Universities can’t handle Confucius Institutes responsibly. The state should step in.

BY ANDREAS FULDA

The exasperated expression on the face of Tom Tugendhat, the chairman of the British Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, at a public hearing on the influence of autocracies on U.K. universities gave it away.

Tugendhat had just asked what could be done to address self-censorship among Chinese students in the United Kingdom or the United States.

The evasive answers by Alexander Bustamante, the senior vice president and chief compliance and audit officer at the University of California, and Bill Rammell, the vice chancellor at the University of Bedfordshire and chair of MillionPlus, the Association for Modern Universities, were met with a frown and the occasional glance at the chairman’s mobile phone.

Tugendhat, a former British Army officer and counterintelligence expert, was not having it.

Tugendhat is not the only exasperated one in this discussion.

Tugendhat is not the only exasperated one in this discussion.

Over the last 15 years, one question has come up again and again: the role of Confucius Institutes, funded and run by the Chinese party-state, in extending Chinese censorship to Western universities.

Since 2004, around 550 Confucius Institutes have opened worldwide, with close to 100 in the United States and 29 in the United Kingdom.

Since 2004, around 550 Confucius Institutes have opened worldwide, with close to 100 in the United States and 29 in the United Kingdom.

In recent years, however, the enthusiasm with which university leaders around the world have embraced the institutes has soured.

Increasing numbers of them have been shut.

That’s partially thanks to the geopolitical shift against an increasingly autocratic Chinese Communist Party (CCP) under Xi Jinping’s leadership and partially due to the institutes themselves being no more immune to the CCP’s waves of political repression than any other Chinese state institute—even abroad.

Confucius Institutes repeatedly stray from their publicly declared key task of providing Mandarin Chinese language training and venture into deep ideological territory.

Confucius Institutes repeatedly stray from their publicly declared key task of providing Mandarin Chinese language training and venture into deep ideological territory.

The institutes’ learning materials distort contemporary Chinese history and omit party-induced humanitarian catastrophes such as the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) entirely.

At Confucius Institute events, politically sensitive issues like Taiwan, Tibet, and Tiananmen cannot be publicly discussed either.

In 2014, a conference in Braga, Portugal, that involved both the Confucius Institute headquarters and the Taiwan-based Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange as co-sponsors was unceremoniously interrupted by Confucius Institute headquarters chief Xu Lin.

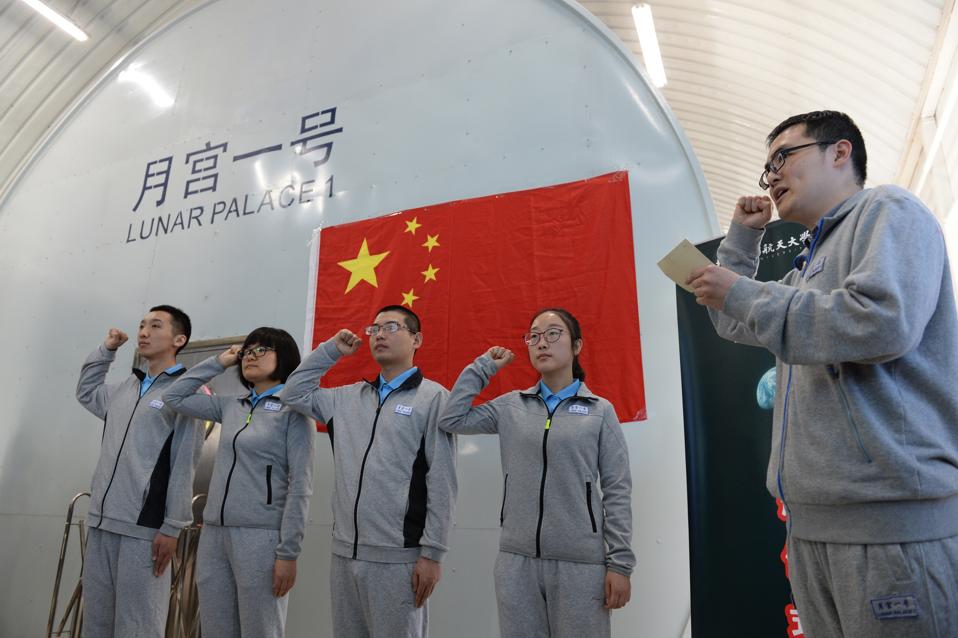

And under the conditions of the Seven Don’t Speak directive, mainland Chinese education workers are barred from talking about universal values, freedom of speech, civil society, civil rights, the historical errors of the CCP, official bourgeoisie, and judicial independence—even when overseas.

There is an existing problem of self-censorship among China scholars.

There is an existing problem of self-censorship among China scholars.

A recent survey revealed that in the face of increasing CCP censorship, “researchers employ several tactics in the face of such pressures. Almost half — some 48% — of respondents adapted how they describe their project in order to continue doing it, 25% changed the project’s focus, and 15% discontinued a project because of concern for sensitivity — or feasibility as the likelihood of being denied archive access in China made many projects unfeasible.”

Confucius Institutes bring another factor in: the hope of money and the fear of losing it.

In a report by the Royal United Services Institute on China-U.K. relations, Charles Parton, a former British diplomat and security expert, pointed out that the “problem does not lie primarily with teaching staff. Often, when they meet pressure, they are not backed up by university administrators.

A number of professors have told the author that vice-chancellors and other administrators have not supported them when they have been subject to pressures which impinge on academic freedom.”

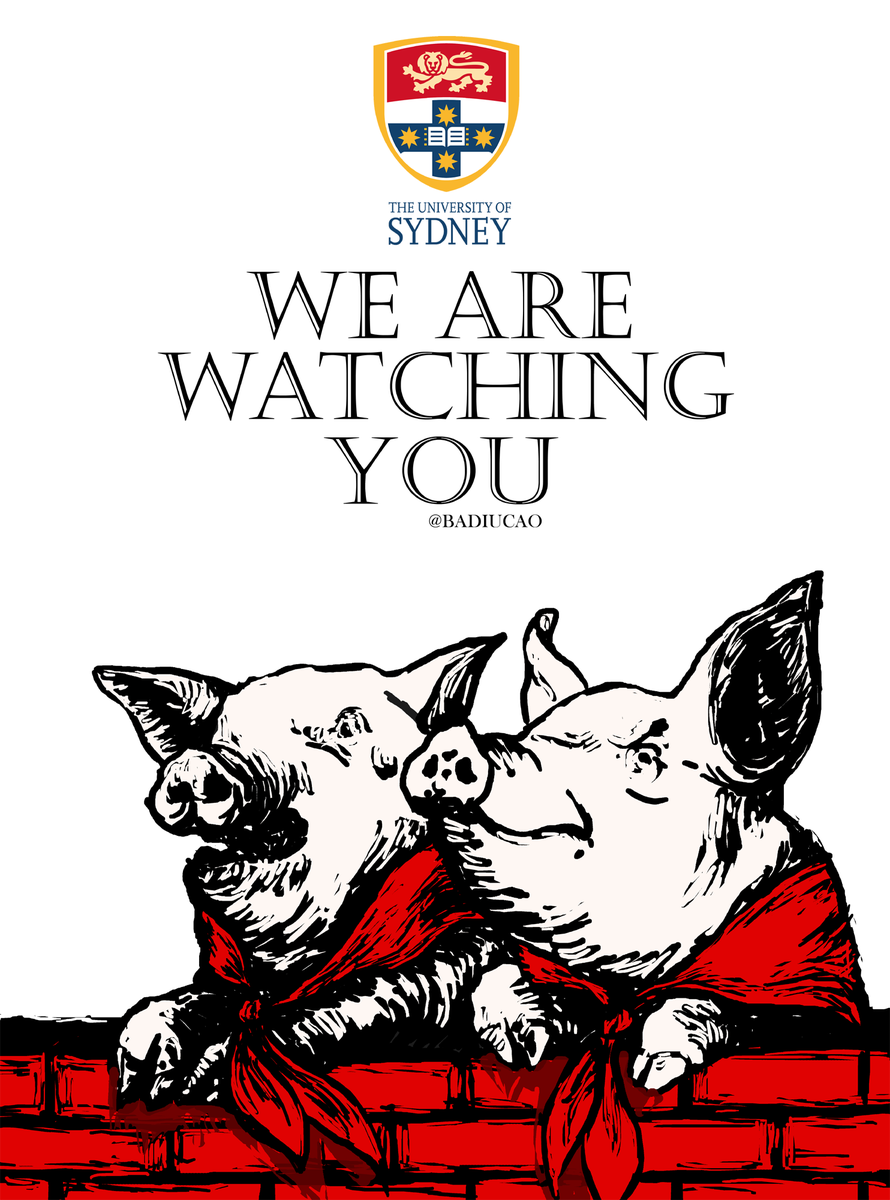

Confucius Institutes at universities can be likened to Perry Link’s “anaconda in the chandelier”—his metaphor for the power of censorship in China.

Confucius Institutes at universities can be likened to Perry Link’s “anaconda in the chandelier”—his metaphor for the power of censorship in China.

While the anaconda may not move, its shadow nevertheless induces fear among staff, students, and university managers alike, and they react accordingly.

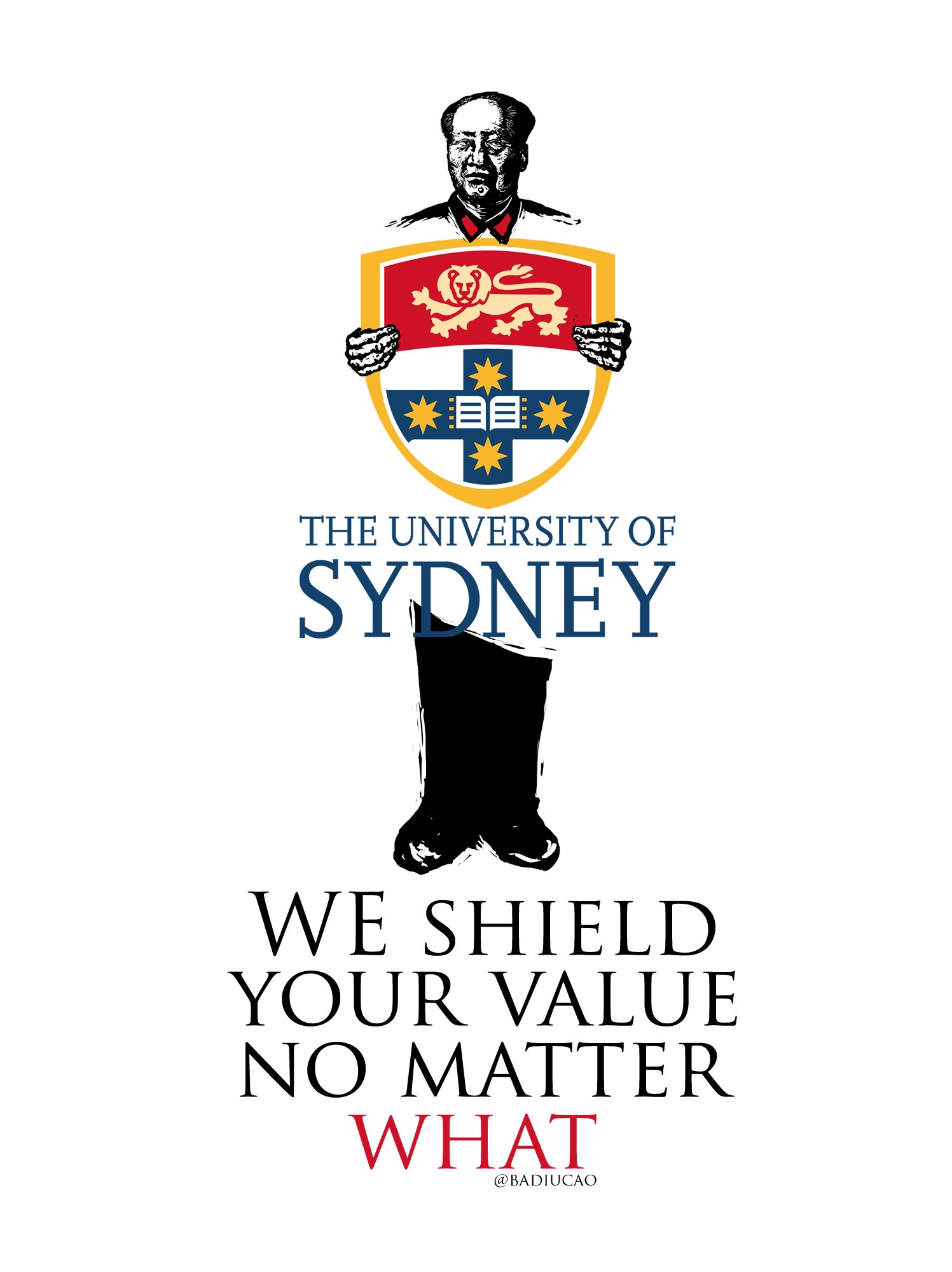

Mindful of the importance of international student recruitment, there is little appetite among university administrators to jeopardize the steady stream of fee-paying international students from mainland China.

Confucius Institutes play a double role: They are both cultural and political organizations.

Confucius Institutes play a double role: They are both cultural and political organizations.

When discussing the equally controversial role of Chinese Students and Scholars Associations, student groups with strong ties to the Chinese embassies, the British academic Martin Thorley recently coined the term “latent network.”

In Thorley’s words, the “latent network is one of multiple forms of power transmission by the Party-state over the periphery. The firewall between the public and the private, typically a far more robust fixture in liberal democracies, must be more permeable in a system where a single institution rules without effective legal oversight.”

Thorley goes on to explain that “institutions within this network, though not necessarily controlled by the CCP directly in their day-to-day affairs, are dependent on CCP patronage and thus, subject to CCP direction.”

The fate of the Lyon Confucius Institute (LCI) underscores the danger that Confucius Institutes as latent networks pose.

The fate of the Lyon Confucius Institute (LCI) underscores the danger that Confucius Institutes as latent networks pose.

Following the arrival of an activist director from mainland China in the fall of 2012, an increasingly bitter conflict ensued over curriculum development.

When LCI Chair of the Board Gregory Lee successfully resisted such attempts to introduce a CCP-style curriculum, the university’s relationship with Hanban, the Confucius Institute headquarters in Beijing, ended acrimoniously, and the LCI was closed.

Any other global university currently partnering with Confucius Institutes may in the future share Lyon’s fate.

All this points to a critical truth: The decision to host Confucius Institutes on campuses should not be devolved to universities but made by the state.

Unless they’re willing to see the CCP’s grip tighten on their own institutions, governments worldwide should move to ban Confucius Institutes from operating on university campuses.

All this points to a critical truth: The decision to host Confucius Institutes on campuses should not be devolved to universities but made by the state.

Unless they’re willing to see the CCP’s grip tighten on their own institutions, governments worldwide should move to ban Confucius Institutes from operating on university campuses.

Critics call this McCarthyism.

But such a state intervention would not be undermining but in fact restoring academic autonomy and freedom of speech.

Nobody is calling for intellectual restrictions or ideological tests for staff — merely for a recognition that money is power and that the CCP is ready to use it.

Such state intervention would also provide the necessary cover for universities to terminate their existing cooperation agreements with Confucius Institutes without being accused of picking a fight with the CCP.

Opponents of such a state intervention should bear in mind that Confucius Institutes—just like any other cultural organization operating overseas—could still register as civic groups and rent out office space off campus and continue their public relations work.

Opponents of such a state intervention should bear in mind that Confucius Institutes—just like any other cultural organization operating overseas—could still register as civic groups and rent out office space off campus and continue their public relations work.

This is how Western cultural organizations like the Goethe-Institut, British Council, and Institut Français operate globally.

Removing Confucius Institutes from universities could be considered an overdue standardization that brings them in line with common global practice.

Following such a ban, Confucius Institutes could also merge with China Cultural Centers, another Chinese cultural organization that operates with more than 30 branches worldwide.

But governments and universities alike should make up for the limited loss of revenue by fully funding Chinese language and contemporary Chinese studies provision.

Following such a ban, Confucius Institutes could also merge with China Cultural Centers, another Chinese cultural organization that operates with more than 30 branches worldwide.

But governments and universities alike should make up for the limited loss of revenue by fully funding Chinese language and contemporary Chinese studies provision.

If China matters, they should put their money where their mouth is.

It remains the responsibility of Western educators to proactively engage Chinese students and scholars as individuals and take the lead in introducing domestic students to mainland China, rather than letting the CCP and its outlets own the China story.

Shuping Yang

Shuping Yang Sophie Richardson testifying.

Sophie Richardson testifying.