By Gwynn Guilford

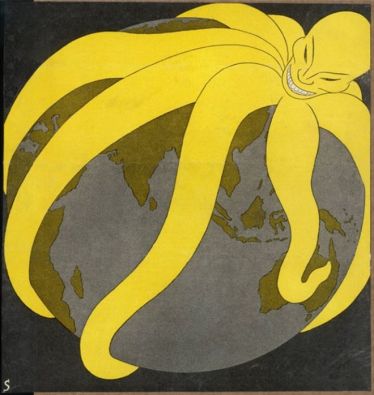

China has a master plan to oust the US as preeminent global superpower—and this time it just might work.

That’s according to the Washington Post’s David Ignatius (paywall), citing two Pentagon briefs.

“There’s an eerie sense in today’s world that China is racing to capture the commanding heights of technology and trade. Meanwhile, under the banner of ‘America first,’ the Trump administration is protecting coal-mining jobs and questioning climate science,” he concludes.

“There’s an eerie sense in today’s world that China is racing to capture the commanding heights of technology and trade. Meanwhile, under the banner of ‘America first,’ the Trump administration is protecting coal-mining jobs and questioning climate science,” he concludes.

“Sorry, friends, but this is how empires rise and fall.”

One of the studies Ignatius cites pegs funding for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—the signature plan of Xi Jinping to rebuild the old Silk Road trade route through central Asia—at $1 trillion.

The program will involve at least 64 countries.

By comparison, the Marshall Plan, through which the US established power in Europe after World War II, ponied up only around $150 billion in current dollars, primarily flowing to just six countries.

The “China is taking over the world” meme is a perennial one.

The “China is taking over the world” meme is a perennial one.

As usual, this argument overlooks what’s happening within China’s borders.

That includes: a credit-driven growth model that has left debt growing faster than the economy, the continued dominance of inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs) at the expense of dynamic private firms, and a fiscal system that depends on a housing bubble to sustain it.

These alarming economic problems limit the country’s future prosperity.

These alarming economic problems limit the country’s future prosperity.

But after Xi consolidated power, as expected, during October’s big party conclave, he has opted to use his now-official authority to double down on the policies that caused them in the first place.

At home and, increasingly, abroad.

Launched in 2013, BRI and its maritime complement—the $250 billion plan by which China will invest in ports in countries like Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Kenya—essentially absorb developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe into China’s industrial complex by funding infrastructure projects that use Chinese capital and labor.

Launched in 2013, BRI and its maritime complement—the $250 billion plan by which China will invest in ports in countries like Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Kenya—essentially absorb developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe into China’s industrial complex by funding infrastructure projects that use Chinese capital and labor.

Ignatius bemoans the rail line buildout connecting China to Europe and Eurasia while bypassing US-controlled sea lanes, but by exporting its short-term growth formula for wasteful investments abroad, Xi is compounding the already huge risk that befouls China’s financial system. China’s new Silk Road. (Reuters)

China’s new Silk Road. (Reuters)

Theresa Fallon, an expert on China’s relations with Eurasia, notes that many of the energy projects that dot the BRI map were completed long before the program’s launch.

China’s new Silk Road. (Reuters)

China’s new Silk Road. (Reuters)Theresa Fallon, an expert on China’s relations with Eurasia, notes that many of the energy projects that dot the BRI map were completed long before the program’s launch.

Others have quietly failed, she says.

“In the early days of the Belt And Road Initiative, it was easy to get Chinese bank loans if you said: ‘This is a Belt And Road project,'” Fallon told Radio Free Europe in May.

“So there’s a lot of what we call ‘white elephants’—or the local people call ‘red elephants’—along the Silk Road: projects that never took off, or were just abandoned or useless.”

For future projects, there’s the question of how they will generate enough to pay back Chinese banks. When it comes to trade, rail isn’t especially efficient compared with speedy air and cheap sea transport, Philip Bowring, a veteran Asia reporter, points out (paywall).

For future projects, there’s the question of how they will generate enough to pay back Chinese banks. When it comes to trade, rail isn’t especially efficient compared with speedy air and cheap sea transport, Philip Bowring, a veteran Asia reporter, points out (paywall).

“Of course, their mineral and oil exports need pipelines and railways, but these resources mostly have limited lives,” he adds.

The port projects make more business sense.

The port projects make more business sense.

Even so, some of the SOEs drafted into building this vast empire are balking at assuming the attendant political and financial risks.

Recipient countries, too, have plenty of reason for concern.

Recipient countries, too, have plenty of reason for concern.

Xi’s plan are aimed at solidifying new sources of demand abroad (in lieu of reforms that would restructure China’s economy to boost domestic demand)—in effect, breathing new life into China’s mercantilist trade strategy.

Tom Orlik, a Bloomberg Intelligence economist, estimates that in 2016, China ran a $250 billion trade surplus with BRI countries.

“It will be mathematically impossible for Sri Lanka and Pakistan to repay big yuan-denominated loans when they’re running trade deficits with China close to $2 billion and $9 billion, respectively,” notes Christopher Balding, an expert in China’s financial system.

Thanks to China’s size, running even a slight surplus means foisting massive deficits on its trade partners, as well as the debt and unemployment that accompany those, as we’ve argued before.

Thanks to China’s size, running even a slight surplus means foisting massive deficits on its trade partners, as well as the debt and unemployment that accompany those, as we’ve argued before.

And as Xi’s goal of self-sufficiency and manufacturing-export dominance—articulated in the Made in China 2025 plan, which focuses on Chinese dominance of artificial intelligence, robotics, and other high-tech sectors—makes clear, it’s not just BRI countries that will be on the receiving end of Chinese mercantilism.

More foreboding is the intensifying of the Party’s control of digital networks and personal information, and the spread of China’s tightly sealed internet into Africa and central Asia.

More foreboding is the intensifying of the Party’s control of digital networks and personal information, and the spread of China’s tightly sealed internet into Africa and central Asia.

Major vehicles for this “internet sovereignty” strategy are the Chinese tech companies once praised as the embodiment of dynamism and innovation.

Whether swearing fealty to Xi boosts the global competitiveness of Tencent, Alibaba, and the others may be revealing.

Even that campaign, however, works not by seizing the reins of the existing global order, but rather by expanding the reach of Xi’s central-planning regimes.

Even that campaign, however, works not by seizing the reins of the existing global order, but rather by expanding the reach of Xi’s central-planning regimes.

The core problem for China is: Power doesn’t guarantee competence.

And Xi’s handling of the domestic economy in the past half-decade suggests a dearth of the latter.

Not that Ignatius is wrong to worry about these developments.

Not that Ignatius is wrong to worry about these developments.

The more wealth China throws away on wasteful investments, the longer and more painful its process of economic rebalancing will be—for its people and the global economy.

And as Ignatius rightly argues, America’s global leadership is indeed crumbling (evident in the simple fact that China has been able to dragoon so many infrastructure-starved countries into its Faustian world-order underbelly).

And while the dimming of American influence predates Donald Trump, he seems plenty keen on hastening it.