Take Defense Treaty Action For Philippine Sovereignty In South China SeaBy Anders Corr

On Monday, Reuters

reported China Coast Guard and industrial fishing ship operations at

Scarborough Shoal, the Philippines, which are arguably a violation of Philippine territorial sovereignty.

The report said China is now allowing Philippine fishermen at the shoal, but restricting full access to the lagoon.

The ratio of Chinese to Philippine fishing boats on Monday was about 10:1.

China Coast Guard are typically

armed, and have been shown to be armed at the shoal.

Chinese ships at the shoal on Monday included at least two approximately 75-meter industrial fishing trawlers.

In addition, according to Reuters, the Chinese Foreign Ministry

confirmed that the China Coast Guard was at the shoal to “administer fishing and preserve the peace.”

This is arguably a direct violation of Philippine sovereignty at what the Hague’s

Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) found to be an

“island” last year.

The U.S.-Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty of 1951 applies to “islands”, so should be triggered by China’s continued armed occupation of Scarborough.

A Filipino fisherman is seen past the US Navy amphibious transport dock ship USS Green Bay.China’s occupation is an affront to the Philippines’ sovereignty, territorial integrity , and the

Constitution of 1987, according to which “The State shall pursue an independent foreign policy. In its relations with other states the paramount consideration shall be national sovereignty, territorial integrity, national interest, and the right to self-determination,” and that “The State shall protect the nation’s marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and exclusive economic zone , and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.”

If allowed to continue,

Chinese occupation of the shoal degrades the Philippine environment, sovereignty, and the likelihood that it will eventually regain control of the shoal.

The longer China has control of the shoal, the more likely it is to build planned military facilities there, and the less likely it will return the shoal to the Philippines.

It is critical for the natural habitat at Scarborough, and for the Philippines’ sovereignty and territorial integrity, that the Philippines, U.S., and allies immediately increase pressure on China, through economic sanctions and activation of the defense treaty if necessary, to vacate the shoal and return it to Philippine administration.China is in the process of large scale environmental destruction at Scarborough Shoal and other parts of the South China Sea (SCS),

including through widespread destruction of endangered coral and harvesting of endangered species such as giant clams and sea turtles.

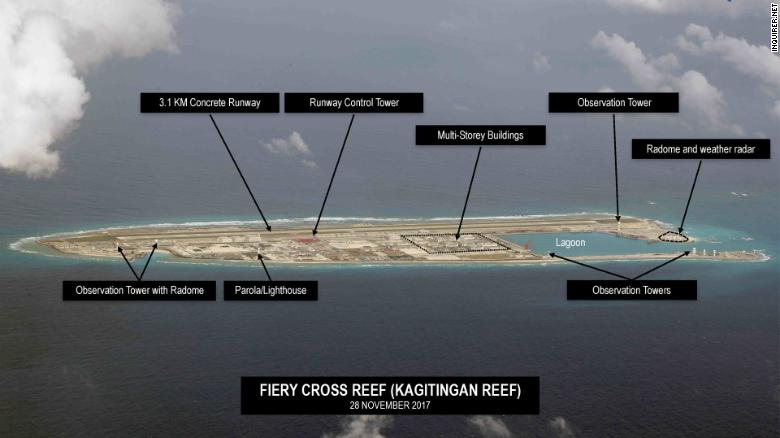

China has been turning barely-submerged shoals in the South China Sea into militarized artificial islands, replete with military runways and docks large enough for aircraft carriers and nuclear missile submarines.

Analysts think China may eventually create underwater submarine

bastions or harbors in the South China Sea, including at

Mischief Reef and Scarborough.

A Chinese military source and maritime experts said last year that China plans to turn Scarborough into a military base. This picture taken on April 23, 2016 shows a member of the Indonesian navy standing before the Chinese trawler ‘Hua Li-8′.

This picture taken on April 23, 2016 shows a member of the Indonesian navy standing before the Chinese trawler ‘Hua Li-8′.

I visited Scarborough Shoal in June 2016,

Philippines Independence Day, on a “Freedom Voyage” organized by the Kalayaan Atin Ito activist group.

Two 2,580-ton China Coast Guard cutters with light cannon, and another medium-sized China Coast Guard boat, made numerous dangerous passes, charges, chases, and blocking maneuvers of our 30-meter wooden fishing boat.

In one case, the medium-sized China Coast Guard boat charged us to about 4 meters, then began rocking in a way that made our boat pitch violently up and down.

Once we made it past the larger Coast Guard boats to the shoal, Filipino activist swimmers carrying Philippine and U.N. flags swam towards the shoal, and could have been killed on multiple occasions as two China Coast Guard speed boats circled them aggressively and backed their spraying propellers towards the swimmers within about 3 feet of slicing into their flesh.

Over the course of about an hour, five very brave swimmers were undeterred, and as swimmer and leader of the expedition

Joy Ban-eg diverted two China Coast Guard speed boats, from which she was forced to push off on multiple occasions, swimmer

Mariel Ipan made it past the Chinese to raise a small

Philippine flag on the shoal that day.

I was there and I saw it happen.

The next day, Ms. Ipan

wrote on Facebook, “My near death experience at Scarborough Shoal; Could’ve been the Sweetest Death.”

Kalayaan Atin Ito’s 2016 protest of China’s occupation of Scarborough was not official, but it had a maximum of heart and patriotism.

It was one way in which the Philippine people continued to demonstrate non-acquiescence to China’s claim and aggressions, and to show the Philippine government that they demand continued assertive measures to maintain Philippine sovereignty, an independent foreign policy, and the territorial integrity of the Philippines.

Official non-acquiescence is critical to the maintenance of the Philippines’ claims to sovereignty over Scarborough, and the rest of the Philippines’ territory and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) within China’s nine-dash line.

A Chinese protester throws eggs at photos of US President Barack Obama and torn copies of the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague against Beijing’s extensive claims in the South China Sea, outside Hong Kong’s United States Consulate on July 14, 2016. About 50 pro-China activists marched to Hong Kong’s United States Consulate holding placards that read ‘Ruling is a piece of paper’, ‘US sowing discord and stirring up trouble’, as they shouted slogans such as ‘No Compromise on South China Sea’ and ‘Shameless US’. The protesters also threw eggs on pieces of paper placed on the ground — featuring the picture of US President Barack Obama — outside the consulate.

According to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)

Award in the Philippines v. China case, “In practice, to establish the exclusive historic right to living and non-living resources within the ‘nine-dash line’, which China now appears to claim, it would be necessary to show that China had historically sought to prohibit or restrict the exploitation of such resources by the nationals of other States and that those States had acquiesced in such restrictions.”

International lawyers will argue that China’s actions over the last 20 years, now that the dispute has started, will not adversely affect the Philippine sovereignty claim.

But China is progressively destroying the shoal, and to be on the safe side of the sovereignty issue, and increase political as well as legal pressure, I think it critical to physically demonstrate regular official as well as popular non-acquiescence to China’s claim.

It is a political as well as legal issue, so the duty to defend the sovereign territorial rights of the Philippine nation requires frequent public demonstration.

The shoal is a high-tide feature according to the PCA’s 2016 interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (

UNCLOS).

Scarborough is therefore vulnerable to being claimed as territory by China, along with a 12 nautical mile (nm) territorial sea and rights to build or fish there as China would were it sovereign territory.

“Whichever state has title to Scarborough shoal is entitled to a 12 nm territorial sea,” according to James Kraska, Professor of Law at the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College.

For hundreds of years, Philippine sovereignty and traditional fishing methods at Scarborough Shoal protected it from overfishing.

The first historical depiction of Scarborough Shoal was on a

1734 map of the Philippines drawn in Manila during the Spanish colonial era.

In

1953, the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries published a book that discussed Scarborough Shoal as historically one of the “principal fishing areas” of Filipino fishermen.

In

1965, the Philippine Navy erected an iron tower on the site.

The Philippines presented affidavits of fishermen to the PCA that showed indirect evidence of Philippine fishing at Scarborough as early as 1972, and direct evidence of fishing since 1982.

Filipino fishermen on a small fishing boat on July 10, 2016 in Mariveles, Bataan, Philippines. Filipino fishermen regularly set sail into the South China Sea while claiming rights to the disputed waters between China and the Philippines. Tony Fernandez, a fisherman who has frequented the South China Sea for nearly 30 years says, ‘we’ve been fishing in these waters within our territories for decades, we know what is ours and not.’

China’s claims to Scarborough are much later, and do not include detailed evidence of fishing.

They stem from an official

1948 map titled “Map Showing the Location of the Various Islands in the South Sea” of an 11-dash line that surrounds the entire South China Sea, including a depiction of Scarborough.

In

1997, China erected a flag on the shoal, which was taken down by Filipino fishermen who erected their own flag.

In

1998 and 1999, the Philippines arrested dozens of Chinese fishermen on multiple occasions after gathering endangered corals and sea turtles.

They were in possession of blast fishing equipment, like dynamite and detonation cords.

Between 2000 and 2001, the Philippine Navy attempted to scare off Chinese fishermen from Scarborough, including with live fire, but did not arrest them.

After the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) was signed in 2002, disputes at Scarborough decreased.

Since 2009, China turbo-charged its sovereignty claims to the entire South China Sea, including Scarborough Shoal, by sending a map of a new 9-dash line (minus two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin removed in 1953) in an official communication to the United Nations and more aggressively “policing” the area with its coast guard and armed fishing boats called a “maritime militia”.In 2012, the Philippines Coast Guard once again responded to reports of

Chinese destructive fishing methods at Scarborough, including fishing of endangered coral, sea turtles, and live sharks.

But this time something changed.

China placed two

maritime surveillance ships between the Philippine Coast Guard and Chinese fishermen, then

strung 28 utility boats together to block Philippine fishermen and Coast Guard from entering the shoal. Chinese fishermen unload the last of their catch for the season as fishing boats arrive back in Qionghai, south China’s Hainan province on May 16, 2012.

Chinese fishermen unload the last of their catch for the season as fishing boats arrive back in Qionghai, south China’s Hainan province on May 16, 2012.

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State

Kurt Campbell brokered a deal whereby the Philippine Coast Guard and fishermen left the shoal to end the standoff.

China said they would leave but reneged.

China stayed in the vicinity of the shoal, and continued blocking Filipinos from fishing there, including with

water cannon.

The Philippine Navy and Coast Guard did not return.

This affirmed a Chinese strategy of incrementalist salami-slicing tactics by which China could gain territory without ever fighting.

Chinese analysts called it the “Scarborough Model.”

Due to a Chinese promise of $24 billion in funding and investment commitments to the Philippines, and President Rodrigo Duterte’s thawing of relations, China allowed some Filipino fishermen to return this year.

But according to this week’s Reuters

reports, very small numbers of Philippine fishermen have been allowed to return, and they can only take small boats into the interior lagoon of the shoal.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry confirmed Tuesday that China Coast Guard at Scarborough Shoal are there administering fishing activities of Filipino fishermen.China’s administration of Scarborough Shoal is in direct violation of Philippine sovereignty of the feature.

“The Philippines has sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal,” said Kraska in an email.

“Territorial title to the feature inured to the Philippines through extensive Spanish possession. Philippine title to Scarborough Shoal was recognized by the United States, which used the feature as a bombing range for US forces based in the Philippines.”

Environmental destruction by Chinese industrial fishing at Scarborough Shoal is the product of a lack of enforced Philippine sovereignty.

“This is a common problem in the law of the sea and international law more generally – it is a collective action problem in that all states would benefit from a solution that restrains China, but no state wants to bear the cost of trying to achieve that goal,” said Kraska.

Philippine protesters wearing cut-out turtle shells hold placards during an anti-China protest in front of the Chinese consulate in the financial district of Manila on May 16, 2014. Several hundred Filipino and Vietnamese protesters united in a march in the Philippine capital, demanding that China stop oil drilling in disputed South China Sea waters.

Philippine protesters wearing cut-out turtle shells hold placards during an anti-China protest in front of the Chinese consulate in the financial district of Manila on May 16, 2014. Several hundred Filipino and Vietnamese protesters united in a march in the Philippine capital, demanding that China stop oil drilling in disputed South China Sea waters.

Lack of enforcement of Philippine sovereignty at Scarborough is now a tragedy for an astonishing range of issues.

In addition to obvious negative effects on the environment, Philippine fishing families, and the sovereign territorial integrity of the Philippines and its EEZ, it is a tragedy for three policy areas that make this personal.

First, lack of stronger U.S. action at Scarborough has weakened the U.S.-Philippine alliance by making the U.S. commitment to the Philippines appear less credible.

Second, the ability of China to increasingly occupy the South China Sea without being held accountable, including at Scarborough Shoal since 2012, has strengthened and emboldened it generally.

Given that China is the world’s most powerful authoritarian regime, its increasing lack of international legal accountability is a threat to democracy in not only Asia, but beyond.

If China continues to increase its authoritarian reach, that could eventually affect not only the Philippines, but the children and grandchildren of Americans.

Some would say it already has.

Third, the fact that the Philippines has no independent legal recourse to address the sovereignty issues of China’s occupation of Scarborough Shoal demonstrates the general weakness of international law, and its lack of enforcement.

A stronger international legal regime would allow the Philippines to take China to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on a sovereignty dispute, even without China’s consent.

That is not currently possible, which is a weakness of international law on sovereignty issues that nation states should rectify.

That weakness means that sovereignty issues, if one party is not amenable to peaceful arbitration, must be resolved through force or the threat of force, such as

economic sanctions or

naval blockades. That increases international instability, and is an increasingly dangerous anarchic international situation as military technologies, including nuclear weapons, proliferate and become more powerful.

Scarborough Shoal is therefore much more important internationally than its strict legal designation of a “rock” would imply.

What happens, or is prevented from happening, at Scarborough will augur more of the same.

The critical issue at Scarborough is disputed sovereignty, which the PCA

Award last year did not and could not address.

According to the Award, “The [UNCLOS] Convention [] does not address the sovereignty of States over land territory. Accordingly, this Tribunal has not been asked to, and does not purport to, make any ruling as to which State enjoys sovereignty over any land territory in the South China Sea, in particular with respect to the disputes concerning sovereignty over the Spratly Islands or Scarborough Shoal. None of the Tribunal’s decisions in this Award are dependent on a finding of sovereignty, nor should anything in this Award be understood to imply a view with respect to questions of land sovereignty.”

The International Court of Justice.

The International Court of Justice.

Conversely, the ICJ is capable of arbitrating sovereignty disputes, and so could resolve the sovereignty issue at Scarborough Shoal.

“I firmly believe that in this day and age responsible states should take their sovereignty disputes to the International Court of Justice,” said Peter Dutton, Professor of Strategic Studies and Director of the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College.

But the ICJ can only arbitrate sovereignty disputes where both parties agree to submit the case.

“All options (like the ICJ) would require Chinese agreement,” said Greg Poling of the Center for Strategic and International and Studies.

“There is no such thing as compulsory dispute resolution for a sovereignty dispute.”

Because China is using its increasing military and economic advantages to gain territory in the South China Sea, East China Sea, and Himalayas, it is unlikely to set a precedent against itself by voluntarily agreeing to cede territory or go to the ICJ where those military and economic advantages have little to no effect.

“I don’t see much chance of anything bringing China around to ceding sovereignty or going to arbitration (which on Scarborough it would likely lose), at least not in any reasonable time frame,” said Poling in an email.

Some analysts, perhaps representing the mainstream of opinion in the U.S. given its inaction on Philippine sovereignty within its EEZ, think the U.S. should not take sides in sovereignty disputes between China and the Philippines.

“If either China or [t]he Philippines refuses to do so [arbitrate the Scarborough sovereignty disputes at the ICJ], the role of the international community is to support stability until such time as the parties can agree on how to resolve their dispute,” Dutton said by email.

“In my view it is not the role of the United States to champion the Philippine claim. Our role is to help maintain overall regional stability, not to provoke conflict by choosing a side.”

But there is no “stability” at Scarborough Shoal, and the theory of balancing in international relations tells us that not taking the side of the weaker party invites conflict.

Over 20 years, China has gradually removed most Filipino fishermen, destroyed the environmental habitat, and a Chinese military source and military experts have talked of plans to start building a military facility.Based on U.S. national interests alone, the U.S. and other allies should jointly pressure China into returning Scarborough to the status quo as it was in the mid-1990s.

Where some dispute exists on the nature of that status quo, we should use all means at our disposal, including economic sanctions and a robust naval presence at Scarborough, to pressure China into accepting arbitration by the ICJ.

Not doing so increases uncertainty about U.S. intentions in Asia, and thereby increases instability and the likelihood of war.

By not taking a stronger stand on Scarborough, Second Thomas Shoal, and Mischief Reef, for example, the U.S. actually fails to stop instability by allowing China to think that it can get away with occupying the entire South China Sea as its sovereign territory.

China’s continued incremental acquisitions of the South China Sea, to the extent allowed at places like Scarborough Shoal, will harm the national security of the U.S. by making China stronger and bolder.

Scarborough Shoal is just 250 km from Subic Bay, one of the most important naval bases in Asia, and one the U.S. historically utilized.

We could utilize it to a greater extent if we improved relations with the Philippines.

China’s building of a military base at Scarborough Shoal would make the value of Subic Bay as a naval base much less defensible.

This decreases the opportunities and relative power of the U.S., and increases those of China.

The U.S. has already taken sides.

In 1951 we signed the

Mutual Defense Treaty, which requires the U.S. to defend the Philippines. According to Article IV of the treaty, “Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on either of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common dangers in accordance with its constitutional processes.”

China Coast Guard is armed at Scarborough Shoal.

According to the affidavit of

Jowe Legaspi, who fished at Scarborough since 1994, “In May or June 2014, they [the Chinese] harassed Filipino fishermen through water cannon, sound blare, and there were times that they have a gun when they came near us.”

I personally saw light cannon mounted on the two China Coast Guard cutters that harassed the Kalayaan Atin Ito activists at Scarborough last June.

This picture taken on May 13, 2014 from a Vietnamese coast guard ship shows two Chinese coast guard vessels sailling near the area of China’s oil drilling rig in disputed waters in the South China Sea. Vietnam experienced its worst anti-China unrest in decades following Beijing’s deployment of an oil rig to disputed waters, with at least one Chinese worker killed and more than 100 injured.

This picture taken on May 13, 2014 from a Vietnamese coast guard ship shows two Chinese coast guard vessels sailling near the area of China’s oil drilling rig in disputed waters in the South China Sea. Vietnam experienced its worst anti-China unrest in decades following Beijing’s deployment of an oil rig to disputed waters, with at least one Chinese worker killed and more than 100 injured.

These armed Chinese acts, combined with Chinese occupation of the sovereign territory of the Philippines, arguably combine to constitute an “armed attack”.

The treaty further says, “For the purpose of Article IV, an armed attack on either of the Parties is deemed to include an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of either of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific or on its armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific.”

Last year, the PCA found Scarborough Shoal to be a “rock”, which is a legal subcategory of an “island” according to UNCLOS.

So the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty appears to apply to Scarborough.

Any attempt to further split legal hairs on the wording of the treaty and its relevance to Scarborough would not reflect well on American defense commitments.

The appearance of avoiding or reneging on a U.S. treaty commitment to protect Philippine territory in the South China Sea, including Scarborough Shoal, could make the U.S. look weak as an ally, not only to Filipinos, but to the world.

Ukraine already blames the U.S., rightly or wrongly, for not sufficiently fulfilling security guarantees in the Budapest Agreement of 1994, when Russia invaded Crimea.

Adding a failure to protect the Philippines from China could further tarnish our reputation.

The longer that China is allowed to administer Scarborough Shoal with the China Coast Guard, the more China, and international lawyers, will start to see it as China’s de facto sovereign territory.

And, possession is 9/10 of the law.

Some international lawyers already think China has the right to act as a sovereign at Scarborough.

“I think China is acting as sovereign — as it has a right to do — when it fishes in and around Scarborough Shoal,” said Dutton.

“I agree it is not engaging in artisanal fishing when it uses industrial sized vessels. But a sovereign has an unfettered right to choose how to fish in its own territorial sea and internal waters. The [PCA] arbitral opinion merely acknowledged that China and the Philippines (and others) have artisanal fishing rights at Scarborough without limiting other rights that might pertain to the sovereign. So I do not conclude China is acting unlawfully.”

Dutton’s assumption that China has a right to act as a sovereign at Scarborough Shoal is a stretch, and likely rejected by other international law scholars.

The Philippines has also

alleged that

China’s destruction of coral at Scarborough Shoal violates several international conventions to which China is a signatory, including the RAMSAR Convention (1971), the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1975), and the Convention on Biological Diversity (1993).While some lawyers may be able to justify China’s industrial fishing at Scarborough based on a hypothetical sovereignty, combined with one interpretation of international law,

China’s destruction of the environment in what most people think is the EEZ of another country is a dangerous precedent, and flies in the face of common sense values.Those common sense values that indicate the Philippines should have sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal start with Scarborough being much closer to the Philippines than to China.

Just look at a map.

Any reasonable person would say that China should not be “administering” Filipino fishermen at their own shoal.

Second, Scarborough is within the Philippine EEZ.

Scarborough at high tide is a small collection of rocks, the largest of which is not much bigger than a car.

This should not give China the right to claim it as territory, along with a 12 nm radius of territorial sea.

Third, when the Philippines administered Scarborough up to 2012, the shoal was for the most part sustainably fished by Filipino fishermen.

Now it is being destroyed by China, which has acted aggressively against Filipino fishermen.

China is likely seeking to build a military base at the shoal that will increase regional instability.

Fourth, the Philippine maps of Scarborough predate by centuries the Chinese maps that purportedly claim the shoal, and Philippine fishing at Scarborough predates China’s territorial claim.

Fifth, China likely refuses to arbitrate the sovereignty dispute at the ICJ, which would place China and its actions squarely outside the international rule of law.

Activists dressed as clowns and holding water pistols spray a map illustrating China’s claim to the South China Sea during a protest in front of the Chinese consular office in the financial district of Manila on March 3, 2014. Activists protested against Chinese ships firing a water cannon at Philippine fishermen.

Activists dressed as clowns and holding water pistols spray a map illustrating China’s claim to the South China Sea during a protest in front of the Chinese consular office in the financial district of Manila on March 3, 2014. Activists protested against Chinese ships firing a water cannon at Philippine fishermen.

Scarborough Shoal is 864 km from the Chinese coast, and only 223 km from the Philippines.

It is within the Philippines’ EEZ, which according to the basic UNCLOS rule, extends 200 nm (370km) from its coastline.

The Philippines has for a long time used the shoal as a primary location for fishing.

Only in very recent history has China increased its claims and activities at the shoal.

China refused to participate in the PCA arbitration, but in its absence the arbitral panel made an effort to collect evidence that supported China’s case.

In the award, the PCA referenced China’s embassy in Manila, which chose

June 12, 2012, Philippine Independence Day, to publish historical evidence for its claim to Scarborough.

“Scarborough Shoal and its surrounding waters have been China’s traditional fishing grounds since ancient times. Chinese fishermen have engaged in fishery activities for generations. In addition, they have used Scarborough Shoal as a safe have[n] in their voyage in the South China Sea. Genglubu, an ancient Chinese navigation log recording trips in the South China Sea, and other ancient documents and literature contain complete records of Chinese fishermen’s activities around Scarborough Shoal. Since the Yuan Dynasty, the Chinese people have never stopped developing and exploiting Scarborough Shoal and its surrounding waters and the Chinese government has exercised effective management and jurisdiction over their activities all these years. These historical facts are supported by official documents, local chronicles and official maps in the past centuries.”

These Chinese claims of evidence have no specific references or quotes, which puts into question the extent to which they actually show Chinese fishermen’s utilization of Scarborough Shoal.

In contrast, the Philippines presented a detailed case of its traditional fishing at Scarborough Shoal, which I presented above.

The family-owned Philippine fishing boats that have historically plied the waters of Scarborough Shoal are typically much smaller, for example about 30 meters, when compared to the 75-meter Chinese industrial fishing trawlers documented by Reuters at Scarborough on Monday.

Some of the Philippine boats at Scarborough are “barely more than rafts,” according to the

article. These artisanal fishermen come from family fishing communities in nearby Philippine towns such as Masinloc, Palauig, and Iba.

Their artisanal spear, line and small-net fishing will not be protected if China is allowed to administer the shoal, and facilitate industrial fishing that progressively denudes the shoal’s fish, coral, giant clams, and sea turtles, many of which are endangered.

The ecosystem at Scarborough is already critically damaged, but continued Chinese industrial fishing at the location will sever a critical link in migratory fish movements around the South China Sea. “Chinese overfishing and, even more damaging, it’s previous reef destruction to poach giant clams, has done horrendous damage to the marine ecosystem at Scarborough,” said Poling.

“Filipino fishermen report significantly reduced catches, and there’s no telling how bad things will get. It’s entirely possible that so much damage has been done to reef ecosystems in Scarborough and the Spratlys that we’ll soon see a collapse of migratory fish stocks throughout the South China Sea.”

Giant clams flourish on the sea bed off Bolinao in Lingayen Gulf, northwest of Manila on October 18, 2008. Highly prized for its meat and decorative shell the giant clam, scientific name: Tridacna gigas had virtually disappeared from the Philippines fished out by local and foreign fishermen. Marine biologists from the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines launch in 1985 an ambitious programme to breed and restock the waters in this south east Asian archipelago of 7,000 islands. Giant clams form an integral part of a coral reef’s ecosystem. A large clam can weigh up to 230 kilos.

Giant clams flourish on the sea bed off Bolinao in Lingayen Gulf, northwest of Manila on October 18, 2008. Highly prized for its meat and decorative shell the giant clam, scientific name: Tridacna gigas had virtually disappeared from the Philippines fished out by local and foreign fishermen. Marine biologists from the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines launch in 1985 an ambitious programme to breed and restock the waters in this south east Asian archipelago of 7,000 islands. Giant clams form an integral part of a coral reef’s ecosystem. A large clam can weigh up to 230 kilos.

Based on the common sense values above, the Philippines and its allies are arguably not only justified, but legally obligated, to actively defend Philippine sovereignty, territory and the environment at Scarborough.

To do so, the Philippines should continuously object to China’s occupation.

“The best Manila can do is continuously object and refuse to recognize Chinese sovereignty, in order to maintain a clear legal record of its objections,” said Poling.

“The Philippines has effectively used law to chasten China, and should continue to do so,” said Kraska.

“It might, for example, encourage Vietnam to file a similar suit. Also, the Philippines should try to obtain multilateral lateral agreement on the SCS with the other claimants to further isolate China and attract greater international support.”

These are important legal measures to take.

But China has shown its disregard for international law by

refusing to participate in, or accept the findings of, the Philippines v. China case at the PCA.

Therefore stronger measures are required.

Economic sanctions against China and joint U.S.-Philippine Coast Guard and Navy patrols at Scarborough should be utilized to enforce China’s agreement to arbitrate the sovereignty issue at the ICJ, and in the interim block Chinese activities at the shoal, including industrial fishing, pretensions of providing governance through coast guard operations, and military base construction.

The same tactics should be employed to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Philippines in the rest of its EEZ, for example at Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal.

To decrease the likelihood of joint U.S.-Philippine enforcement erupting into conflict with China, take a leaf from the Chinese strategy book: implement enforcement gradually.

If the Philippine and U.S. governments do not take more assertive measures to oppose China’s occupation of Scarborough Shoal, and reaffirm and enforce Philippine sovereignty, they are not sufficiently doing their jobs and are possibly breaking the law.

In this case the Philippine and American people, and their respective congressional representatives, would be well-advised to encourage stronger executive action through legal activism and new legislation that mandates the enforcement of Philippine sovereignty over its territory.

A protester holds a sign saying ‘Benham Rise is Philippine territory!’ in front of the Chinese Consulate to protest Duterte’s perceived closeness to China and China’s continuing ‘militarization’ of the disputed islands in the South China Sea, on March 24, 2017 in the financial district of Makati, Philippines. The protesters accused President Rodrigo Duterte of siding with China instead of the Filipino people and are protesting against alleged plans to build military structures on Scarborough Shoal as well as months of alleged incursions of Chinese research vessels in the Benham Rise, east of the country.

Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said he expects ASEAN to further debate in the coming months the need for a 'Code of Conduct' with China over the South China Sea issue

Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said he expects ASEAN to further debate in the coming months the need for a 'Code of Conduct' with China over the South China Sea issue