by Xiaomei Chen in Xi'an

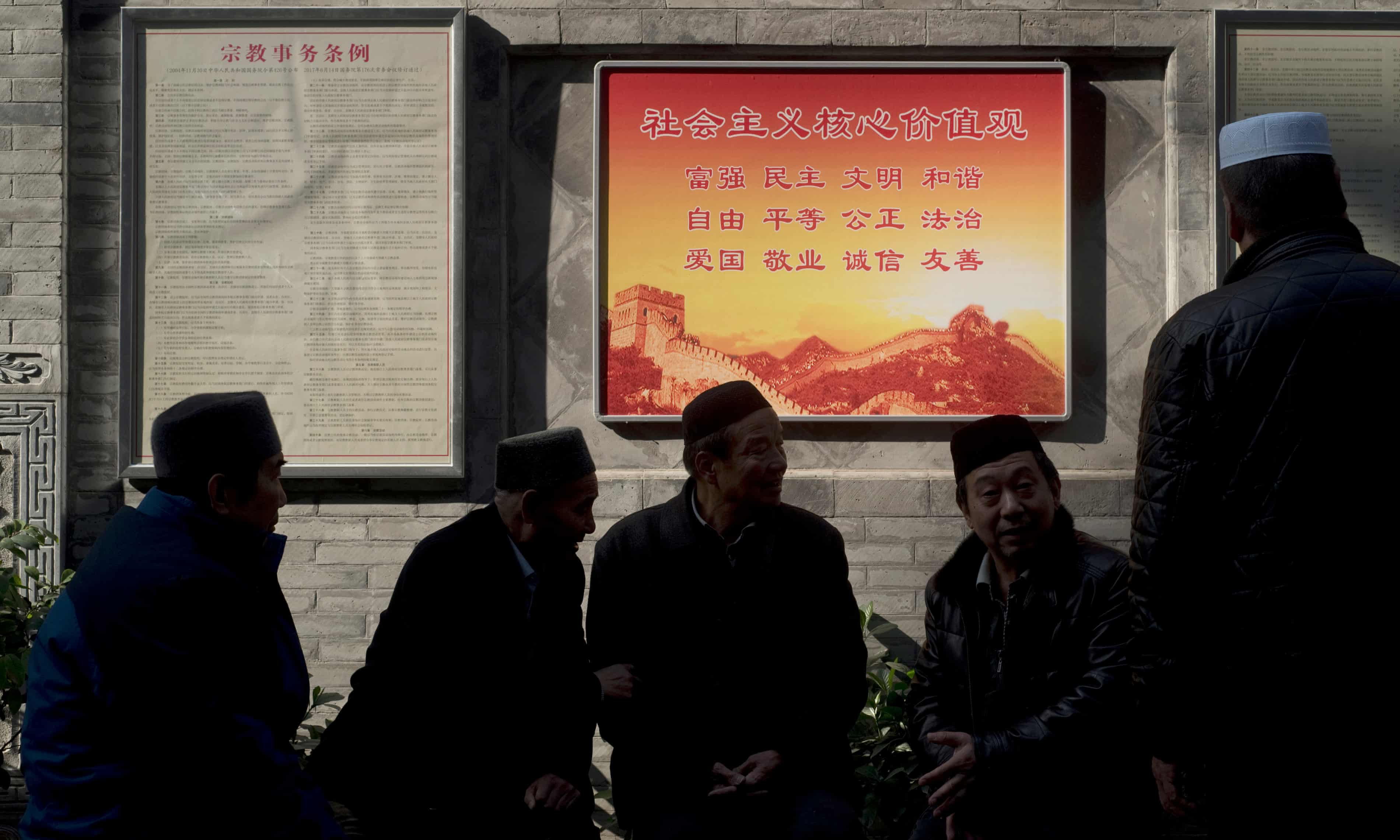

A political poster promotes ‘socialist values’ between lists of religious regulations at Xiaopiyuan Street Mosque in Xi’an’s Muslim quarter.

The streets of Xi’an’s Muslim quarter are bustling.

Tourists from all over China and the rest of the world throng the small stalls and restaurants for delicacies such as yangrou paomo lamb stew, roujiamo lamb burgers, persimmon cakes and “smoked ice-cream” – a bowl of puffed cereal dipped in liquid nitrogen.

There has been a Muslim community in the capital of Shaanxi Province – at the eastern end of the old Silk Road in central China – since the seventh century.

There has been a Muslim community in the capital of Shaanxi Province – at the eastern end of the old Silk Road in central China – since the seventh century.

During the Tang dynasty, when the city was called Chang’an, travelling Muslim merchants and some soldiers from central and west Asia made it their home.

Many married Chinese Han women, and their offspring became known as Hui, now one of China’s 56 ethnic groups.

The Muslim quarter is well-known for its range of halal and non-halal food stalls

In 2019, as the population of the wider city nears the 10 million mark that would define it as a “megacity”, the Muslim population is estimated at around 65,000.

Most live and work in the Muslim quarter, in the centre of historical Xi’an.

Life is good here.

Life is good here.

Restaurants and stalls boast of being featured on China Central Television, the state broadcaster, in programmes such as A Bite of China.

Many visitors come for the halal food, the most well-known example of which is yangrou paomo. Diners tear mo bread into pieces and then watch the chef churn it into the lamb soup.

Roujiamo is another famous halal dish – a burger made from juicy shredded braised lamb and crispy baked bread.

Then there are the wide, thick and incredibly filling biangbiang noodles – perfect for cold winter days.

Then there are the wide, thick and incredibly filling biangbiang noodles – perfect for cold winter days.

In the summer, liang pi is popular (cold rice noodles served in a sauce of chilli oil, pepper powder, vinegar and diced garlic, garnished with bean sprouts and sliced cucumber), as is pomegranate juice – sweet, sour and cool.

The entrance to Xiyangshi Street in the Muslim quarter

But non-Muslim snacks such as Hunan stinky tofu, Hubei roasted potatoes and barbecued squid and octopus are increasingly available too.

More and more shops now sell typical souvenirs from Shaanxi – such as leather shadow-play puppets and replicas of Qin terracotta warriors and horses.

There are also plenty of the kind of generic Chinese gifts that can be bought in any Chinese tourist town, most of them made in the manufacturing hub of Yiwu: Che Guevara T-shirts, cigarette containers featuring Mao Zedong, Buddhist prayer beads, you name it.

There are also plenty of the kind of generic Chinese gifts that can be bought in any Chinese tourist town, most of them made in the manufacturing hub of Yiwu: Che Guevara T-shirts, cigarette containers featuring Mao Zedong, Buddhist prayer beads, you name it.

Caricature street artists do a roaring trade as well.

Shops and stalls sell everything from spices and stinky tofu to souvenirs for tourists

Behind the story of booming business lurks an old fear – the precarious situation of being Muslim in China, especially given the reports of anti-"terror" crackdowns and political re-education camps in the majority-Muslim region of East Turkestan, more than 1,000 miles to the north-west.

“You can’t be too careful,” says one Chinese Muslim Hui I meet through a former colleague, and who does not want to be named in the international media.

“You know the situation in East Turkestan? We don’t want that in Xi’an!”

A souvenir shop.

During Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, religious practices and rituals were banned, and mosques were repurposed as factories, administration offices or community centres.

The 14th-century Great Mosque in Xi’an was temporarily turned into a factory to produce steel, and the 300-year-old Bei Guangji Street Mosque became the city’s cultural centre and sports hall.

Many here credit the economic liberalisation under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s with the Muslim quarter’s resurgence.

Many here credit the economic liberalisation under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s with the Muslim quarter’s resurgence.

Many Hui people I talk to speak of cleaner streets, renovated houses and better business opportunities.

Top left and main: Xiaopiyuan Street Mosque; top right: inside Daxuexi Alley Mosque

Recently, though, change is making people nervous.

The old bilingual signs in Arabic and Chinese at the entrances to the Muslim quarter have been replaced with new ones that only feature Chinese characters.

A senior committee member at one of the city’s largest mosques – who also asked not to be named – says local party officials asked him to introduce a ceremony to raise the Chinese national flag.

He refused, but agreed to display a flag at the mosque and put up several political posters.

He was also asked to discontinue the Muslim summer school.

The police warned him against “East Turkestan terrorists”, he says.

The mosque official is alarmed by news that authorities in Weizhou attempted to demolish its Grand Mosque last summer, but has faith that China’s constitution will “guarantee freedom of religion”.

The mosque official is alarmed by news that authorities in Weizhou attempted to demolish its Grand Mosque last summer, but has faith that China’s constitution will “guarantee freedom of religion”.

“I don’t think the order came from central government,” he says.

“It was some local official’s creative execution of our religious policies.”

A courtyard inside Xiaopiyuan Street Mosque

Leaving the mosque, I see the sign at the entrance to the Muslim quarter – right behind the Parkson shopping mall with its Adidas sportswear, L’Oréal shop and Chow Tai Fook jewellery.

The Arabic characters have indeed disappeared.

At the gate of another mosque I spot two red Chinese national flags.

Inside, the ancient grey brick walls now display glossy political posters.

“Like Cultural Revolution,” grunts one Hui man as he leaves the prayer hall.

Back on Xiyangshi food street, Aisha Ma is selling mahua, a kind of fried dough twist.

Back on Xiyangshi food street, Aisha Ma is selling mahua, a kind of fried dough twist.

She warns me against negative rumours about Muslims.

“You shouldn’t believe them,” she says.

“Here in China, we Hui people are peaceful. Look around, life has never been better.”

A few months ago, the old bilingual signs in Arabic and Chinese at the entrances to the Muslim quarter were replaced with new ones that only feature Chinese characters

She pauses.

A few months ago, the old bilingual signs in Arabic and Chinese at the entrances to the Muslim quarter were replaced with new ones that only feature Chinese characters

She pauses.

“Country comes first, then family,” she adds – a communist propaganda slogan that has been used in songs and patriotic speeches for decades.

A young Hui man selling barbecued squid on the stall next to hers echoes her words: “Country comes first, then family.”

They repeat the slogan in unison twice more, as if to reassure themselves.

A young Hui man selling barbecued squid on the stall next to hers echoes her words: “Country comes first, then family.”

They repeat the slogan in unison twice more, as if to reassure themselves.