Al Jazeera

For decades, a Uighur imam was a bedrock of his farming community in China's far west.

For decades, a Uighur imam was a bedrock of his farming community in China's far west.

On Fridays, he preached Islam as a religion of peace.

On Sundays, he treated the sick with free herbal medicine.

In the winter, he bought coal for the poor.

But as a Chinese government mass detention campaign engulfed Memtimin Emer's native East Turkestan colony three years ago, the elderly imam was swept up and locked away, along with all three of his sons living in China.

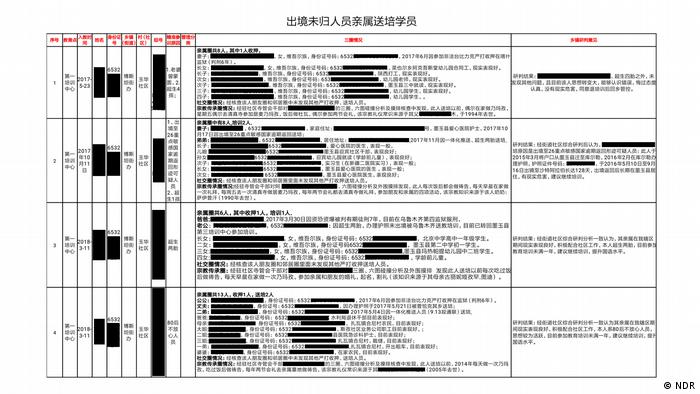

Now, a newly revealed database exposes in extraordinary detail the main reasons for the detentions of Emer, his three sons, and hundreds of others in Karakax County: their religion and their family ties.

The database obtained by The Associated Press news agency profiles the internment of 311 individuals with relatives abroad and contains information on more than 2,000 of their relatives, neighbours and friends.

Each entry includes the detainee's name, address, national identity number, detention date and location, along with a detailed dossier on their family, religious and neighbourhood background, the reason for the detention and a decision on whether or not to release them.

Issued within the past year, the documents do not indicate which government department compiled them or for whom.

Taken as a whole, the information offers the fullest and most personal view yet into how Chinese officials picked who was put into and who was let out of concentration camps, as part of a significant crackdown that has locked away more than a million ethnic minorities, most of them Muslims.

The database emphasises that the Chinese government focused on religion as a reason for detention -- not just political violence, as authorities claim, but everyday activities such as praying, attending a mosque, or even growing a long beard.

Religious practice targeted

It also shows the role of family: People with detained relatives are far more likely to end up in a camp themselves, uprooting and giving entire families like Emer's a criminal record in the process.

Similarly, family background and attitude is a bigger factor than detainee behaviour in whether they are released.

"It's very clear that religious practice is being targeted," said Darren Byler, a University of Colorado researcher studying the use of surveillance technology in East Turkestan.

"They want to fragment society, to pull the families apart and make them much more vulnerable to retraining and re-education."

The East Turkestan colonial government did not respond to faxes requesting comment.

'Witch-hunt mindset'

Detainees and their families are tracked and classified by rigid, well-defined categories.

Renowned teacher

Even in Karakax county, famed for its intellectuals and scholars, Emer stood out as one of the most renowned teachers in the region.

Muhammad studied the Quran under Emer for six years as a kid, following him from house to house in an effort to dodge the authorities.

Muhammad said Emer was so respected that the police would phone him with warnings ahead of time before raiding classes at his modest, single-story home of brick and mud.

Under heavy surveillance

Though Emer gave Party-approved sermons, he refused to preach Communist propaganda, Muhammad said, eventually running into trouble with the authorities.

'He never bowed down to them'

It also shows that their relation to Emer and their religious background was enough to convince officials they were too dangerous to let out from the concentration camps."His father taught him how to pray," notes one entry for his eldest, Ablikim Memtimin.

"His family's religious atmosphere is thick. We recommend he (Emer) continue training," says another entry for his youngest son, Emer Memtimin.

Even a neighbour was tainted by living near him with Emer's alleged crimes and prison sentence recorded in the neighbour's dossier.

The database indicates much of this information is collected by teams of cadres stationed at mosques, sent to visit homes and posted in communities.

But as a Chinese government mass detention campaign engulfed Memtimin Emer's native East Turkestan colony three years ago, the elderly imam was swept up and locked away, along with all three of his sons living in China.

Now, a newly revealed database exposes in extraordinary detail the main reasons for the detentions of Emer, his three sons, and hundreds of others in Karakax County: their religion and their family ties.

The database obtained by The Associated Press news agency profiles the internment of 311 individuals with relatives abroad and contains information on more than 2,000 of their relatives, neighbours and friends.

Each entry includes the detainee's name, address, national identity number, detention date and location, along with a detailed dossier on their family, religious and neighbourhood background, the reason for the detention and a decision on whether or not to release them.

Issued within the past year, the documents do not indicate which government department compiled them or for whom.

Taken as a whole, the information offers the fullest and most personal view yet into how Chinese officials picked who was put into and who was let out of concentration camps, as part of a significant crackdown that has locked away more than a million ethnic minorities, most of them Muslims.

The database emphasises that the Chinese government focused on religion as a reason for detention -- not just political violence, as authorities claim, but everyday activities such as praying, attending a mosque, or even growing a long beard.

Religious practice targeted

It also shows the role of family: People with detained relatives are far more likely to end up in a camp themselves, uprooting and giving entire families like Emer's a criminal record in the process.

Similarly, family background and attitude is a bigger factor than detainee behaviour in whether they are released.

"It's very clear that religious practice is being targeted," said Darren Byler, a University of Colorado researcher studying the use of surveillance technology in East Turkestan.

"They want to fragment society, to pull the families apart and make them much more vulnerable to retraining and re-education."

The East Turkestan colonial government did not respond to faxes requesting comment.

Heavy-handed rule

China has struggled for decades to control East Turkestan, where the native Uighurs have long resented Beijing's heavy-handed rule.

With the 9/11 attacks in the United States, officials began using the spectre of "terrorism" to justify harsher religious restrictions, saying young Uighurs were susceptible to violence "extremism".

After armed groups set off bombs at a train station in East Turkestan's capital in 2014, Xi Jinping launched a so-called "People's War on Terror", transforming East Turkestan into a digital police state.

The leak of the database from sources in the Uighur exile community follows the release in November of a classified blueprint on how the mass detention system really works.

Uighur women use carts to transport cement for home renovations at the Unity New Village in Hotan, in western China's East Turkestan colony in 2018.

The blueprint obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which includes the AP, showed that the centres are in fact forced ideological and behavioural re-education camps run in secret.

Another set of documents leaked to the New York Times newspaper revealed the historical lead-up to the mass detention.

The latest set of documents came from sources in the Uighur exile community, dating most recently to March 2019.

The detainees listed come from Karakax County, a traditional settlement of about 650,000 on the edge of East Turkestan's Taklamakan Desert where more than 97 percent of residents are Uighur.

The list was corroborated through interviews with former Karakax residents, Chinese identity verification tools and other lists and documents seen by the AP.

After armed groups set off bombs at a train station in East Turkestan's capital in 2014, Xi Jinping launched a so-called "People's War on Terror", transforming East Turkestan into a digital police state.

The leak of the database from sources in the Uighur exile community follows the release in November of a classified blueprint on how the mass detention system really works.

Uighur women use carts to transport cement for home renovations at the Unity New Village in Hotan, in western China's East Turkestan colony in 2018.

The blueprint obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which includes the AP, showed that the centres are in fact forced ideological and behavioural re-education camps run in secret.

Another set of documents leaked to the New York Times newspaper revealed the historical lead-up to the mass detention.

The latest set of documents came from sources in the Uighur exile community, dating most recently to March 2019.

The detainees listed come from Karakax County, a traditional settlement of about 650,000 on the edge of East Turkestan's Taklamakan Desert where more than 97 percent of residents are Uighur.

The list was corroborated through interviews with former Karakax residents, Chinese identity verification tools and other lists and documents seen by the AP.

'Witch-hunt mindset'

Detainees and their families are tracked and classified by rigid, well-defined categories.

Households are designated as "trustworthy" or "not trustworthy" and their attitudes are graded as "ordinary" or "good."

Families have "light" or "heavy" religious atmospheres and the database keeps count of how many relatives of each detainee are locked in prison or sent to a "training centre."

Officials used these categories to determine how suspicious a person was -- even if they had not committed any crimes.

"It underscores the witch-hunt mindset of the government and how the government criminalises everything," said Adrian Zenz, an expert on the detention centres and senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, DC.

Reasons listed for internment include "minor religious infection," "disturbs other persons by visiting them without reasons," "relatives abroad," "thinking is hard to grasp" and "untrustworthy person born in a certain decade."

Officials used these categories to determine how suspicious a person was -- even if they had not committed any crimes.

"It underscores the witch-hunt mindset of the government and how the government criminalises everything," said Adrian Zenz, an expert on the detention centres and senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, DC.

Reasons listed for internment include "minor religious infection," "disturbs other persons by visiting them without reasons," "relatives abroad," "thinking is hard to grasp" and "untrustworthy person born in a certain decade."

The last seems to refer to younger men; about 31 percent of people considered "untrustworthy" were in the age bracket of 25 to 29 years, according to an analysis of the data by Zenz.

When former student Abdullah Muhammad spotted Emer's name on the list of the imprisoned, he was distraught.

"He didn't deserve this," Muhammad said.

When former student Abdullah Muhammad spotted Emer's name on the list of the imprisoned, he was distraught.

"He didn't deserve this," Muhammad said.

"Everyone liked and respected him. He was the kind of person who couldn't stay silent against injustice."

Renowned teacher

Even in Karakax county, famed for its intellectuals and scholars, Emer stood out as one of the most renowned teachers in the region.

Muhammad studied the Quran under Emer for six years as a kid, following him from house to house in an effort to dodge the authorities.

Muhammad said Emer was so respected that the police would phone him with warnings ahead of time before raiding classes at his modest, single-story home of brick and mud.

Under heavy surveillance

Though Emer gave Party-approved sermons, he refused to preach Communist propaganda, Muhammad said, eventually running into trouble with the authorities.

He was stripped of his position as an imam and barred from teaching in 1997 amid unrest roiling the region.

When Muhammad left China for Saudi Arabia and Turkey in 2009, Emer was making his living as a doctor of traditional medicine.

When Muhammad left China for Saudi Arabia and Turkey in 2009, Emer was making his living as a doctor of traditional medicine.

Emer was growing old and under heavy surveillance, he had stopped attending religious gatherings.

That did not stop authorities from detaining the imam, who is in his eighties and sentencing him on various charges for up to 12 years in prison over 2017 and 2018.

The database cites four charges in various entries: "stirring up terrorism," acting as an unauthorised "wild" imam, following the strict Saudi Wahhabi sect and conducting illegal religious teachings.

Muhammad called the charges false.

That did not stop authorities from detaining the imam, who is in his eighties and sentencing him on various charges for up to 12 years in prison over 2017 and 2018.

The database cites four charges in various entries: "stirring up terrorism," acting as an unauthorised "wild" imam, following the strict Saudi Wahhabi sect and conducting illegal religious teachings.

Muhammad called the charges false.

Emer had stopped his preaching, practised a moderate Central Asian sect of Islam rather than Wahhabism and had never dreamed of hurting others, let alone stirring up "terrorism," Muhammad said.

"He used to always preach against violence," Muhammad said.

"He used to always preach against violence," Muhammad said.

"Anyone who knew him can testify that he wasn't a religious extremist."

None of Emer's three sons had been convicted of a crime.

None of Emer's three sons had been convicted of a crime.

But the database shows that over the course of 2017, all were thrown into the detention camps for having too many children, trying to travel abroad, being "untrustworthy" or "infected with religious extremism," or going on the Hajj, the Muslim pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca.

'He never bowed down to them'

It also shows that their relation to Emer and their religious background was enough to convince officials they were too dangerous to let out from the concentration camps."His father taught him how to pray," notes one entry for his eldest, Ablikim Memtimin.

"His family's religious atmosphere is thick. We recommend he (Emer) continue training," says another entry for his youngest son, Emer Memtimin.

Even a neighbour was tainted by living near him with Emer's alleged crimes and prison sentence recorded in the neighbour's dossier.

The database indicates much of this information is collected by teams of cadres stationed at mosques, sent to visit homes and posted in communities.

This information is then compiled in a dossier called the "three circles", encompassing their relatives, community, and religious background.

It was not just the religious who were detained.

It was not just the religious who were detained.

The database shows that Karakax officials also explicitly targeted people for activities that included going abroad, getting a passport or installing foreign software.

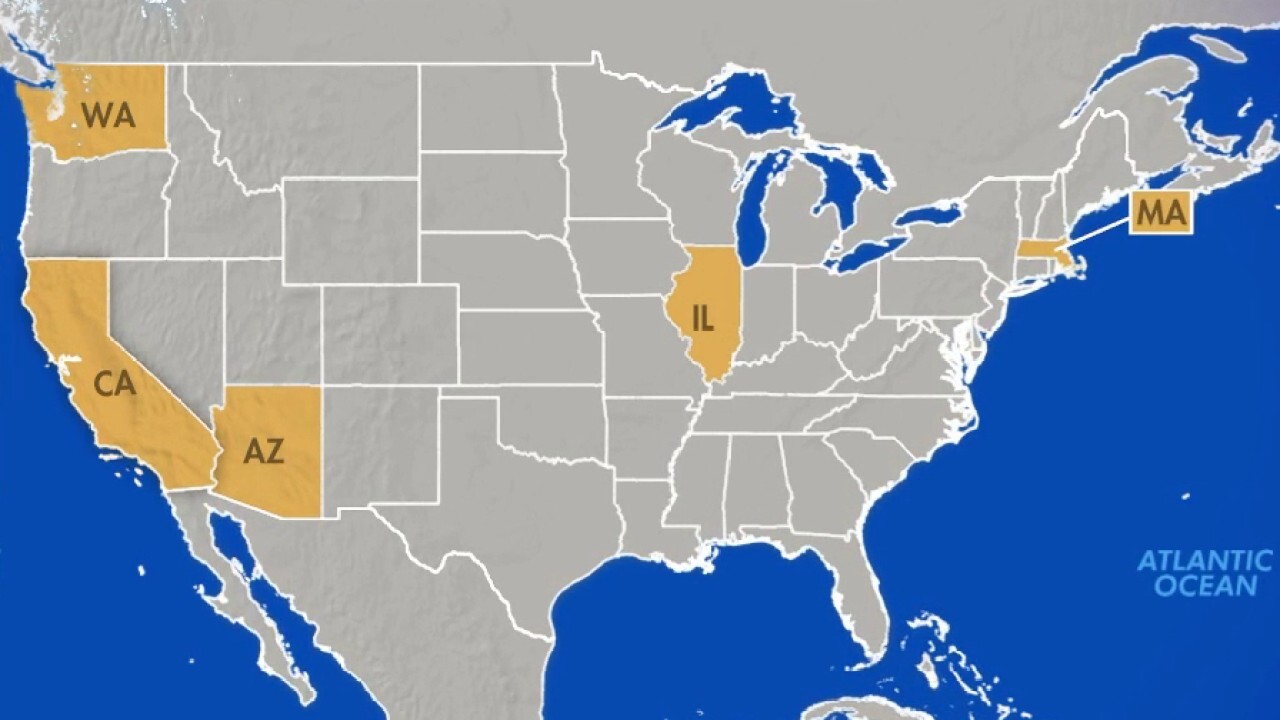

Pharmacist Tohti Himit was detained in a camp for having gone multiple times to one of 26 "key" countries, mostly Muslim, according to the database.

Pharmacist Tohti Himit was detained in a camp for having gone multiple times to one of 26 "key" countries, mostly Muslim, according to the database.

Former employee Habibullah, who is now in Turkey, recalled Himit as a secular, kind and wealthy man who kept his face free of a beard.

"He wasn't very pious, he didn't go to the mosque," said Habibullah, who declined to give his first name out of fear of retribution against family still in China.

"He wasn't very pious, he didn't go to the mosque," said Habibullah, who declined to give his first name out of fear of retribution against family still in China.

"I was shocked by how absurd the reasons for detention were."

The database says cadres found Himit had attended his grandfather's funeral at a local mosque on March 10, 2008.

The database says cadres found Himit had attended his grandfather's funeral at a local mosque on March 10, 2008.

Later that year, the cadres found, he had gone to the same mosque again, once to worship and once to celebrate a festival.

In 2014 he had gone to Anhui province, in inner China, to get a passport and go abroad.

That, the government concluded, was enough to show that Himit was "certainly dangerous."

That, the government concluded, was enough to show that Himit was "certainly dangerous."

They ordered Himit to stay in the centre and "continue training."

Emer is now under house arrest due to health issues, his former student, Muhammad, has heard.

Emer is now under house arrest due to health issues, his former student, Muhammad, has heard.

It is unclear where Emer's sons are.

It was the imam's courage and stubbornness that did him in, Muhammad said.

It was the imam's courage and stubbornness that did him in, Muhammad said.

Though deprived of his mosque and his right to teach, Emer quietly defied the authorities for two decades by staying true to his faith.

"Unlike some other scholars, he never cared about money or anything else the Communist Party could give him," Muhammad said.

"Unlike some other scholars, he never cared about money or anything else the Communist Party could give him," Muhammad said.

"He never bowed down to them -- and that's why they wanted to eliminate him."

Muslim men of the Uighur ethnic group leaving the Id Kah Mosque after Friday prayers in Kashgar, East Turkestan

Muslim men of the Uighur ethnic group leaving the Id Kah Mosque after Friday prayers in Kashgar, East Turkestan

Workers walk by the perimeter fence of a concentration camp in Dabancheng in East Turkestan, China, on Sept. 4, 2018.

Workers walk by the perimeter fence of a concentration camp in Dabancheng in East Turkestan, China, on Sept. 4, 2018.

Ablet Abdugani with his daughter Serife, 15, and his sons Abdussalam, 11, and Abdullah, age 5, at their home in Istanbul, Turkey.

Ablet Abdugani with his daughter Serife, 15, and his sons Abdussalam, 11, and Abdullah, age 5, at their home in Istanbul, Turkey.

Hong Kong protesters held a rally in support of the Uighurs on Sunday.

Hong Kong protesters held a rally in support of the Uighurs on Sunday.