By Justin Rohrlich

The restricted components are specifically barred from export to China, under US law.

US federal agents arrested a Chinese attempting to obtain hundreds of radiation-hardened microchips typically used in satellites and ballistic missile systems as he tried to leave the United States last year, according to court documents obtained by Quartz.

The bust, which had not been reported in the media until now, was the culmination of an elaborate international sting that stretched from China to Arizona, and included an undercover operation in Bangkok.

The made-to-order chip is manufactured and sold in the United States by Cobham, a multinational defense contractor headquartered in Britain.

The made-to-order chip is manufactured and sold in the United States by Cobham, a multinational defense contractor headquartered in Britain.

They cost $2,500 each, and the company only makes about 1,000 of them a year.

They are made to withstand extreme temperatures, severe vibrations, and radiation exposure.

Known as “rad-hard chips,” they require a license from the Department of Commerce to export, and sending the chips to China—as well as a small handful of other countries, including Russia—is banned outright.

A commercial version of the same chip, with the same memory capacity but without the ability to survive in the harsh conditions of outer space, goes for about $60.

A 2011 attempt by the Chinese to obtain an earlier version of the same chip was also foiled by the Department of Homeland Security.

A 2011 attempt by the Chinese to obtain an earlier version of the same chip was also foiled by the Department of Homeland Security.

But more than 100 of the 312 chips purchased by the suspect in that case remain missing.

In this latest case, authorities say Jian Fun Tso, who goes by Steven, emailed Cobham in January 2018 to ask about purchasing the microchips for a group of unidentified customers.

In this latest case, authorities say Jian Fun Tso, who goes by Steven, emailed Cobham in January 2018 to ask about purchasing the microchips for a group of unidentified customers.

He said the buyers intended to use the chips in a radar-assisted parking device for cars.

Tso called the sales potential “huge.”

According to prosecutors, Tso’s clients were based in China.

A Cobham representative told Tso that, although his managers would certainly love “huge” numbers, the chips he was inquiring about—aside from being illegal to ship to China—cost far more than anyone creating such a product would ever need to spend.

Nicholas Eftimiades, a veteran intelligence officer who held positions with the CIA, the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, and the Defense Intelligence Agency during his 34-year career, said the technology in radiation-hardened microchips is “very, very closely guarded.”

A Cobham representative told Tso that, although his managers would certainly love “huge” numbers, the chips he was inquiring about—aside from being illegal to ship to China—cost far more than anyone creating such a product would ever need to spend.

Nicholas Eftimiades, a veteran intelligence officer who held positions with the CIA, the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, and the Defense Intelligence Agency during his 34-year career, said the technology in radiation-hardened microchips is “very, very closely guarded.”

He said Tso’s explanation of how his clients would use them was nothing short of “ridiculous.”

“That chip could only be used by a certain number of state institutions in China, all leading to the People’s Liberation Army,” Eftimiades told Quartz.

“That chip could only be used by a certain number of state institutions in China, all leading to the People’s Liberation Army,” Eftimiades told Quartz.

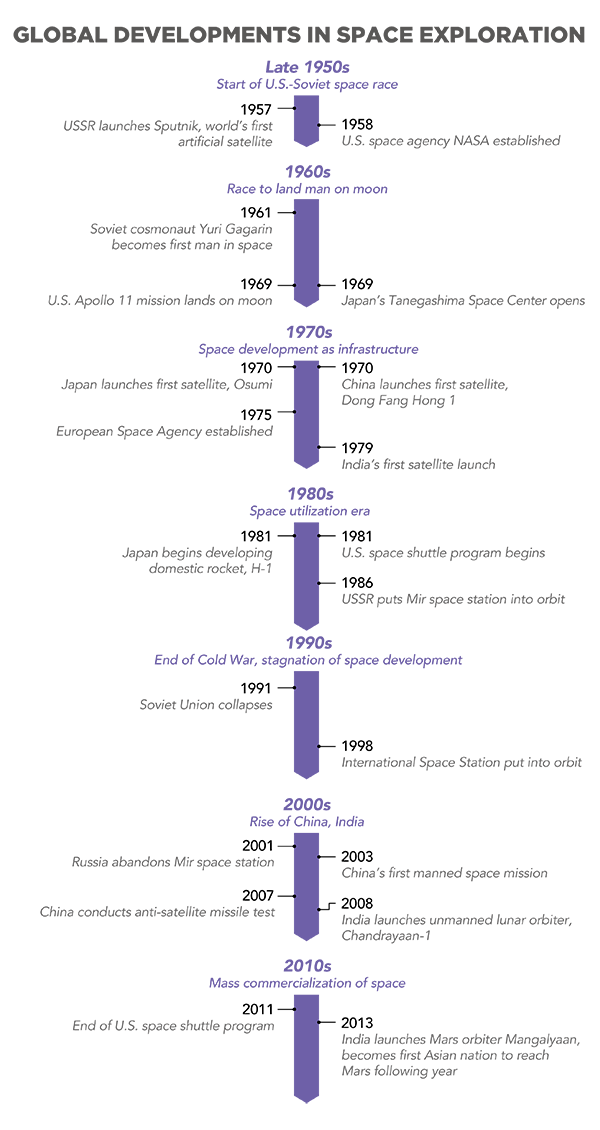

“They’re trying to steal it in a covert manner, the likelihood is a military space program or missile program.”

Court documents quote a Cobham official saying there was “absolutely no rational reason” for anyone to use the chip in an automotive application.

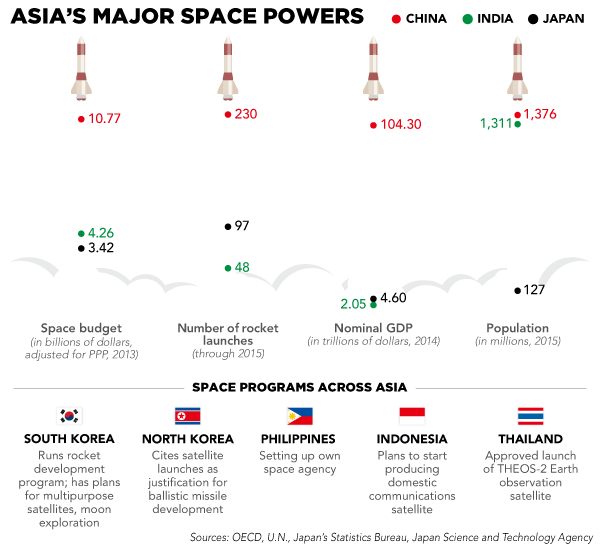

China, which maintains the most extensive intelligence apparatus in the world, has increased the size and scope of its efforts in recent years.

China, which maintains the most extensive intelligence apparatus in the world, has increased the size and scope of its efforts in recent years.

Beijing’s attempts to acquire sensitive American technology target not just the US government and the defense industry, but major universities and research scientists as well.

Chinese hackers have already compromised dozens of critical US weapons systems.

Chinese hackers have already compromised dozens of critical US weapons systems.

In 2018, Chinese hackers stole top-secret plans for a supersonic anti-ship missile the Navy was developing.

Last fall, two Chinese diplomats living in the United States—one of whom authorities believe was in fact an undercover intelligence officer—were expelled from the country after attempting to get onto a secure Virginia military base.

Authorities recently charged a Chinese tour guide in San Francisco with passing US secrets to China’s Ministry of State Security.

And last month, two different Chinese were caught surveilling the same Florida military base twice in two weeks.

“The Chinese have been eating our lunch since the eighties,” former CIA officer Robert Baer told Quartz.

“The Chinese have been eating our lunch since the eighties,” former CIA officer Robert Baer told Quartz.

“Every single scientific and technological breakthrough they’ve made is thanks to what they’ve ripped off from us. And it’s only getting worse. Chinese theft of our technology is up there with our worst national security threats.”

Tso tries again

According to court filings, Cobham—which in 2018 alone received eight requests from Chinese entities for the valuable microchips—reported Tso’s call to US counterintelligence.

Unable to get the chips from Cobham, Tso tried a US electronics distributor that acts as a reseller. This time, Tso left out the part about China being the chips’ ultimate destination.

The distributor emailed Tso a blank end user agreement to fill out.

To Bangkok and back

In November 2018, some 10 months after Tso’s original email to Cobham, the undercover agent met him at the Bangkok Intercontinental Hotel to finalize the deal.

Tso, who brought his wife to the rendezvous, asked the agent to provide him with a set of false invoices reflecting a total price of $10,000 for the $550,000 worth of chips, saying it would help him avoid any potential problems with customs if he were stopped.

That’s when Tso admitted the chips were ultimately destined for China.

Tso tries again

According to court filings, Cobham—which in 2018 alone received eight requests from Chinese entities for the valuable microchips—reported Tso’s call to US counterintelligence.

Unable to get the chips from Cobham, Tso tried a US electronics distributor that acts as a reseller. This time, Tso left out the part about China being the chips’ ultimate destination.

The distributor emailed Tso a blank end user agreement to fill out.

Tso returned it, listing the end user as an electrical engineer named “John Anderson” from Metech ICT, an automotive electronics company based in Liverpool, England.

Like Cobham, the distributor found his request suspicious and referred him to an undercover agent with the Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS).

Tso soon made contact with the undercover agent, who was stationed in Phoenix, Arizona.

Tso soon made contact with the undercover agent, who was stationed in Phoenix, Arizona.

He sent the agent, who claimed to work for the distribution company, a purchase order for the chips. DCIS checked the information Tso provided for Metech ICT against the UK corporate registration database.

No one named John Anderson worked there.

The address Tso provided was for a restaurant he ran in Liverpool.The undercover agent agreed to sell 200 chips to Tso, who said he planned to pick them up in the United States and personally take them back to the UK.

Tso said he would wire the undercover agent 50% of the payment up front, and the remainder upon delivery, transferring his own money from Hong Kong to the UK and then on to the United States, claiming the nonexistent John Anderson would reimburse him later.

In what Eftimiades describes as a “whole of society approach,” the Chinese security services deploy overseas agents who range from trained intelligence officers to rank amateurs who engage in comically bad spycraft.

In what Eftimiades describes as a “whole of society approach,” the Chinese security services deploy overseas agents who range from trained intelligence officers to rank amateurs who engage in comically bad spycraft.

Non-professional “freelance” operatives like Tso tend to do it for the money, and often become involved through personal networks.

It’s all part of a worldwide program to steal information that will increase Chinese power economically and politically, former CIA officer Joseph Wippl told Quartz.

It’s all part of a worldwide program to steal information that will increase Chinese power economically and politically, former CIA officer Joseph Wippl told Quartz.

“It is not limited to the United States, although we are the priority No. 1 target,” he said.

To Bangkok and back

In November 2018, some 10 months after Tso’s original email to Cobham, the undercover agent met him at the Bangkok Intercontinental Hotel to finalize the deal.

Tso, who brought his wife to the rendezvous, asked the agent to provide him with a set of false invoices reflecting a total price of $10,000 for the $550,000 worth of chips, saying it would help him avoid any potential problems with customs if he were stopped.

That’s when Tso admitted the chips were ultimately destined for China.

Tso also confided to the undercover agent that the money he sent from the UK had in fact originated in Hong Kong and China, and that Metech ICT was a front company he had set up.

As long as they were “both protected,” the agent told Tso this was fine.

As long as they were “both protected,” the agent told Tso this was fine.

Tso called a female contact he referred to as “Big Sister,” who told the undercover agent she planned to meet Tso in the UK and hand-carry the chips from there to Hong Kong.

“Other individuals” would transport the chips from Hong Kong to China, Big Sister said.

The following month, Tso wired a payment of $275,000 to the undercover agent’s bank account, which was $10,000 more than the actual balance due.

The following month, Tso wired a payment of $275,000 to the undercover agent’s bank account, which was $10,000 more than the actual balance due.

Tso, who had given his customers a purposely inflated price, was planning to keep the extra money for himself and asked to be reimbursed when he arrived in Phoenix to pick up the chips.

On January 14, 2019, Tso flew from Liverpool to Philadelphia, where he boarded a connection to Phoenix.

On January 14, 2019, Tso flew from Liverpool to Philadelphia, where he boarded a connection to Phoenix.

A day later, he met with the undercover agent, who gave Tso $10,000 in cash and a box he said contained the 200 radiation-hardened chips they had discussed.

The agent reminded Tso that it would be illegal to bring the chips from the UK to China, to which Tso responded that he “hoped” the chips would stay in the UK but that “the less he knew about the ultimate end user, the better.”

The next day the undercover agent drove Tso to Phoenix’ Sky Harbor airport.

The next day the undercover agent drove Tso to Phoenix’ Sky Harbor airport.

He was intercepted by US Customs and Border Protection as he attempted to board his flight.

Tso pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges a year later, just before his trial was set to begin.

Tso pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges a year later, just before his trial was set to begin.

He is scheduled to be sentenced April 13, and faces up to 20 years in prison and a $1 million fine.

Tso’s lawyer, Seth Apfel, declined to comment, as did the federal prosecutors handling the proceedings.

John Sipher, who spent 28 years in the CIA’s National Clandestine Service before retiring in 2014, told Quartz that the Tso case “mirrors dozens of other cases and is likely the tip of the iceberg.”

This time, Tso’s unlikely story for how the chips would be used gave away his intentions before it was too late, said Eftimiades.

Tso’s lawyer, Seth Apfel, declined to comment, as did the federal prosecutors handling the proceedings.

John Sipher, who spent 28 years in the CIA’s National Clandestine Service before retiring in 2014, told Quartz that the Tso case “mirrors dozens of other cases and is likely the tip of the iceberg.”

This time, Tso’s unlikely story for how the chips would be used gave away his intentions before it was too late, said Eftimiades.

“When someone’s putting $200,000 out, not asking for financing, and they don’t know the [real] use of the chip, it becomes apparent very quickly that this is a lie.”