By Simon Denyer

An officer with Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force looks out over a new base on the Japanese island of Miyako on July 28.

MIYAKO, Japan — A high-stakes “game of chicken” is playing out in the East China Sea, as Beijing pokes and provokes Tokyo with an intensifying campaign of aerial and maritime encroachments designed to challenge Japan’s control of its islands.

Every day, around the clock, Japan scrambles fighter jets and dispatches coast guard vessels to counter some new Chinese provocation and ward off the intruding boats and planes.

Every day, around the clock, Japan scrambles fighter jets and dispatches coast guard vessels to counter some new Chinese provocation and ward off the intruding boats and planes.

It is also building a “wall” of defensive installations, including missile bases, along the chain of subtropical, touristed islands that make up the archipelago’s southwestern arc.

“China wants to change the status quo, but it does not want a military confrontation,” said Michael Bosack, a special adviser at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies in Japan.

“China wants to change the status quo, but it does not want a military confrontation,” said Michael Bosack, a special adviser at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies in Japan.

“The problem here is that miscalculation may lead to confrontation and/or escalation.”

The contest has prompted a shift in Japan’s defense strategy.

The contest has prompted a shift in Japan’s defense strategy.

Over the past few years, the country has significantly expanded its air force and coast guard bases centered on the southwestern island of Okinawa, which already hosts tens of thousands of U.S. troops and the largest U.S. air base in the Asia-Pacific.

A 2,100-strong Japanese Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade, the first of its kind, was created in March 2018, with a mandate to defend — and if necessary, retake — Japanese islands that could be targets of invasions.

Military bases are being established on more-remote islands stretching west toward Taiwan, to house troops and missiles capable of defending territory, waterways and airspace.

A 2,100-strong Japanese Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade, the first of its kind, was created in March 2018, with a mandate to defend — and if necessary, retake — Japanese islands that could be targets of invasions.

Military bases are being established on more-remote islands stretching west toward Taiwan, to house troops and missiles capable of defending territory, waterways and airspace.

Defense experts call it the “southwestern wall.”

On the island of Miyako, among sugar-cane fields, Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force opened a new base in March that will accommodate 700 to 800 troops, anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries, and radar and intelligence-gathering facilities.

A similar base was established on the island of Amami Oshima at the same time.

On the island of Miyako, among sugar-cane fields, Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force opened a new base in March that will accommodate 700 to 800 troops, anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries, and radar and intelligence-gathering facilities.

A similar base was established on the island of Amami Oshima at the same time.

A smaller facility opened on the westernmost island of Yonaguni in 2016, and another is planned for the island of Ishigaki by 2021, each forming a brick in the wall.

The territorial dispute centers on five small, uninhabited islands controlled by Japan and known as the Senkakus.

Tensions over those islands have flared in recent years as Beijing has sought to assert its maritime claims more aggressively, especially since Japan purchased three of the islands from a private owner in 2012 and China declared an air defense identification zone covering the area in 2013.

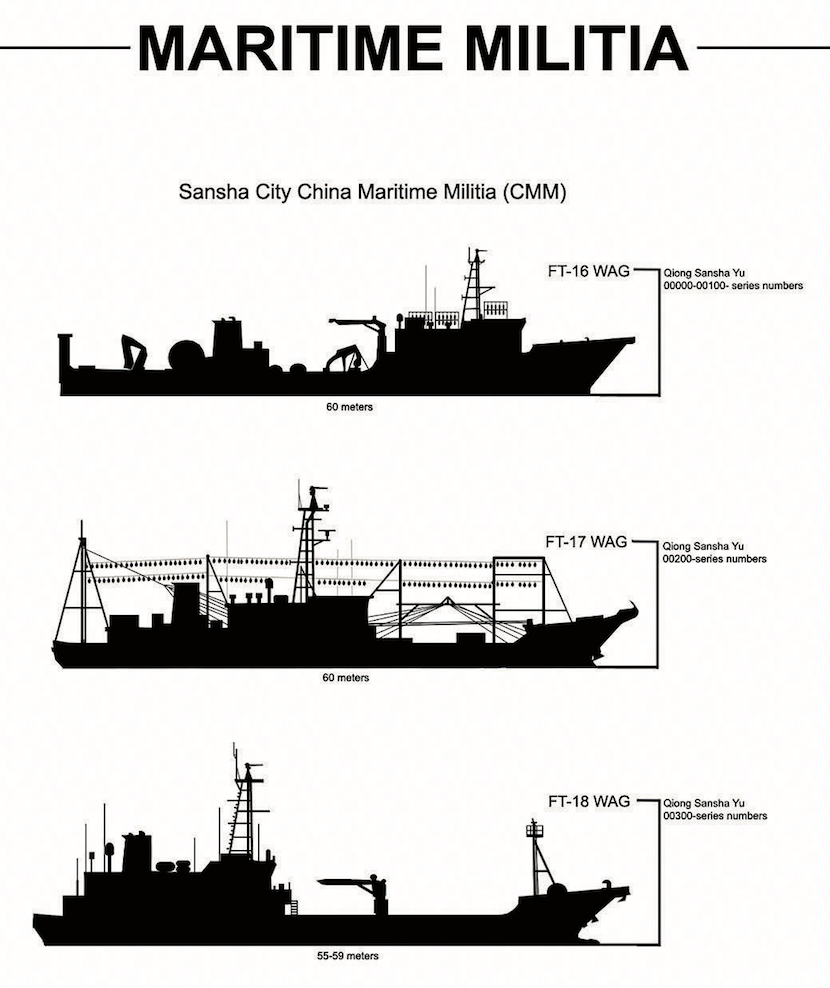

Since then, armed Chinese coast guard vessels and armed fishing boats known as the “maritime militia” have been regular visitors to the territorial seas around the Senkakus and to the wider contiguous zone between 12 and 24 nautical miles from the islands.

The territorial dispute centers on five small, uninhabited islands controlled by Japan and known as the Senkakus.

Tensions over those islands have flared in recent years as Beijing has sought to assert its maritime claims more aggressively, especially since Japan purchased three of the islands from a private owner in 2012 and China declared an air defense identification zone covering the area in 2013.

Since then, armed Chinese coast guard vessels and armed fishing boats known as the “maritime militia” have been regular visitors to the territorial seas around the Senkakus and to the wider contiguous zone between 12 and 24 nautical miles from the islands.

Between April and June, Chinese ships penetrated that area for a record 64 consecutive days, Japan says.

Not everyone on Miyako island is a fan of Japan's new military base

Not everyone on Miyako island is a fan of Japan's new military base

Experts refer to these tactics as “gray zone” operations, intended to gain an advantage without provoking military conflict.

“China engages in unilateral, coercive attempts to alter the status quo based on its own assertions that are incompatible with the international order,” Japan’s Defense Ministry said in its latest strategy paper, adding that “expanding and intensifying military activities at sea and in the air” represent a serious security concern.

China denies its moves are expansionist or aggressive but says it has an “unshakable will” to uphold its "territorial sovereignty".

It is the same language that China uses to defend similar tactics in the South China Sea, where it has built a string of artificial islands equipped with military facilities in disputed waters.

In the East China Sea, Japan and China are competing not only for control of the disputed Senkaku islands but for dominion over the broader western Pacific Rim.

The Japanese archipelago forms part of the “first island chain,” a string of island groups stretching across East Asia from Russia to Borneo.

“China engages in unilateral, coercive attempts to alter the status quo based on its own assertions that are incompatible with the international order,” Japan’s Defense Ministry said in its latest strategy paper, adding that “expanding and intensifying military activities at sea and in the air” represent a serious security concern.

China denies its moves are expansionist or aggressive but says it has an “unshakable will” to uphold its "territorial sovereignty".

It is the same language that China uses to defend similar tactics in the South China Sea, where it has built a string of artificial islands equipped with military facilities in disputed waters.

In the East China Sea, Japan and China are competing not only for control of the disputed Senkaku islands but for dominion over the broader western Pacific Rim.

The Japanese archipelago forms part of the “first island chain,” a string of island groups stretching across East Asia from Russia to Borneo.

During the Cold War, the United States saw control of this island chain as a way to contain the Soviet Union and China; these days, Beijing wants to break the chain to gain untrammeled access to the Pacific.

Japan’s new island bases are also intended to monitor and protect two key waterways in that chain, the Miyako and Tokara straits.

China contests Japan’s right to control those waters, and last month its aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, sailed through the Miyako Strait for the third time in just over a year.

Its fighters and bombers take similar routes.

China has the right of passage under international maritime law, but Japan bristles to see so much military hardware crossing freely between the links in its island chain.

China has the right of passage under international maritime law, but Japan bristles to see so much military hardware crossing freely between the links in its island chain.

It scrambled its warplanes a record 851 times in 2016 and 179 times between April and June this year.

The Center for International and Strategic Studies calls the situation a “slow-moving crisis”, warning that an accidental collision could easily spiral into conflict.

The Center for International and Strategic Studies calls the situation a “slow-moving crisis”, warning that an accidental collision could easily spiral into conflict.

The Rand Corp. warns that China’s steady escalation and increasingly provocative penetrations could “strain Japan’s capacity to respond” while avoiding the risk of an armed conflict that could potentially draw in the United States.

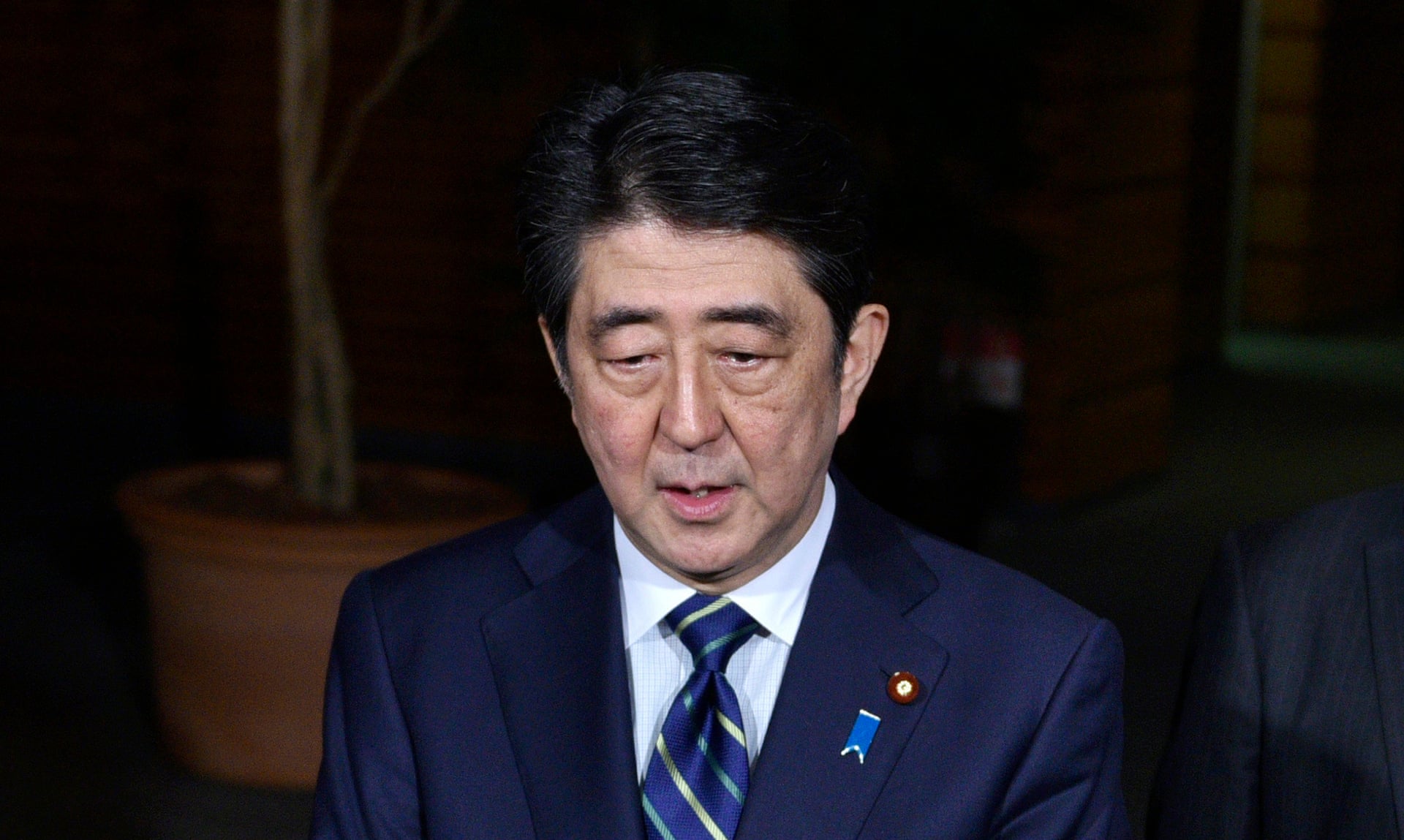

The standoff is already straining domestic politics in Japan, where defense spending has fallen far behind China’s in the past three decades and efforts by the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to reverse the downtrend have proved controversial.

On the islands, resistance to the new Japanese bases is significant.

The standoff is already straining domestic politics in Japan, where defense spending has fallen far behind China’s in the past three decades and efforts by the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to reverse the downtrend have proved controversial.

On the islands, resistance to the new Japanese bases is significant.

On Miyako, a small but determined group of protesters says the Defense Ministry lied about its plans to store missiles there and does not prioritize the islanders’ welfare and safety.

Like the people of Okinawa’s main island who are protesting against U.S. bases, people of this once independent region remember bitterly how civilians suffered here in intense fighting between American and Japanese troops during World War II.

Like the people of Okinawa’s main island who are protesting against U.S. bases, people of this once independent region remember bitterly how civilians suffered here in intense fighting between American and Japanese troops during World War II.

Many want no part in big nations’ wars.

Similar protests and petitions signed by thousands have slowed construction of the Ishigaki base and stalled the deployment of a U.S.-made missile defense system in Akita in northern Japan and Yamaguchi in western Japan and Osprey aircraft in Saga in the southwest.

Japan’s government has acknowledged it needs to better manage local concerns but insists it will not be deterred from its strategic goals.

As well as bolstering its own defenses, Japan’s navy says it has also increased the frequency of joint exercises with friends and allies such as the United States, Australia and India as it seeks to build what it calls a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

Similar protests and petitions signed by thousands have slowed construction of the Ishigaki base and stalled the deployment of a U.S.-made missile defense system in Akita in northern Japan and Yamaguchi in western Japan and Osprey aircraft in Saga in the southwest.

Japan’s government has acknowledged it needs to better manage local concerns but insists it will not be deterred from its strategic goals.

As well as bolstering its own defenses, Japan’s navy says it has also increased the frequency of joint exercises with friends and allies such as the United States, Australia and India as it seeks to build what it calls a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

_MoD.jpg/1200px-HMS_Sutherland_(F81)_MoD.jpg)