China land grab on Lake Baikal raises Russian ire

By Charles Clover and Archie Zhang in Beijing

The town of Listvyanka on Lake Baikal in winter. The town is popular with Chinese tourists and property investors

A sleepy tourist town on the shores of Siberia’s Lake Baikal has become an unlikely lightning rod among Russian nationalists after Chinese investors bought up properties on the town’s lakefront.

Russian newspapers have inflamed public opinion over the town of Listvyanka, running headlines about a Chinese “invasion”, “conquest” and even China’s “yoke” — a reference to the Mongol invasions of the Middle Ages.

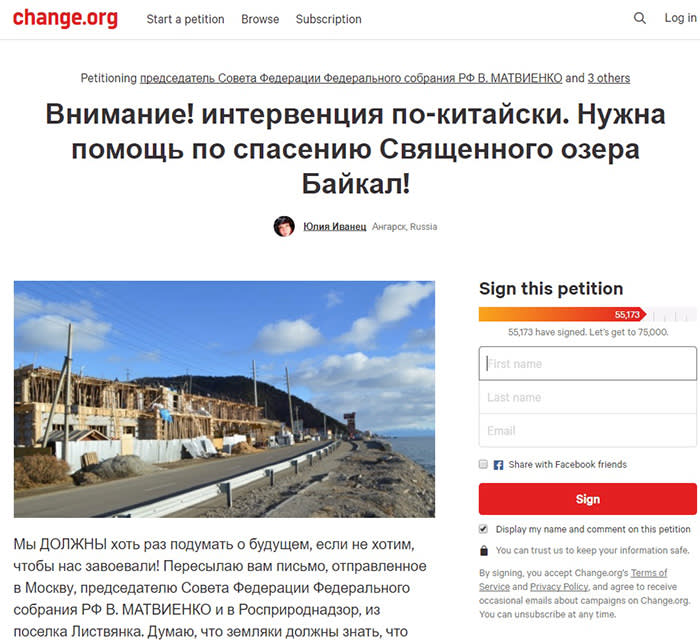

An online petition with 55,000 signatures (Listvyanka has a population of less than 2,000) claims that Beijing is seeking to transform the area into a Chinese province, and asks Russia’s President Vladimir Putin to ban land sales to the Chinese there.

The petition has received wide coverage in newspapers including Moskovsky Komsomolets, a national tabloid.

“The people are in a panic! The authorities are inactive, but if this situation will not change, we will continue to lose our underbelly! Our property!” reads the petition on the website Change.org published by Yulia Ivanets, who is identified by her page on Russian social media site Vkontakte as being from the neighbouring town of Angarsk.

“We have let the goat into the garden,” she wrote.

Ms Ivanets did not respond to emails and messages on social media.

The message fuels familiar Russian fears about its more prosperous and populous neighbour — the sparsely populated and economically undeveloped eastern third of Russia is vulnerable to large scale Chinese immigration.

But these local tensions are at odds with the diplomatic efforts of both countries’ leaders, and threaten to frustrate grand designs of a budding Russian-Chinese pseudo-alliance.

The two countries have a “comprehensive strategic partnership of co-ordination [that] has continuously been running at a high level over the past year”, said Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, during a visit to Moscow last month.

Russia needs investment by China to help its economy, which has been hit by western sanctions in the aftermath of its invasion of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, China has made a priority of investing in Russia and other Eurasian countries as part of its Belt and Road strategy of building infrastructure across the region.

But at a local level, mutual mistrust and cultural insensitivity threaten to undo the careful diplomatic work of both countries’ leaders.

Viktor Sin’kov, head of the legal department in Listvyanka’s municipal government, said Chinese property development in the town had angered residents.

“People really are worried about the Chinese buying everything here. They build huge hotels. They tear down and change the façades,” he said.

“Their advertisements are everywhere, hanging from fences.”

An online petition against perceived efforts to turn the area into a Chinese province

While Ms Ivanets’ petition claimed that 10 per cent of the town’s prime real estate had been bought by Chinese developers, Mr Sin’kov said: “Ten per cent is an exaggeration. It’s a lot less than that.”

But he said that Chinese tour groups made a point of telling visitors that Lake Baikal — the world’s deepest freshwater lake — was part of China during the Tang and Han dynasties.

“This means they want it back,” said Mr Sin’kov.

Indeed, Chinese tourism websites claim that Lake Baikal was once part of China.

Cassia, a Chinese travel agency, advertised trips to Lake Baikal recalling its Chinese past: “It was called the Northern Sea during the Han Dynasty . . . it had been China’s territory for a long time in history.”

Chinese tourists report a largely friendly reception by their Russian hosts, especially in winter — traditionally the low season in Siberian tourism.

Shen Zhefan, a video producer from Shanghai, travelled to Lake Baikal last month, anxious to see the famous frozen lake and wide expanses of snow.

“When I was there, almost all the tourists were Chinese,” he said.

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est China’s land grab. Afficher tous les articles

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est China’s land grab. Afficher tous les articles

jeudi 4 janvier 2018

samedi 26 août 2017

Chinese Aggressions

China’s latest moves in the South China Sea have sparked fears of a new land grab

By Steve Mollman

Filipino patriotism on Thitu Island.

By Steve Mollman

Filipino patriotism on Thitu Island.

In 2012, China wrested control of Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea from the Philippines. With the shoal—reefs, rocks, and a vast lagoon—located just 220 km (137 miles) from the Philippines’ main island Luzon, the incident heightened tensions and embarrassed Manila, which the following year opened a case in an international tribunal challenging Beijing’s territorial moves in the sea.

So alarm bells went off earlier this month when Chinese ships gathered at Sandy Cay, a set of sandbars close to Philippines-occupied Thitu Island in the sea’s Spratly archipelago.

The governments of both countries have remained tight-lipped about the murky incident.

When the tribunal made its ruling, it went by the rules of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), which is at the core of modern maritime law.

Testing the waters

For China, occupying the sandbar would probably not matter much right now.

It’s possible that China, by occupying Sandy Cay—or simply putting a flotilla near it—could be testing the waters in terms of reactions in the Philippines.

“I think the occupation of Sandy Cay would be a useful way for China to test the Philippines (and to a lesser extent the US),” Ku added.

The Spratly archipelago.

So alarm bells went off earlier this month when Chinese ships gathered at Sandy Cay, a set of sandbars close to Philippines-occupied Thitu Island in the sea’s Spratly archipelago.

The island has a small civilian population and a decrepit runway the Philippines has been meaning to repair.

The flotilla was seen as intimidating at the very least.

The flotilla was seen as intimidating at the very least.

“China’s ongoing maritime activity around Thitu is worrisome… if the objective of the operation is to occupy Sandy Cay, that would mean a significant escalation in tension in the South China Sea. Asia has acquired yet another flashpoint it could well do without,” wrote Euan Graham, a security analyst with the Lowy Institute for International Policy in Sydney.

A number of nations have claims to various features in the Spratlys.

A number of nations have claims to various features in the Spratlys.

China, for its part, claims nearly the entire sea for itself, based on its infamous nine-dash line.

The tribunal invalidated that sweeping claimin a nearly 500-page ruling issued in July 2016, but Beijing dismissed the legal proceedings entirely.

Satellite images shared by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, based in Washington, DC, confirmed the presence of the flotilla, which included fishing, coastguard, and navy ships.

Satellite images shared by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, based in Washington, DC, confirmed the presence of the flotilla, which included fishing, coastguard, and navy ships.

The Philippines military confirmed it as well.

It’s unclear at the time of this writing whether the vessels are still present.

Filipinos living on Thitu Island.

Filipinos living on Thitu Island.

The governments of both countries have remained tight-lipped about the murky incident.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying said that people with ulterior motives were trying to “stir up conflicts between China and the Philippines.”

Philippines foreign minister Alan Peter Cayetano said the mere presence of the Chinese ships was no cause for alarm “despite the lack of details that we give you,” saying the matter would be resolved through diplomatic channels.

That followed similar reassurances a day earlier from Rodrigo Duterte.

But not everyone in the Philippines is so sure.

But not everyone in the Philippines is so sure.

The Chinese ships were reportedly blocking access to Sandy Cay, about 5 km (3.1 miles) from Thitu Island.

They also blocked a vessel from the Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, according to lawmaker Gary Alejano, who last week shared photos of the Chinese ships.

For many Filipinos the thought of a Chinese blockade dredges up bad memories.

When China took over Scarborough Shoal, it blocked Philippine ships from accessing it.

A contested sea.

Something for Subi

If China did occupy Sandy Cay (not to be confused with the nearby Sand Cay) and claim territorial waters around it, that could bolster the legal status of another nearby feature: Subi Reef, where China has built a militarized artificial island.

Something for Subi

If China did occupy Sandy Cay (not to be confused with the nearby Sand Cay) and claim territorial waters around it, that could bolster the legal status of another nearby feature: Subi Reef, where China has built a militarized artificial island.

A sandbar seen from Thitu Island.

When the tribunal made its ruling, it went by the rules of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), which is at the core of modern maritime law.

The tribunal designated Subi Reef a “low-tide elevation.”

Such legal designations matter a great deal, as they determine what kind of rights a nation gets in the surrounding waters.

Under Unclos, a “low-tide elevation”—above water at low tide but submerged at high tide—generates no territorial sea.

Under Unclos, a “low-tide elevation”—above water at low tide but submerged at high tide—generates no territorial sea.

A territorial sea extends out 12 nautical miles (22 km or 13.9 miles) from shore, and within it a nation can better enforce its rules.

A “rock,” by contrast, does generate a territorial sea.

A “rock,” by contrast, does generate a territorial sea.

An “island” generates an exclusive economic zone, which grants a nation sole rights to natural resources in an area extending 200 nautical miles from the shore.

In its ruling, the tribunal didn’t determine Sandy Cay’s legal designation.

In its ruling, the tribunal didn’t determine Sandy Cay’s legal designation.

But Antonio Carpio, a Supreme Court senior associate justice in the Philippines, said on Aug. 19:

“Sandy Cay is a Philippine land territory that is being seized (to put it mildly), or being invaded (to put it frankly), by China. If China acquires sovereignty over Sandy Cay, it can now claim Subi Reef as part of the territorial sea of Sandy Cay, legitimizing China’s claim over Subi Reef.”

Carpio said Duterte should send navy vessels to defend Sandy Cay.

“Sandy Cay is a Philippine land territory that is being seized (to put it mildly), or being invaded (to put it frankly), by China. If China acquires sovereignty over Sandy Cay, it can now claim Subi Reef as part of the territorial sea of Sandy Cay, legitimizing China’s claim over Subi Reef.”

Carpio said Duterte should send navy vessels to defend Sandy Cay.

Were China to start a skirmish with them, he noted, the government could then invoke the mutual defense treaty with the US.

Duterte, however, said he would not invoke the treaty in such a case: “I will not call on America. I have lost trust in the Americans.”

In a situation where Sandy Cay was designated a “rock” and China established sovereignty over it, its territorial sea would be extended by Subi Reef, noted Conor Cronin, a research associate with the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

In a situation where Sandy Cay was designated a “rock” and China established sovereignty over it, its territorial sea would be extended by Subi Reef, noted Conor Cronin, a research associate with the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

In other words, Subi Reef would then generate territorial waters.

That’s something Subi Reef doesn’t have now, and didn’t have when the US conducted a nearby “freedom of navigation” operation challenging China’s claims in 2015.

The USS Lassen’s 2015 freedom of navigation operation near Subi Reef.

The USS Lassen’s 2015 freedom of navigation operation near Subi Reef.

That’s something Subi Reef doesn’t have now, and didn’t have when the US conducted a nearby “freedom of navigation” operation challenging China’s claims in 2015.

The USS Lassen’s 2015 freedom of navigation operation near Subi Reef.

The USS Lassen’s 2015 freedom of navigation operation near Subi Reef.Testing the waters

For China, occupying the sandbar would probably not matter much right now.

But one day, it might.

“I suppose that in a future world where China and the Philippines agree to divide up sovereignty over the islands and rocks, China is better off with Sandy Cay if it ever had to give up its claim to Thitu Island,” said Julian Ku, a professor at the law school of Hofstra University in New York.

Thitu Island seen from the sky.

Thitu Island seen from the sky.

“I suppose that in a future world where China and the Philippines agree to divide up sovereignty over the islands and rocks, China is better off with Sandy Cay if it ever had to give up its claim to Thitu Island,” said Julian Ku, a professor at the law school of Hofstra University in New York.

Thitu Island seen from the sky.

Thitu Island seen from the sky.It’s possible that China, by occupying Sandy Cay—or simply putting a flotilla near it—could be testing the waters in terms of reactions in the Philippines.

“I think the occupation of Sandy Cay would be a useful way for China to test the Philippines (and to a lesser extent the US),” Ku added.

“As a legal matter, the Philippines also claims Sandy Cay, and if they allow China to occupy it… it would be a signal the Philippines will not resist Chinese changes to the status quo.”

Another theory is that China is trying to intimidate the Philippines against building at Sandy Cay itself, or against bolstering its presence on Thitu Island.

Either way, the flotilla has given Asia one more flashpoint to worry about.

Another theory is that China is trying to intimidate the Philippines against building at Sandy Cay itself, or against bolstering its presence on Thitu Island.

Either way, the flotilla has given Asia one more flashpoint to worry about.

jeudi 17 août 2017

Chinese Peril

China’s secret threat to Australia’s Antarctic claim

AAP

An aerial view of Antarctica, as seen from a Qantas Jumbo sightseeing flight.

AUSTRALIA must wise up to secret Chinese military activities and the threat of a land grab for resources in Antarctica, a report warns.

Research from defence think tank the Australian Strategic Policy Institute says Australia’s leadership role is being eroded because of long-term under-investment at a time when other countries are expanding their presence and influence in the region.

“China has conducted undeclared military activities in Antarctica, is building up a case for a territorial claim, and is engaging in minerals exploration there,” the report says.

“The calculation that the Australian government has long made in short-changing Antarctic affairs in order to boost activities up north is looking increasingly risky.”

“China has never stopped exploring Antarctic mineral resources, despite the requirements of the Madrid Protocol,” the report said.

Exploration activities have stepped up since 2012 including preliminary surveys of coal reserves and investigations of undersea metal deposits.

AAP

An aerial view of Antarctica, as seen from a Qantas Jumbo sightseeing flight.

AUSTRALIA must wise up to secret Chinese military activities and the threat of a land grab for resources in Antarctica, a report warns.

Research from defence think tank the Australian Strategic Policy Institute says Australia’s leadership role is being eroded because of long-term under-investment at a time when other countries are expanding their presence and influence in the region.

“China has conducted undeclared military activities in Antarctica, is building up a case for a territorial claim, and is engaging in minerals exploration there,” the report says.

“The calculation that the Australian government has long made in short-changing Antarctic affairs in order to boost activities up north is looking increasingly risky.”

China has ceased being a minor player in the polar regions and is becoming a major actor as a result of a huge budget increase in the past decade.

Beijing is operating two icebreakers down south and has a third under construction.

The report, by Anne-Marie Brady, noted three out of four of China’s Antarctic bases and two of its field camps are in the Australian Antarctic Territory.

Australia’s territorial claim in Antarctica spans 42 per cent of the continent.

The report warns China’s expanding presence in Antarctica is aimed at angling for resources including minerals, hydrocarbons, fishing, tourism, transport routes, water and bioprospecting.

The Antarctic plateau behind Australia’s Mawson base.

The Antarctic plateau behind Australia’s Mawson base.

“China has never stopped exploring Antarctic mineral resources, despite the requirements of the Madrid Protocol,” the report said.

Exploration activities have stepped up since 2012 including preliminary surveys of coal reserves and investigations of undersea metal deposits.

It’s in Australia’s national interest that Antarctica remains free from military competition, the report argues.

But in recent years China has frequently failed to accurately report the extent of its military’s activities in Antarctica as well as defence use of some of its scientific projects there, which is a breach of the Antarctic Treaty.

But in recent years China has frequently failed to accurately report the extent of its military’s activities in Antarctica as well as defence use of some of its scientific projects there, which is a breach of the Antarctic Treaty.

“China regards Antarctica as a useful laboratory for preparing for an advanced space program,” the report says.

“The engineering needed to build a modern research station in Antarctica can be applied in many other extreme environments, including space.”

“The engineering needed to build a modern research station in Antarctica can be applied in many other extreme environments, including space.”

Australia needed to urgently look at its funding priorities in Antarctica to protect its interests and encourage the Chinese to be more transparent about their polar policies.

“With careful diplomacy, a clear-headed strategy and leadership, and strategic investments in capacity, Australia can better manage its economic and political relationship with China while protecting its own national interests in Antarctica,” the report said.

“With careful diplomacy, a clear-headed strategy and leadership, and strategic investments in capacity, Australia can better manage its economic and political relationship with China while protecting its own national interests in Antarctica,” the report said.

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)