The New York Times

China has yet to give any details of the corruption charges against Meng Hongwei, the president of Interpol, who disappeared on a visit home and was later said to have been arrested.

Whatever the charges are, they are almost certainly not the real reason for his fate.

In China, the law is what the Communist Party says it is — more precisely, what Xi Jinping says it is.

And when an official of Meng’s global stature is nabbed, it’s a political decision — even if, coincidentally, he was corrupt, as is often the case in China.

Meng understood the rules of that game.

Meng understood the rules of that game.

He had been a vice minister of public security in a police state and had played a role in many operations, including Operation Fox Hunt, which tried to bring Chinese officials and businesspeople suspected of corruption back from abroad.

His former boss, Zhou Yongkang, was imprisoned for life on corruption charges in 2015.

Meng’s last WhatsApp message to his wife was an emoji of a knife, which she understood to mean he was in danger.

Interpol has asked Beijing for an explanation for Meng’s detention but has taken no further action.

Interpol has asked Beijing for an explanation for Meng’s detention but has taken no further action.

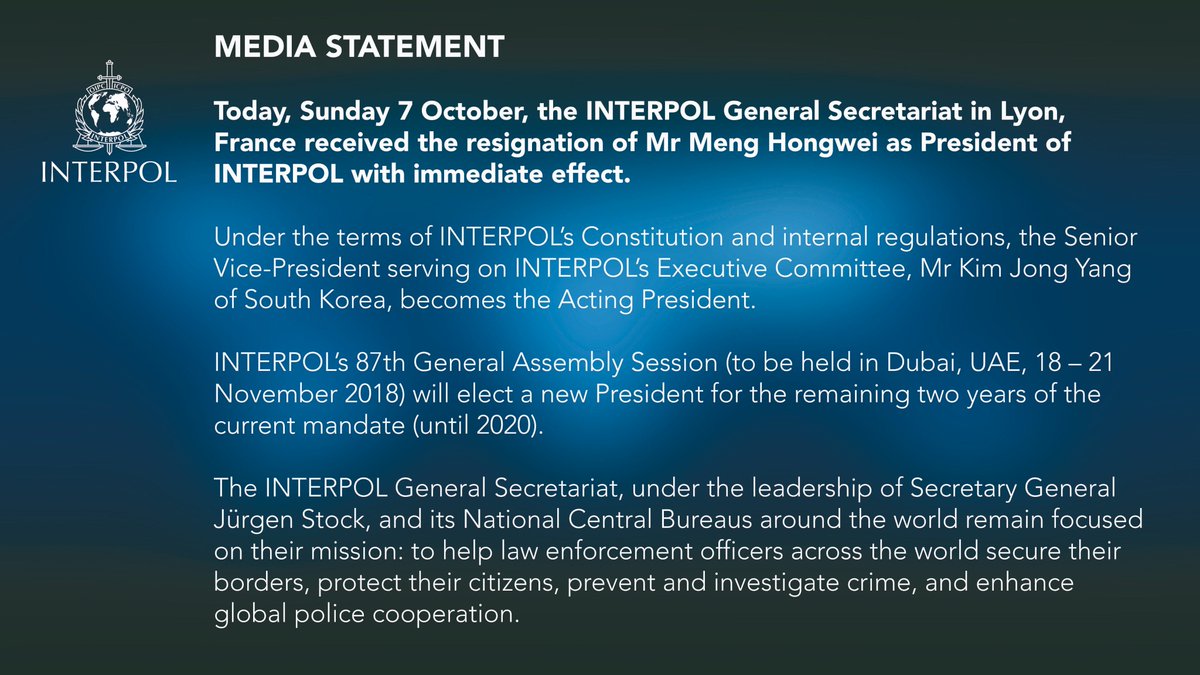

The agency issued a statement on Sunday that it had accepted his resignation as president “with immediate effect” and named a replacement.

Whatever else he was, Meng was the president of Interpol, a venerable international organization based in France that facilitates cooperation among police forces from its 192 member countries.

Whatever else he was, Meng was the president of Interpol, a venerable international organization based in France that facilitates cooperation among police forces from its 192 member countries.

The position of president is largely ceremonial — a secretary general, currently Jürgen Stock of Germany, runs day-to-day operations.

But the selection of a Chinese official for the post was a major feather in China’s cap, proudly hailed by Xi a year ago as evidence that China “abided by international rules.”

The crude arrest of Meng proclaims the opposite.

The crude arrest of Meng proclaims the opposite.

China’s behavior puts it more closely in a league with Russia, another nation whose authoritarian leader is convinced that his country is due global respect and deference by virtue of its wealth and might, and not its actions.

Tellingly, both China and Russia have brazenly tried to use Interpol to pursue political foes.

China put out a “red notice,” in effect a wanted alert, for Dolkun Isa, a self-exiled activist for the rights of China’s beleaguered Uighur minority.

Russia tried to use Interpol to catch Bill Browder, a hedge-fund manager turned anti-Vladimir Putin campaigner, among other political gadflies.

In these cases, Interpol has properly refused to cooperate.

It is possible that Meng’s failure to pursue the Isa warrant fed Xi’s anger.

It is possible that Meng’s failure to pursue the Isa warrant fed Xi’s anger.

According to The Economist, a Ministry of Public Security statement condemning Meng’s alleged wrongdoings also stressed the need for “absolute loyalty” and for “resolute support” for the country’s leader.

What Meng did to join the lengthening list of officials purged by Xi may never be fully known outside the Communist hierarchy.

What Meng did to join the lengthening list of officials purged by Xi may never be fully known outside the Communist hierarchy.

What is known, and deeply troubling, is how brazenly China is prepared to wage its internal power struggles without any regard for procedures, appearances or international norms.