One thing that’s interesting to keep in mind is the system itself.

When we think about China’s authoritarianism, we think about surveillance cameras, we think about facial recognition.

But we forget that a lot of the technology involved provides convenience.

And control happens for convenience.

Some of the technologies involved in increasing the party’s power are actually providing services – maybe Mussolini and his timely trains is a useful way of thinking about it.

Dr Samantha Hoffman, an expert on China’s cyber security operations.

The most egregious example of this surveillance technology would be in East Turkestan for controlling the Uighur [Muslim] population?

The most visibly coercive forms of what the party is doing are unfolding in East Turkestan.

Dr Samantha Hoffman, an expert on China’s cyber security operations.

The most egregious example of this surveillance technology would be in East Turkestan for controlling the Uighur [Muslim] population?

The most visibly coercive forms of what the party is doing are unfolding in East Turkestan.

It’s a virtual police state.

There are QR codes on people’s doors for when the party goes in to check on who is in.

Some researchers have found that if someone leaves through the back door instead of the front door, that can be considered suspicious behaviour.

Is the wider Chinese population aware of how the technology is being used in East Turkestan? Do they realise this is a more enhanced version of what we’ve got in their own lives?

I don’t think people are aware of how bad it is.

Is the wider Chinese population aware of how the technology is being used in East Turkestan? Do they realise this is a more enhanced version of what we’ve got in their own lives?

I don’t think people are aware of how bad it is.

A lot of people don’t believe Western reporting.

If they see it.

Even if they do believe it, propaganda has shaped a bad public opinion of the Uighurs.

Do you think the Chinese Communist party has a file on you?

I imagine that they probably have a file on a lot of outspoken researchers.

Do you think the Chinese Communist party has a file on you?

I imagine that they probably have a file on a lot of outspoken researchers.

I try not to think about what mine would look like.

In general, a lot of researchers on China have a fear, whether it’s conscious or unconscious, about losing access or the ability to go to China.

You have written about your fears that a commercial deal struck between Huawei and a Turkish mobile operator could be used to monitor the exiled Uighur population in Turkey.

Chinese tech giants like Huawei are signing agreements for smart cities globally – in April we at Aspi counted 75.

You have written about your fears that a commercial deal struck between Huawei and a Turkish mobile operator could be used to monitor the exiled Uighur population in Turkey.

Chinese tech giants like Huawei are signing agreements for smart cities globally – in April we at Aspi counted 75.

These agreements include public security, licence-plate and facial recognition tools.

As a local government you’re taking what is the cheapest and best product for your city.

You’re deploying it in ways you’ve decided are reasonable, but what might be forgotten is that these services require data to be sent back to the company to keep it up to date – and who else has access to that data once the manufacturer has it?

One agreement was made with Turkish mobile provider Turkcell.

Turkey has about 10,000 Uighurs living in exile – that system could be used to further control and harass exiles and family members in China.

More generally, I found that the party central propaganda department has made cooperation agreements with a number of major Chinese tech companies.

More generally, I found that the party central propaganda department has made cooperation agreements with a number of major Chinese tech companies.

As their products are bedded in they become ways of collecting tons of data.

A language translation tool, for instance, doesn’t sound like a surveillance tool but it’s a way to collect a lot of data.

Technically it’s not different from what Google does but their intent is different – it’s about state security.

So western governments should be wary of installing Chinese-designed tech infrastructure in their cities?

Yes.

So western governments should be wary of installing Chinese-designed tech infrastructure in their cities?

Yes.

It’s perhaps uncomfortable for a lot of people to acknowledge, but the party is very clear about its intent.

Its intent relates to state security.

The party talks about “discourse power” – the party’s version of the truth being the only thing that’s accepted.

The Chinese government ultimately controls all Chinese companies through its security legislation. You might be comfortable with someone collecting data to tailor advertising to you, but are you comfortable with sharing your data with a regime that has 1.5 million Uighurs imprisoned on the basis of their ethnic identity?

So we should be cautious about buying Chinese smartphones and smart home products?

I would be.

So we should be cautious about buying Chinese smartphones and smart home products?

I would be.

You may think “I’m not researching the CCP or testifying in Congress, so I don’t have anything to worry about”.

But you don’t really know how that data is being collected and potentially used to shape your opinion and shape your decisions, among other things.

Even understanding advertising and consumer preferences can feed into propaganda.

Taken together, that can be used to influence an election or feelings about a particular issue.

Some of these elements of monitoring and nudging are present in western life. For instance, fitness tracking that earns you discounts on health insurance, or local authorities using machine learning to identify potential abuse victims. Should we be careful about letting this stuff into society?

We need to be very careful.

Some of these elements of monitoring and nudging are present in western life. For instance, fitness tracking that earns you discounts on health insurance, or local authorities using machine learning to identify potential abuse victims. Should we be careful about letting this stuff into society?

We need to be very careful.

It’s easy to see what the benefits are, but we aren’t adequately defining the risks.

Some of the problems can be dealt with by introducing more data literacy programmes, so that individuals understand, say, the privacy issues concerning a home-security camera.

The Chinese party state is taking advantage of the weaknesses in liberal democracies, whether they’re legal or cultural.

The Chinese party state is taking advantage of the weaknesses in liberal democracies, whether they’re legal or cultural.

They take advantage of our really weak data privacy laws.

GDPR is a good step, but it doesn’t really deal with the core problem of technology that’s providing a service.

By its nature the company providing the service collects and uses data.