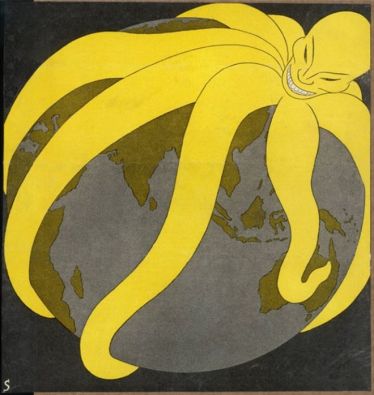

Many rogue states have resorted to limited land grabs designed to unilaterally change the territorial status quo before the target could muster an effective response. China is following this pattern.

by Lan D. Ngo

While the South China Sea has experienced a period of relative calm following HYSY-981 oil rig crisis in 2014, it is unclear whether the dispute would fully stabilize in the coming years, despite continuous efforts to negotiate a binding Code of Conduct.

Russia’s bolt-from-the-blue annexation of Crimea in early 2014 reminds states that their territories could be swiftly seized by an aggressive neighbor with territorial ambitions.

Therefore, claimants to the South China Sea dispute, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, should be prepared to deter a potential fait accompli, especially when modern history shows that states increasingly choose fait accompli rather than brute force to conquer new territory.

The Logic of Fait Accompli

States that seek to expand their territories have three basic options:

(i) brute force,

(ii) coercion, or

(iii) fait accompli.

In a brute force scenario, the aggressor first defeats the target state on the battlefield and then makes territorial demands.

Defeated militarily, the target state has no choice but to acquiesce to the victor’s demands. Alternatively, the aggressor could coerce the target to give up some of its territories.

Facing coercive pressures and in some cases, the looming threat of war, the target may decide that it would be better off acceding to the demands of the aggressor rather than risking escalation.

The problem with brute force is that it tends to be very costly in blood and treasure.

Even the weakest victims would fight back if their survival is truly at stake.

Hence a deliberately short war could quickly turn into an inextricable morass.

This is why brute force may be the only option when the aggressor seeks to conquer another state’s entire territory but makes little sense in the pursuit of limited territorial goals.

Coercion is less costly than brute force, but its track record is rather dismal, especially when the coercive demand involves territory.

Furthermore, by coercing the target, the aggressor inevitably reveals its intentions, thus giving an early warning to the target which may then engage in military preparations to blunt a possible first-strike advantage.

In other words, coercion is an ineffective tool of territorial conquest that would also reduce the range of options available to the aggressor to achieve its territorial goal.

This is why many states have resorted to fait accompli, i.e. limited land grabs designed to minimize risks of escalation.

A fait accompli allows the aggressor to unilaterally change the territorial status quo before the target could muster an effective response.

This forces the target into a tough position as it must choose between two unappealing choices:

(i) try to dislodge the invaders from the seized territory and risk escalation or

(ii) accept the territorial loss.

Every time an aggressor resorts to fait accompli, it is betting that the territorial loss for the target is small enough that it would rather give up than fight back and risk a larger conflict.

This is why decisiveness and limited scale are intrinsic features of every fait accompli.

While any fait accompli only directly involves two states, it usually has significant implications for third parties.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea is a territorial loss only for Ukraine, but the United States and other European countries are rightly concerned about the broader implications of Russia’s land grab. European leaders could be forgiven for believing that Crimea was just the first act and that Russia’s westward expansion would not stop in Ukraine.

Even if they can be absolutely certain of Moscow’s limited territorial appetite, many states still have strong incentives to reverse Russia’s fait accompli because failing to do so could embolden countries that also seek territorial expansion.

Yet fait accompli is a tactic designed to deter external intervention.

Brute force and coercion unfold over a lengthier period of time that allows third parties like the UN or a great power to intervene.

By rapidly changing facts on the ground, the aggressor could achieve its territorial goal before any third party could intervene.

Once faced with an accomplished fact, third parties could only intervene by attempting to roll back the aggressor’s territorial gains, which usually demands the use of force.

Since using force is costly and risky, third parties are less likely to intervene after the fait accompli had already occurred.

Thus a fait accompli usually aims at two targets simultaneously: the immediate victim and potential third party interveners.

In launching a fait accompli, the aggressor seeks to minimize two kinds of risk:

(i) risk of a protracted conflict (if the target fights back) and

(ii) risk of a broader conflict (if a third party intervenes).

After the Fact: Dealing with Territorial Loss after Fait Accompli

Assuming that states always seek to reclaim their lost territory over the long term, states facing a fait accompli have two basic options in the short term: they could immediately try to recapture the lost territory or they could wait for a more opportune moment to reclaim the lost territory in the distant future.

This decision, to respond immediately or delay, crucially hinges on two factors: the value of the contested territory and the visibility of the fait accompli.

A contested territory could be highly valuable for strategic and/or symbolic reasons.

A strategic territory usually offers immediate military advantages to the state that controls it.

The Crimean Peninsula with the Sevastopol naval base and the Strait of Malacca are examples of strategic territory.

Some territories are important because they hold symbolic importance, either because they are considered sacred grounds (e.g. Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif) or because they symbolize a larger power struggle (e.g. Berlin during the Cold War).

Leaders of a state facing the loss of a high-value territory should have strong incentives to immediately dislodge the invaders because losing such vital territory could endanger national security.

Even when security is not at stake, failing to immediately respond to such fait accompli could lead to severe political punishment as the people would not tolerate the loss of symbolically important territory.

This is why Ukraine immediately responded to recover Crimea after the Russian annexation in 2014.

What happens when the fait accompli targets a territory with little intrinsic value?

In such cases, leaders are likely to respond immediately only when the fait accompli is highly visible to the public audience.

When Argentina seized the Southern Thule island in 1976, the Callaghan government turned a blind eye toward the incident, even keeping the parliament and the British people in the dark for eighteen months before the fait accompli became public knowledge.

In contrast, when the Argentines seized the Falklands in 1982, Thatcher immediately appealed to the UN Security Council and dispatched the Navy across the Atlantic to recapture the islands.

Neither the Falkland Islands nor Southern Thule held much value in the eyes of British policymakers. The crucial difference here is that whereas Argentina stealthily took over Southern Thule, they publicly seized the Falklands.

Because the Falklands invasion was such a public event, it was a direct assault on British national honor and therefore humiliating.

Thatcher did not have any other choice than to respond immediately to Argentina’s fait accompli because failing to respond would have opened herself to attacks by her political rivals and precipitated the fall of her government.

Deterring a Fait Accompli in the South China Sea

Although China has not used military force to expand their territorial control in the South China Sea in recent years, this is no cause for complacent.

After all, China is the only claimant in the South China Sea dispute to have used force to seize islands controlled by other states.

They forcibly took the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam in 1974 and in 1988, the PLA Navy once again opened fire to seize control over a number of islands in the Spratlys controlled by Vietnam.

The 1995 Mischief Reef incident and more recently, the Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012 remind us that Beijing will resort to force when it finds no other way to enforce its claims in the disputed area.

The risk of a Chinese fait accompli in the South China Sea is also high because many factors play to its advantage.

Given the high level of asymmetric economic interdependence, China’s neighbors like the Philippines and Vietnam will pay an enormous cost for trying to recapture an island that China seizes. Furthermore, given the clear imbalance of power in favor of China, small countries are unlikely to resort to force to dislodge Chinese invading troops, lest the response provokes a larger and more devastating conflict.

The great power most capable of deterring Chinese adventurism in the South China Sea at this point is the United States.

Ideally, the United States would announce that it does not tolerate any attempt to solve the dispute by force, similar to its veiled deterrent threat against a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

However, this is unlikely to happen any time soon as U.S. behavior thus far shows that it lacks the resolve to directly challenge China in the South China Sea.

The best way to deter China from attempting a fait accompli, for the time being, is to convince Beijing that there is no possible way they could take the islands in a swift and bloodless fait accompli.

States increasingly rely on fait accompli rather than war or coercion because they believe it is a low-cost and low-risk alternative that could achieve similar territorial goals.

Consequently, fait accompli will become less attractive if those contemplating are convinced that the tactic actually carries more risk and costs than they previously believed.

Thus, states at risk of having their territories seized through fait accompli must convince the potential aggressors that they would definitely make an attempt to reclaim the lost territory, regardless of its intrinsic value.

To make this deterrent threat credible, leaders have to sacrifice policy flexibility and tie their hands by raising the public’s awareness about the disputed territories and therefore ensure strong public reaction should the disputed territories be invaded.

States should also garrison troops in territories that are vulnerable to a fait accompli.

In extreme cases, they could convince their own populace to inhabit the hitherto uninhabitable islands by supplying them with all necessary wherewithals to sustain a normal life on these islands.

These measures enhance the credibility of a retaliatory threat because it precludes the possibility of stealthily seizing a piece of territory.

More importantly, it ensures that leaders of target state must respond to the territorial challenge or risk losing power at home.