Revelations Liaoning fabricated statistics raise questions over rest of rust belt

By Lucy Hornby and Archie Zhang in Beijing and Jane Pong in Hong Kong

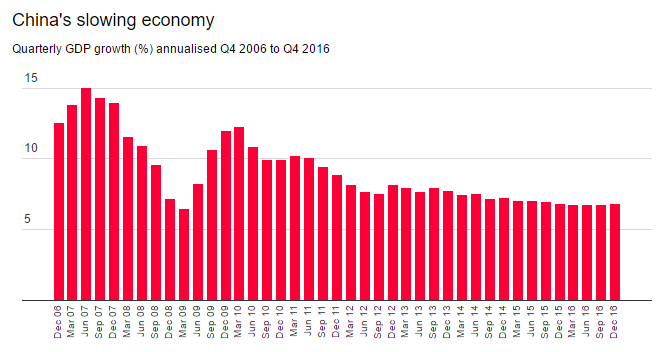

Sceptics about China’s economic statistics have taken a special pleasure in revelations of fake data in the north-eastern province of Liaoning dating at least to 2011.

Along with an officially reported contraction in its economy last year, they have given the impression that Liaoning’s economy is unusually troubled.

That impression may be unfair to Liaoning.

In 2007 when Li Keqiang was party secretary of Liaoning, he made waves when he declared China’s gross domestic product figures “man-made”.

Last week, even Xi Jinping weighed in on Liaoning’s data-faking, telling the province’s delegation to China’s annual legislative meeting that “the practice must be stopped”.

But is Liaoning the only province to have doctored its statistics?

The map below shows the share of metals and mining (a category that includes crude oil output) in the nominal gross domestic product of Chinese provinces in 2011.

China stopped publishing this data in 2012, the same year the commodity cycle turned sour.

The FT examined four provinces that are more reliant than Liaoning on the coal, steel and oil industries.

Shanxi, Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia comprise China’s coal heartland; Liaoning and Hebei together account for almost one-third of China’s steel output.

In regions where resources or steel dominate, the commodity cycle is more extreme.

Booms inflate the service sector, consumer spending and property prices; busts have an outsized effect on employment and government finances.

“China has a rust belt just like the US or UK,” says Andy Rothman, investment strategist at Matthews Asia.

Below are coal, oil and steel prices since 2010.

These benchmarks were multiplied by each province’s reported output of coal, oil and steel, and charted against the reported growth in GDP.

Below is Liaoning.

Strangely, when it admitted to a contraction in 2016, steel, coal and oil were already recovering.

The other provinces show a similar pattern in the three key industries.

Output values weakened in 2012, briefly recovered in the second half of 2013 and then took a deep dive.

Below is Hebei, home to one-quarter of Chinese steel production:

The worse period was the winter of 2015-2016, followed by a recovery in 2016, as seen below in Shaanxi...

and Inner Mongolia...

This pattern diverges from reported GDP figures, which show growth speeding up from early 2015. Below is Shanxi, the most mining-dependent of all Chinese provinces.

Metals and mining (mostly coal) made up 62 per cent of its industrial output in 2011 and 37 per cent of GDP.

Did Liaoning underperform last year, or were its reported data suddenly brought back in line with reality?

And what does that imply about the other rust-belt provinces?

“Liaoning is the most developed and diversified of the three north-eastern provinces, therefore it should have been performing better, not worse,” says Andrew Batson, economist at research group Gavekal Dragonomics.

In 2013 the Communist party pledged to implement a unified system for compiling provincial GDP. Rather than relying on provincial agencies to produce GDP figures in parallel with the national survey, the pledge called for the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing to take charge of the process. The goal was to avoid the perennial problem of provincial GDPs summing up to a higher number than the national figure.

NBS circulated a draft plan for the unified system in late 2014.

Ning Jizhe, director of NBS, told official media on Sunday that phase-in will begin in 2017 and be complete by 2020.

Observers must await the release of four years of corrected data from Liaoning — if indeed the true numbers are ever divulged — if they are to find out what really happened to northern China’s economy when the economic books were being cooked.