The Economist

LAST year’s big blockbuster in China, “Wolf Warrior 2”, assured citizens not to fear running into trouble abroad: “Remember, the strength of China always has your back!”

LAST year’s big blockbuster in China, “Wolf Warrior 2”, assured citizens not to fear running into trouble abroad: “Remember, the strength of China always has your back!”

That is doubtless a comfort to patriots.

But for those who seek to escape the government’s clutches, its growing willingness to project its authority beyond its borders is a source of alarm.

In pursuit of fugitives, the Chinese authorities are increasingly willing to challenge the sovereignty of foreign governments and to seek the help of international agencies, even on spurious grounds.

Fugitives from China used to be mainly dissidents.

Fugitives from China used to be mainly dissidents.

The government was happy to have them out of the country, assuming they could do less harm there. But since Xi Jinping came to office in 2012 and launched a sweeping campaign against corruption, another type of fugitive has increased in number: those wanted for graft.

Though they do not preach democracy, they pose a greater threat to the regime.

Most are officials or well-connected business folk, insiders familiar with the workings of government. And in the internet age it is far easier for exiles to maintain ties with people back home.

So China has changed its stance, and started to hunt fugitives down.

So China has changed its stance, and started to hunt fugitives down.

It has managed to repatriate nearly 4,000 suspects from some 90 countries.

It has also recovered about 9.6bn yuan ($1.5bn).

Still, nearly 1,000 remain on the run, according to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, China’s anti-graft watchdog

The problem is that only 36 countries have ratified extradition treaties with China.

The problem is that only 36 countries have ratified extradition treaties with China.

France, Italy, Spain and South Korea are among them, but few other rich democracies.

It is easy for Chinese suspects seeking refuge abroad to argue that they will not get a fair trial if returned home, since the government does not believe that courts should be independent.

Last year the country’s top judge denounced the very idea as a “false Western ideal”.

What is more, China has thousands of political prisoners.

Torture is endemic.

The hard way

These failings have forced the Chinese authorities to resort to less-straightforward methods to bring suspects home.

The hard way

These failings have forced the Chinese authorities to resort to less-straightforward methods to bring suspects home.

Typically, they send agents, often travelling unofficially, to press exiles to return.

The tactics involved are similar to ones used at home to induce people to do the Communist Party’s bidding.

Many are subjected to persistent surveillance, intimidation and violence.

Occasionally, Chinese agents attempt to kidnap suspects abroad and bring them home by force.

If runaways have family in China, those left behind are often subject to threats and harassment.

If runaways have family in China, those left behind are often subject to threats and harassment.

In an interview in 2014 a member of Shanghai’s Public Security Bureau said that “a fugitive is like a flying kite: even though he is abroad, the string is in China.”

Exiles are told that their adult relatives will lose their jobs and that their children will be kicked out of school if they do not return.

Police pressed Guo Xin, one of China’s 100 most-wanted officials, to return from America by preventing her elderly mother and her sister from leaving China, and barring a brother living in Canada from entering the country, among other restrictions.

In the end she gave in and went home.

In countries with closer ties to China, agents have occasionally dispensed with such pressures in favour of more resolute action.

In countries with closer ties to China, agents have occasionally dispensed with such pressures in favour of more resolute action.

Wang Dan, a leader of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, says that he and other exiled dissidents have long avoided Cambodia, Thailand and other countries seen as friendly to China for fear of being detained by Chinese agents.

The case of Gui Minhai, a Swede who had renounced his Chinese citizenship, suggests they are right to do so.

He was kidnapped by Chinese officials in Thailand in 2015 and taken to the mainland.

In a seemingly forced confession broadcast on Chinese television, he admitted to a driving offence over a decade earlier.

Many countries, naturally, are upset about covert actions by Chinese operatives on their soil.

Many countries, naturally, are upset about covert actions by Chinese operatives on their soil.

In 2015 the New York Times reported that the American authorities had complained to the Chinese government about agents working illegally in America, often entering the country on tourist or trade visas.

Foreign diplomats note that officials from China’s Ministry of Public Security travel as delegates of trade and tourism missions from individual provinces.

Chinese police were caught in Australia in 2015 pursuing a tour-bus driver accused of bribery. Though France has an extradition treaty with China, French officials found out about the repatriation of Zheng Ning, a businessman seeking refuge there, only when China’s own anti-graft website put a notice up saying police had successfully “persuaded” him to return to China.

The French authorities had not received a request for his extradition.

This pattern is especially disturbing since the anti-corruption campaign is used as an excuse to pursue people for actions that would not be considered crimes in the countries where they have taken refuge—including political dissent.

This pattern is especially disturbing since the anti-corruption campaign is used as an excuse to pursue people for actions that would not be considered crimes in the countries where they have taken refuge—including political dissent.

It beggars belief that the Chinese authorities would have worked so hard to capture Mr Gui, the kidnapped Swede, just to answer for a driving offence.

His real crime was to have published books in Hong Kong about the Chinese leadership.

By the same token, last year the Chinese embassy in Bangkok reportedly asked the Thai government to detain the wife of a civil-rights lawyer after she escaped over China’s south-western border.

Her only known offence was to have married a man who had the cheek to defend Chinese citizens against the state.

Increasingly, China is trying to use Interpol, an international body for police co-operation, to give its cross-border forays a veneer of respectability.

Increasingly, China is trying to use Interpol, an international body for police co-operation, to give its cross-border forays a veneer of respectability.

Interpol has no power to order countries to arrest individuals, but many democratic states frequently respond to the agency’s “red notices” requesting a detention as a precursor to extradition.

In 2015 China’s government asked Interpol to issue red notices for 100 of its most-wanted officials. To date, the government says half of those on the list have returned, one way or another.

Small wonder that Xi Jinping has said he wants the agency to “play an even more important role in global security governance”.

Since 2016 Interpol has been headed by Meng Hongwei, who is also China’s vice-minister of public security.

Since 2016 Interpol has been headed by Meng Hongwei, who is also China’s vice-minister of public security.

That year alone China issued 612 red notices.

The worry is that China may have misrepresented its reasons for seeking arrests abroad.

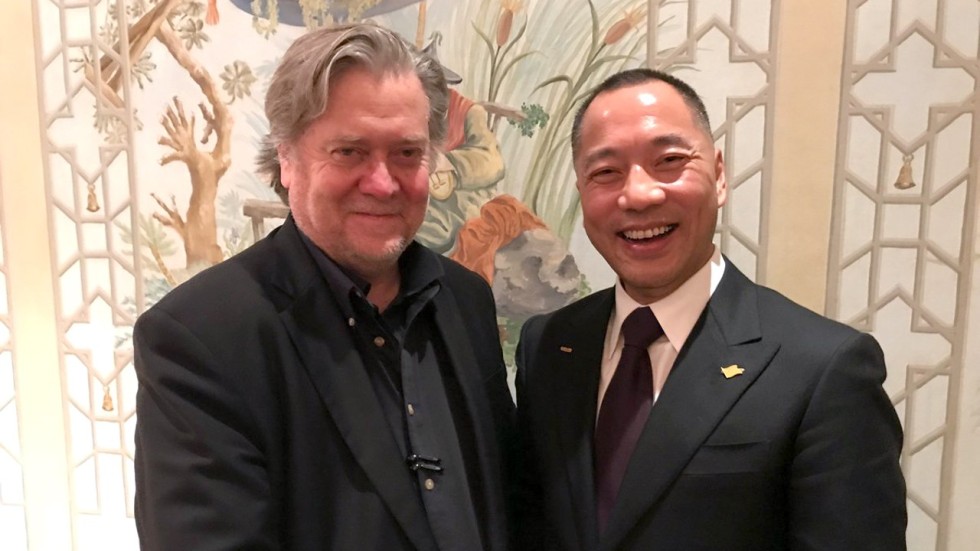

Miles Kwok, also known as Guo Wengui, a businessman who fled China in 2015, stands accused of bribery.

But it was only when he was poised to give an interview last summer in which he had threatened to expose the misdeeds of the ruling elite that China asked Interpol to help secure his arrest.

When America refused to send him home, the Chinese government requested a second red notice, accusing Mr Kwok of rape.

China’s covert extraterritorial activity suggests that foreign governments are right to be cautious about deepening ties in law-enforcement.

China’s covert extraterritorial activity suggests that foreign governments are right to be cautious about deepening ties in law-enforcement.

If nothing else, the fate of those who do return provides grounds for concern.

Although few would shed any tears for corrupt tycoons or crooked officials, the chances of any of them getting a genuine opportunity to prove their innocence are all but zero.

Nearly half of the repatriated officials who were subject to red notices have been sentenced to life in prison; the other half have not yet been tried.

Chinese courts have an astonishingly high conviction rate.

In 2016, the latest year for which figures are available, it was 99.9%.