By ANTHONY KUHN

The front page of the Communist Party's flagship newspaper the People's Daily (center) and other papers are seen one day after the unveiling of the new Politburo Standing Committee in Beijing last year.

"A thousand newspapers with the same front page" is how the Chinese have for decades described the enforced uniformity of the country's state-controlled media.

Now, one face increasingly dominates those front pages.

It belongs to Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, who has gone to extraordinary lengths to control the narrative about China.

"The party controls the media, and of course, that means it controls the message," says University of Hong Kong media expert David Bandurski.

"The party controls the media, and of course, that means it controls the message," says University of Hong Kong media expert David Bandurski.

"And basically, Xi Jinping is the message."

That message has gotten mixed results.

That message has gotten mixed results.

Often, it's what China says, not what it does, that makes the deepest impression.

Nevertheless, it is a prime example of how shaping the world's perceptions of their country has climbed toward the top of the Chinese leadership's agenda.

The trend is evident, for example, at the China Daily, the country's top English-language newspaper, by circulation.

"Our motto used to be, 'Let China go out into the world; let the world understand China,' " says Bridget, a China Daily journalist.

The trend is evident, for example, at the China Daily, the country's top English-language newspaper, by circulation.

"Our motto used to be, 'Let China go out into the world; let the world understand China,' " says Bridget, a China Daily journalist.

"Now it's: 'Report on China; influence the world.'"

Bridget is one of several of the paper's journalists who spoke on the condition that they be identified only by their English first names, because they weren't authorized to speak to foreign reporters.

Another, named Gary, explains that no matter what's going on, Xi is always at the top of the news.

In fact, he says, that's a rule at the government's mobile news app, which China Daily runs.

"News of Xi Jinping always comes first, and Li Keqiang always comes second," he says.

Bridget is one of several of the paper's journalists who spoke on the condition that they be identified only by their English first names, because they weren't authorized to speak to foreign reporters.

Another, named Gary, explains that no matter what's going on, Xi is always at the top of the news.

In fact, he says, that's a rule at the government's mobile news app, which China Daily runs.

"News of Xi Jinping always comes first, and Li Keqiang always comes second," he says.

"That's not to say that they make news every day. But even if they don't, their news stays in the top two positions."

Another journalist, Miranda, says news about Xi is edited with extreme caution.

"If we can possibly avoid using his name, we do," she says, "because an error in an article related to Xi would have very serious consequences."

For the past two decades, Xi's predecessors appeared as stiff and colorless apparatchiks, aloof from the common folk.

Another journalist, Miranda, says news about Xi is edited with extreme caution.

"If we can possibly avoid using his name, we do," she says, "because an error in an article related to Xi would have very serious consequences."

For the past two decades, Xi's predecessors appeared as stiff and colorless apparatchiks, aloof from the common folk.

By contrast, Xi has cultivated a more three-dimensional image — of a forceful, visionary leader, who is also a down-to-earth man of the people.

One minute, state media trumpet Xi's achievements in building China into an economic powerhouse. The next, they show him holding an umbrella for his wife, Peng Liyuan.

One minute, state media trumpet Xi's achievements in building China into an economic powerhouse. The next, they show him holding an umbrella for his wife, Peng Liyuan.

Coverage goes into intimate detail about Xi's youth in the hardscrabble northwest of the country.

Some of Xi's earthy aphorisms have flooded social media and become popular mantras in Chinese society, such as: "We've gotta just roll up our sleeves and get down to work."

China Daily journalist Miranda says some of it seems to work on a domestic audience.

"The elder generation in my family and my classmates all have pictures of Xi and Peng on their walls," she observes.

But behind the celebrity-style coverage and crafting of Internet memes, Xi's use of the media has helped him to consolidate his political power to a degree not seen in China for decades.

Xi has "used social media accounts under his control to create a collective, subliminal message," argues independent analyst Wu Qiang.

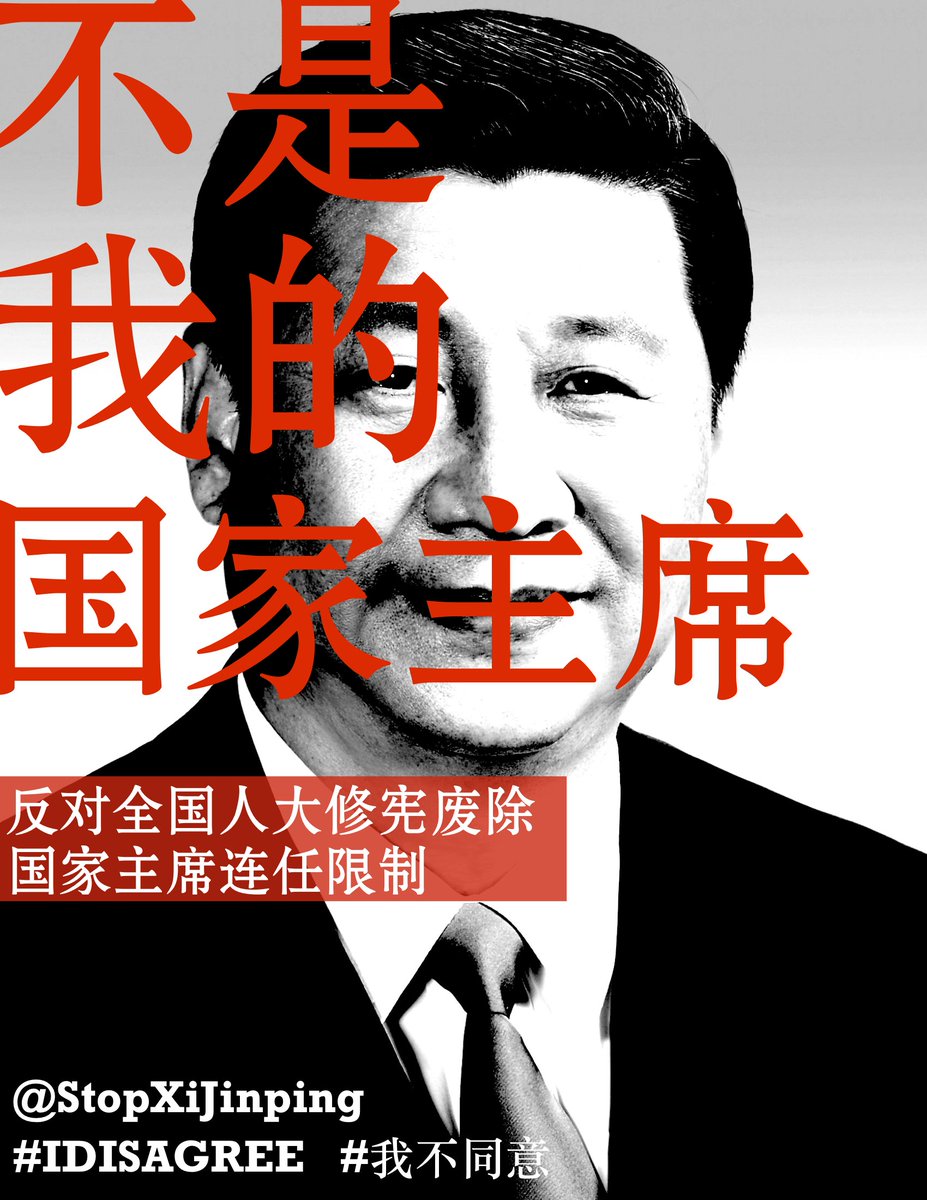

The narrative conveyed through state media, Wu continues, presented the public with a fait accompli: that Xi had succeeded in erasing presidential term limits from the constitution, allowing him, in theory at least, to rule indefinitely.

Some of Xi's earthy aphorisms have flooded social media and become popular mantras in Chinese society, such as: "We've gotta just roll up our sleeves and get down to work."

China Daily journalist Miranda says some of it seems to work on a domestic audience.

"The elder generation in my family and my classmates all have pictures of Xi and Peng on their walls," she observes.

But behind the celebrity-style coverage and crafting of Internet memes, Xi's use of the media has helped him to consolidate his political power to a degree not seen in China for decades.

Xi has "used social media accounts under his control to create a collective, subliminal message," argues independent analyst Wu Qiang.

The narrative conveyed through state media, Wu continues, presented the public with a fait accompli: that Xi had succeeded in erasing presidential term limits from the constitution, allowing him, in theory at least, to rule indefinitely.

Censors then scrubbed any trace of opposition to Xi's move from the Internet.

The University of Hong Kong's Bandurski contends that the media's obsessive focus on Xi, meanwhile, is displacing or erasing other important news, contributing to an information vacuum about China, just when the world can least afford it.

But, Liu Xiaoying, a media scholar at Communication University of China in Beijing, argues that China needs to focus on a main character to tell its story effectively and that Xi is that character.

China began taking its image-building very seriously well before Xi became president.

The University of Hong Kong's Bandurski contends that the media's obsessive focus on Xi, meanwhile, is displacing or erasing other important news, contributing to an information vacuum about China, just when the world can least afford it.

But, Liu Xiaoying, a media scholar at Communication University of China in Beijing, argues that China needs to focus on a main character to tell its story effectively and that Xi is that character.

China began taking its image-building very seriously well before Xi became president.

Liu traces it back to the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

He says that many Chinese felt that foreign media criticism of their pollution and human rights record spoiled their moment in the world spotlight.

"We felt our ability to transmit our views was inadequate," Liu explains. "We were unable to speak up."

Since then, China has poured billions of dollars into its state-run media, hiring journalists and public relations firms.

For example, the official Xinhua News Agency expanded its overseas bureaus from 100 a decade ago to about 180 as of 2015.

State broadcaster China Radio International, meanwhile, has grown to include coverage in 61 languages and puts out 2,700 hours of programming a day, according to the CRI website.

The message to these audiences, says Bandurski, is that China's rise is a boon to all nations.

The state-run media portray the country as a provider of public services and solutions to global problems.

"This is all about China's position in the world, in a sense, China's rightful position in the world, a kind of return to centrality for China," Bandurski says.

He says that many Chinese felt that foreign media criticism of their pollution and human rights record spoiled their moment in the world spotlight.

"We felt our ability to transmit our views was inadequate," Liu explains. "We were unable to speak up."

Since then, China has poured billions of dollars into its state-run media, hiring journalists and public relations firms.

For example, the official Xinhua News Agency expanded its overseas bureaus from 100 a decade ago to about 180 as of 2015.

State broadcaster China Radio International, meanwhile, has grown to include coverage in 61 languages and puts out 2,700 hours of programming a day, according to the CRI website.

The message to these audiences, says Bandurski, is that China's rise is a boon to all nations.

The state-run media portray the country as a provider of public services and solutions to global problems.

"This is all about China's position in the world, in a sense, China's rightful position in the world, a kind of return to centrality for China," Bandurski says.

"And this is all tied up with this important foreign policy of the Belt and Road."

More than 70 countries have signed on to participate in Xi's signature policy, aimed at building infrastructure, ports and roads linking the world to China.

Of course, China is hardly alone in its focus on its leader and his policies.

Maria Repnikova, a media expert at Georgia State University, says Xi has a lot in common with other leaders, from Russia's Vladimir Putin to Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

All of them, she says, use media to portray themselves as political strongmen and to put out nationalist and populist messages.

"There's kind of the highlight on the leader himself," Repnikova notes, "his style, his personality, humor, and the communication through various channels," including personal social media accounts.

This summer, though, Xi's messaging seemed to run into resistance.

More than 70 countries have signed on to participate in Xi's signature policy, aimed at building infrastructure, ports and roads linking the world to China.

Of course, China is hardly alone in its focus on its leader and his policies.

Maria Repnikova, a media expert at Georgia State University, says Xi has a lot in common with other leaders, from Russia's Vladimir Putin to Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

All of them, she says, use media to portray themselves as political strongmen and to put out nationalist and populist messages.

"There's kind of the highlight on the leader himself," Repnikova notes, "his style, his personality, humor, and the communication through various channels," including personal social media accounts.

This summer, though, Xi's messaging seemed to run into resistance.

This became apparent when authorities temporarily pulled a triumphal-sounding documentary called Amazing China.

The film credited Xi with transforming China into a global leader in technology.

But critics took to state media to blast the movie for exaggerating China's technical prowess, when in fact, they pointed out, China remains highly reliant on the United States for high-tech products.

Analyst Wu says such propaganda may have made Chinese officials overconfident that they could win a trade war against the U.S.

"China's leaders exaggerated the country's soft power so much so that they believed their own propaganda," he scoffs.

But critics took to state media to blast the movie for exaggerating China's technical prowess, when in fact, they pointed out, China remains highly reliant on the United States for high-tech products.

Analyst Wu says such propaganda may have made Chinese officials overconfident that they could win a trade war against the U.S.

"China's leaders exaggerated the country's soft power so much so that they believed their own propaganda," he scoffs.

"It took the trade war with the U.S. to poke a hole in their illusion."

Repnikova argues that China's story, and its example of high-speed economic growth, has found more receptive audiences in many developing countries.

"We should think about the broader picture, that many countries would still probably continue to see China as this strong global actor, and potential partner and investor," she says.

But Wu notes that China is having a harder time coming up with ideas that appeal to Western audiences.

That's partly because, Wu says, the Communist Party has publicly rejected universal values, which it argues don't fit China.

Xi "publicly opposes everything from civil society to freedom and democracy. That gives him very little room to express himself," he adds.

If China has alternatives to what the West considers universal values, it hasn't been clear about what they are.

Repnikova argues that China's story, and its example of high-speed economic growth, has found more receptive audiences in many developing countries.

"We should think about the broader picture, that many countries would still probably continue to see China as this strong global actor, and potential partner and investor," she says.

But Wu notes that China is having a harder time coming up with ideas that appeal to Western audiences.

That's partly because, Wu says, the Communist Party has publicly rejected universal values, which it argues don't fit China.

Xi "publicly opposes everything from civil society to freedom and democracy. That gives him very little room to express himself," he adds.

If China has alternatives to what the West considers universal values, it hasn't been clear about what they are.

China's centuries of political and philosophical traditions might contain some answers, but Beijing hasn't bothered to revive or explain them.

Western governments, meanwhile, have recently become more vigilant of Chinese state media as extensions of Beijing's political influence.

The U.S. Justice Department last month ordered Xinhua and the China Global Television Network to register as foreign agents.

Western governments, meanwhile, have recently become more vigilant of Chinese state media as extensions of Beijing's political influence.

The U.S. Justice Department last month ordered Xinhua and the China Global Television Network to register as foreign agents.