China Has Also Been Targeting Turkish Nationals In Its Brutal Crackdown On Muslims

Turkey is the only Muslim country to call out China’s crackdown on Uighur Muslims. Our investigation finds that several Turkish nationals have also disappeared, something that has never been publicly acknowledged by Turkey.

By Megha Rajagopalan and K. Murat Yildiz

A baker prepares bread for display in a Uighur bakery in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul.

A baker prepares bread for display in a Uighur bakery in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul.

ISTANBUL — It was supposed to be a routine business trip, so the young Turkish man was surprised when immigration officials at the Chinese airport pulled him into a room and questioned him for hours.

He asked to speak to diplomats from his home country, but the Chinese officials shrugged their shoulders, telling him to take it up with police.

When police brought him in handcuffs to a jail cell on the other side of the country, so damp and dark that he immediately became sick, the man asked again.

They told him his Turkish passport, whose edges had worn out from use, was fake.

A week later, with his arms and legs shackled to a chair in an underground interrogation room in the city of Ghulja in western China, where he had lived before he became a naturalized citizen of Turkey, he asked for a third time to speak to Turkish diplomats.

This time the answer came sharp and clear.

“You are not a Turk,” an officer told him.

“You are from here. Don’t think you are special — we kill people like you so that others can live in peace.”

The young businessman said he had endured 38 days of interrogations, hunger, sleep deprivation, and abuse in Chinese custody before finally being released and deported back to Istanbul, without ever being told of any charges against him.

He is an ethnic Uighur — a religious and cultural minority group that the Chinese government views as a threat to the country’s security.

BuzzFeed News has found that six Turkish nationals — and possibly dozens more — have gone missing in China’s East Turkestan colony, including a pair of young children.

None of their cases have been publicly acknowledged by the Turkish government, and are being reported here for the first time.

Their families believe they have been sent to prisons or concentration camps, or in the case of the children, to state-run orphanages.

The families’ claims have been corroborated by email correspondence with government officials and copies of Turkish identification documents.

Every family interviewed by

BuzzFeed News said

Turkish authorities had given them little information on the status of their relatives, and that they had no evidence that their loved ones had ever been allowed to speak to Turkish diplomats — a privilege guaranteed to both prisoners and detainees by the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, to which China is a signatory.

None of the six people hold dual citizenship with China, according to their families.

Three other families contacted by BuzzFeed News said they also had relatives who were Turkish nationals who had gone missing in East Turkestan, but declined to speak further or be identified because of the sensitivity of the cases.

And three different Uighur community leaders in Istanbul said dozens more Turkish nationals have gone missing in East Turkestan, but BuzzFeed News could not independently verify all of these cases or speak to the families of those involved.

The families' stories show that Chinese authorities have been unafraid to sweep up foreign nationals in their campaign against Turkic Muslims, even people from countries that are important diplomatic partners.

The businessman who had spent more than a month in Chinese custody over the summer of 2017 became a Turkish citizen in 2011, giving up his Chinese citizenship, and was traveling in China on a tourist visa using his Turkish passport.

“At first I wasn’t that scared,” he said, neatly dressed in a black blazer and sporting a close-cropped haircut at a popular Uighur restaurant in Istanbul last month.

“I told my cellmates I’m a Turkish citizen, and sooner or later they’d release me.”

The businessman, who asked his name not be used because he is afraid Chinese authorities will retaliate against his family there, was only released after weeks of interrogations about his contacts in Turkey

and pictures he had shared on Facebook.

But the Turkish government, like many others in the world, went mostly quiet on the issue, as Turkey and China established closer economic and diplomatic ties.

That changed in February this year, when Turkey

issued the strongest statement in years through its foreign ministry, condemning the use of “concentration camps” by China.

In its unusual rebuke,

the foreign ministry called China’s treatment of Uighurs a “shame for humanity.”

But it said nothing about its own citizens who have been sent to internment camps without charge or who have been missing, in some cases, for more than a year.

In the cases of disappearance confirmed by BuzzFeed News for this article, families said they have contacted the Turkish foreign ministry as well as the presidency, members of parliament, and the Turkish embassy and consulates in China; been assigned case numbers; and been told the ministry is working to find out more information about their missing relatives.

But they have become distraught.

After months of begging the Turkish government for information, there have been few responses and no real news on the fates of their children, parents, and siblings.

Amid constant

news reports of detainees facing torture, hunger, and abuse in Chinese internment camps, the lack of information has been terrifying.

The Turkish foreign ministry was asked whether dozens of Turkish nationals had gone missing in China, and if so why it had not said anything about the issue publicly, what Turkey was doing on behalf of the individuals and their families, and to respond to comments from the families that they had heard little from the Turkish authorities.

The ministry did not comment by the time of this article’s publication.

The Chinese embassy in Turkey also did not respond to a request for comment.

The main street in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul, the unofficial center of the city's Uighur diaspora.

Turkey is home to one of the world’s largest Uighur diasporas, with a population of between 20,000 and 50,000 people,

The main street in the Zeytinburnu district of Istanbul, the unofficial center of the city's Uighur diaspora.

Turkey is home to one of the world’s largest Uighur diasporas, with a population of between 20,000 and 50,000 people, according to Uighur community leaders there.

Uighurs share close cultural, historical, and linguistic ties with Turkish people, and the public there is broadly sympathetic to Uighurs.

Protests

have broken out in Turkey as recently as 2015 over news of mistreatment of Uighurs in China and over forcible repatriation of Uighur migrants.

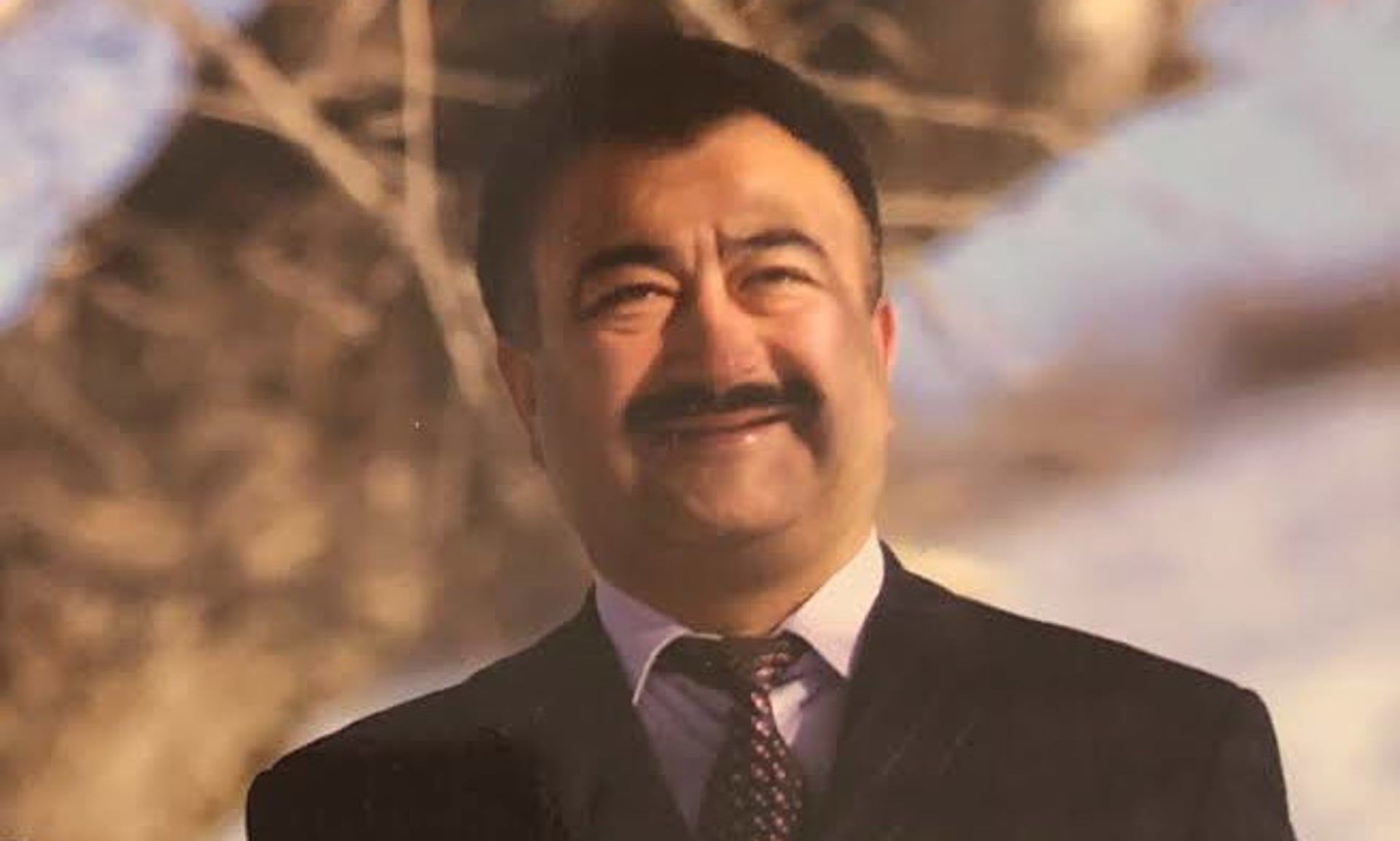

More recently, there was a public outcry in Turkey after reports in February of the death of Uighur folk musician

Abdurehim Heyit, whose music is popular in Turkey.

It was after this that the Turkish foreign ministry issued its

strong statement calling for China to close the camps.

“This tragedy has further reinforced the reaction of the Turkish public opinion towards serious human rights violations committed in the East Turkestan colony,” the statement said.

Heyit later appeared in a video released by Chinese state media saying he was in good health, sparking a

Twitter hashtag campaign by overseas Uighurs calling for displays of proof of life for their own family members.

The Uighur community in Turkey has been the heart of the exiled movement for the independence of East Turkestan — the name of the independent state some Uighurs hope to establish as their homeland — since the Communist party took power in China in 1949 and a group of Uighur leaders migrated to Turkey, said

Erkin Emet, an associate professor of language at Ankara University who is himself an ethnic Uighur and has researched the history and culture of Uighurs.

“From China’s perspective, Turkey is the most dangerous place for Uighurs,” Emet said, “because of the common culture and history we share with Turks. It is also a place where, unlike in many other Muslim countries, we can easily form political parties and organizations.”

The center of this independence movement, Emet said, is still in Turkey.

Since the early days of its campaign,

the Chinese government has specifically targeted Uighurs with links to Muslim countries for detention.

That has included people who have worked or studied in Muslim countries, or even those who just have relatives living there.

In particular, China has seized on links to Turkey.

According to the Associated Press, Uighur activists and officials from Syria and China estimate at least 5,000 Uighurs at one time traveled to Syria to fight, many doing so via Turkey.

China has also said Uighur separatist militants were responsible for a wave of deadly knife and bomb attacks in 2013 and 2014 in East Turkestan and elsewhere in the country.

But China has targeted millions of Turkic Muslims in its crackdown, the overwhelming majority of whom have no proven links to any extremist cause.

The total number of foreign nationals swept up in the campaign against Muslim minorities, which includes ethnic Kazakhs, is not publicly known.

Many countries have preferred to advocate for their citizens through quiet diplomacy rather than public advocacy.

Three Australian citizens were

released last year after being detained in internment camps.

Australia is also now

working to secure the release of a Uighur Australian baby boy whose father believes he’s at risk of being sent to a state-run orphanage, in a case first reported by

BuzzFeed News.

Kazakhstan has remained publicly silent about the plight of ethnic Kazakhs in the region who have been swept up by China’s crackdown, although last August, a Kazakh court ruled against deporting

Sayragul Sauytbay — who had worked in an internment camp as a teacher and later fled to Kazakhstan — to China.

BuzzFeed News has shown how Uighurs in countries as far flung as Sweden, Australia, Turkey, and the United States have reported

facing harassment and intimidation from Chinese government agents who have contacted them through social media.

Several countries and multinational bodies, including the United States, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and the EU, have publicly condemned the Chinese government’s human rights abuses in the region, but

China’s incarceration campaign has not led to any international sanctions.

China does not consider the concentration camps to be a form of criminal punishment.

Government officials have said they are for "vocational training" and have

likened them to “boarding schools,” though escapees from the camps have

reported being forcibly taught Chinese language and party propaganda, and

subjected to hunger, stress positions, sleep deprivation, and other abuses.

But this puts families of detainees in a difficult spot because it means there is no arrest paperwork, no sentence, and frequently no communication at all from Chinese police.

It is as if their parents, siblings, or children have simply vanished.

And it’s unclear whether Chinese authorities have provided Turkish officials with any more information.

Hankiz Kurban and her younger sister Nurbiye Kurban in Istanbul.

Hankiz Kurban and her younger sister Nurbiye Kurban in Istanbul.

Hankiz Kurban was, like her three younger siblings, born and raised in Turkey, but has lived in China on and off for years, trying to make the family’s import and export logistics business a success.

For years the 28-year-old had lived in Urumqi, the regional capital of East Turkestan, with her mother, Amina, and her father, Yahya, to whom she had always been close.

A quiet, methodical man, 52-year-old Yahya would draw up a to-do list each morning before breakfast.

Because they planned to keep working in China, he was careful, Hankiz said.

He forbade her from getting involved in political causes, even in Turkey.

She went to a Uighur cultural event once when she was younger, and he scolded her.

Hankiz started taking Chinese lessons, hoping it would make it easier to work with business partners in China.

In 2017, she started hearing rumors of people who were disappearing.

Friends and neighbors told her about fathers and brothers who were taken away by police in the middle of the night.

Hankiz started to worry, but her father was unfazed.

After all, they were Turkish citizens, staying legally in China.

They paid taxes.

They had taken care to do everything aboveboard.

When Hankiz’s visa expired, she returned to Turkey to renew it.

This was already unusual, she said — in the past she could have done this within China.

While she was in Turkey, what she had feared the most happened.

Both of her parents were detained.

She found out through a final voice message from her mother.

“They’re taking us away,” she said in the message.

“Contact the embassy.”

“That was when our hell began,” Hankiz said.

Yahya and Amina Kurban were not the only family members to disappear.

Hankiz’s uncle, Mehmet Emin Nasir, 39, disappeared in Kashgar, a city in southern East Turkestan, on September 9, 2017.

“We never thought this would last so long. We thought that as a Turkish citizen, sooner or later he’d be released,” Muyesser Temel, Nasir’s sister and Hankiz’s aunt, said as she sat in a yellow armchair at her family’s home in the immigrant-heavy neighborhood of Zeytinburnu, where much of Istanbul’s Uighur community lives in apartment blocks.

“At the beginning I wasn’t scared, but as time passed I realized this was serious.”

Temel first heard that Nasir was taken away by police from her mother, who had gotten a phone call from relatives in East Turkestan.

Nasir, who ran a shop that sold curtains, was living in Kashgar with his wife and four children at the time.

He held a Turkish passport, but unlike many other Turkish Uighurs, he wanted to live in his homeland.

His wife never sought Turkish citizenship because the family was settled in East Turkestan.

Temel said she reached out to the Turkish foreign ministry through repeated phone calls for months since she discovered her brother had been taken away.

“They tell us they’re in touch with Chinese authorities, but we have no proof of it,” she said.

“They just tell us on the phone they are dealing with this, but there’s no evidence.”

“We trust above everything our country, Turkey,” she said.

“But nothing has come out of this. We have exhausted all of our options.”

Both women, and other individuals interviewed for this article, said they had received few signals from the Turkish foreign ministry about the status of their families, even when Turkish officials promised to help.

Even Turkish children have not been spared from China’s crackdown.

Pashahan Kuçar, 75, has two young grandchildren.

Both Turkish citizens who were traveling on their mother’s Chinese passport, they have disappeared in East Turkestan along with their mother, Kuçar's daughter-in-law.

According to their identification records, which her family provided to BuzzFeed News, Kuçar's granddaughter is 7 and her grandson has recently turned 6.

When their mother was taken away to an internment camp, the children were left alone.

A neighbor took them in and explained the situation to Kuçar's family by text.

But not long after, the neighbor stopped responding to messages.

Kuçar hasn’t heard from her grandchildren in months.

Though Kuçar can barely walk and suffers from several health conditions, she has relentlessly campaigned for the release of her family.

In Turkey’s capital, Ankara, she has protested outside the presidential palace on a mobility scooter, draped in the light blue flag of East Turkestan.

She has met with Turkish foreign ministry officials, but they’ve given her no clues about where her grandchildren are or whether Turkish diplomats have been able to contact them.

Pashahan Kuçar

Pashahan Kuçar

In a way, Temel, the woman whose home is in Zeytinburnu, counts her missing brother among the lucky.

The fact that he holds Turkish citizenship means at least she can expect Turkish authorities to help.

“You cannot find a family in this neighborhood that does not have family in the camps,” she said. “The internet is blocked over there; there’s no way to contact them — if my mother had not gotten that call we would simply not know.”

Hankiz Kurban, the 28-year-old who once dreamed of building a business in China with her father, has tried everything to find news on her missing parents.

She reported the matter to Turkish authorities and received a case number in an automated email.

She began calling the Turkish Embassy in Beijing every other day — so much that officials started to hang up when they heard her voice.

She lies awake at night obsessing about what might be happening to her father and mother.

She tried taking medication for her anxiety and depression, but it just made her feel sleepy and fuzzy. What she can’t figure out is how her father, who all his life eschewed political causes so as not to get on the wrong side of the government, could have been targeted.

Two years ago in Ghulja, interrogators asked the young businessman detained at the airport in China the same questions about his politics and connections over and over again, searching for evidence of his connections to extremist groups.

There were two interrogators, he said, one Han Chinese — China’s largest ethnic group — and the other Uighur, both fluent in the Uighur language.

One day they demanded his social media passwords — to Facebook, WhatsApp, and the Chinese messaging app QQ.

They found a post he had shared on Facebook showing both the Turkish flag and the flag for East Turkestan.

That day they became certain, he said, that he was a threat.

It was like they had discovered a smoking gun.

Another day they asked him to list his contacts in Istanbul, to tell them which Uighur restaurants he frequented.

He gave a list of made-up names, he said.

But the pair of interrogators knew the Uighur community in Turkey well.

Unlike many Uighurs in Istanbul, the businessman didn’t live in Zeytinburnu.

His interrogators knew the neighborhood’s shops and alleyways better than he did.

In the days before his departure, one of his interrogators mentioned he’d be traveling to Turkey in a few months.

“If you see us in Istanbul,” he said, “will you welcome us?” ●

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/D64TIFJAUNBVRCNC3T35TB63IQ.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/D64TIFJAUNBVRCNC3T35TB63IQ.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/3ZVN5DEOHVEAZFDFFWYEMVDQBA.jpg) Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar. Classified documents lay out the Chinese government's deliberate strategy to lock up ethnic minorities.

Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar. Classified documents lay out the Chinese government's deliberate strategy to lock up ethnic minorities. /arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/3ZVN5DEOHVEAZFDFFWYEMVDQBA.jpg) Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar. Classified documents lay out the Chinese government's deliberate strategy to lock up ethnic minorities.

Uighur security personnel patrol near the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar. Classified documents lay out the Chinese government's deliberate strategy to lock up ethnic minorities. /arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/FNAVX5BJPFEBJM72M64SDFPRFE.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/FNAVX5BJPFEBJM72M64SDFPRFE.jpg)