Journalists are denied visas and editors receive threatening emails

By Richard Orange in Malmö

Swedish media was moved to make the statement after a cartoon in the Danish magazine Jyllands-Posten came under similar pressure from Chinese officials.

Sweden’s leading newspapers and broadcasters have together called on their government to take stronger action against China for its “unacceptable” repeated attacks on the country’s media, which have included visa bans and threats.

In a strongly worded statement, Utgivarna, which represents Sweden’s private and public sector media, complained that journalists had been put under intense pressure by Chinese government representatives.

“Time and again, China’s ambassador Gui Congyou has tried to undermine the freedom of the press and the freedom of expression under the Swedish constitution with false statements and threats,” the statement read.

It said journalists had been denied visas, while editors received a near-constant stream of threatening and critical emails and phone calls.

“It is unacceptable that the world’s largest dictatorship is trying to prevent free and independent journalism in a democracy like Sweden. These repeated attacks must cease immediately,” the statement said.

It said the government should raise the issue at EU level and together with other member states “strongly protest” over the attacks on press freedom.

Tensions between Sweden and China have been rising since 2015, when Chinese agents seized the dissident Chinese publisher Gui Minhai while he was on holiday in Thailand.

In a strongly worded statement, Utgivarna, which represents Sweden’s private and public sector media, complained that journalists had been put under intense pressure by Chinese government representatives.

“Time and again, China’s ambassador Gui Congyou has tried to undermine the freedom of the press and the freedom of expression under the Swedish constitution with false statements and threats,” the statement read.

It said journalists had been denied visas, while editors received a near-constant stream of threatening and critical emails and phone calls.

“It is unacceptable that the world’s largest dictatorship is trying to prevent free and independent journalism in a democracy like Sweden. These repeated attacks must cease immediately,” the statement said.

It said the government should raise the issue at EU level and together with other member states “strongly protest” over the attacks on press freedom.

Tensions between Sweden and China have been rising since 2015, when Chinese agents seized the dissident Chinese publisher Gui Minhai while he was on holiday in Thailand.

Gui Minhai, a Swedish citizen, is still being held by Chinese authorities and his case has been heavily covered by the Swedish media.

The friction has increased since Gui Congyou (no relation) was appointed China’s ambassador in November 2017.

In November last year he threatened that China would “surely take counter-measures” after Sweden’s culture minister, Amanda Lind, attended a ceremony to award Gui Minhai the Tucholsky prize for writers facing persecution.

This month he was summoned to see Sweden’s foreign minister, Ann Linde, after he described the relationship between the Swedish media and the Chinese state using an analogy that many interpreted as threatening.

“It is like when a lightweight boxer is trying to provoke a fight with a heavyweight boxer, and said heavyweight boxer is kindly encouraging the lightweight to mind his own business, out of goodwill,” he told Sweden’s state broadcaster SVT.

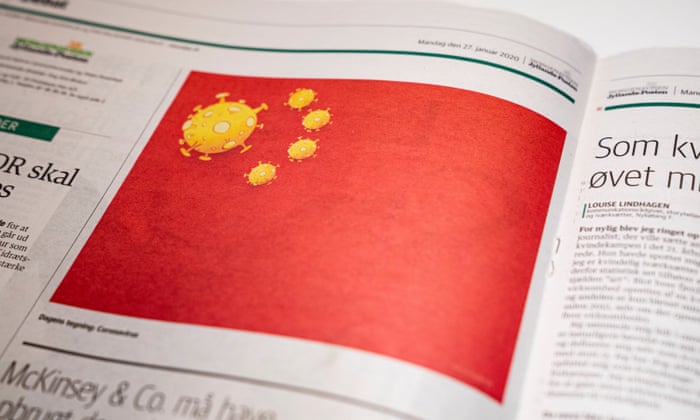

On Tuesday the Chinese embassy to Denmark demanded an apology for a cartoon published in Jyllands-Posten.

The latest cartoon, which altered the Chinese flag to stars with viruses, was “an insult to China” and “hurts the feelings of the sick Chinese people”, the embassy said.

Patrik Hadenius, the chief executive of Utgivarna, said his members had felt moved to act after they saw Danish media coming under similar pressure.

“It’s not just a problem for Sweden but a problem for all democratic countries. Just the other day it happened in Denmark,” he said.

The friction has increased since Gui Congyou (no relation) was appointed China’s ambassador in November 2017.

In November last year he threatened that China would “surely take counter-measures” after Sweden’s culture minister, Amanda Lind, attended a ceremony to award Gui Minhai the Tucholsky prize for writers facing persecution.

This month he was summoned to see Sweden’s foreign minister, Ann Linde, after he described the relationship between the Swedish media and the Chinese state using an analogy that many interpreted as threatening.

“It is like when a lightweight boxer is trying to provoke a fight with a heavyweight boxer, and said heavyweight boxer is kindly encouraging the lightweight to mind his own business, out of goodwill,” he told Sweden’s state broadcaster SVT.

On Tuesday the Chinese embassy to Denmark demanded an apology for a cartoon published in Jyllands-Posten.

The latest cartoon, which altered the Chinese flag to stars with viruses, was “an insult to China” and “hurts the feelings of the sick Chinese people”, the embassy said.

Patrik Hadenius, the chief executive of Utgivarna, said his members had felt moved to act after they saw Danish media coming under similar pressure.

“It’s not just a problem for Sweden but a problem for all democratic countries. Just the other day it happened in Denmark,” he said.

“We felt we needed to lift this to higher levels.”