Chinese "fishing boats" around contested islands are part of an extensive maritime militia.

BY GREGORY POLING

The Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) Navy aircraft carrier

The Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) Navy aircraft carrier Liaoning

participates in a naval parade near Qingdao in eastern China's Shandong province, on April 23, 2019.

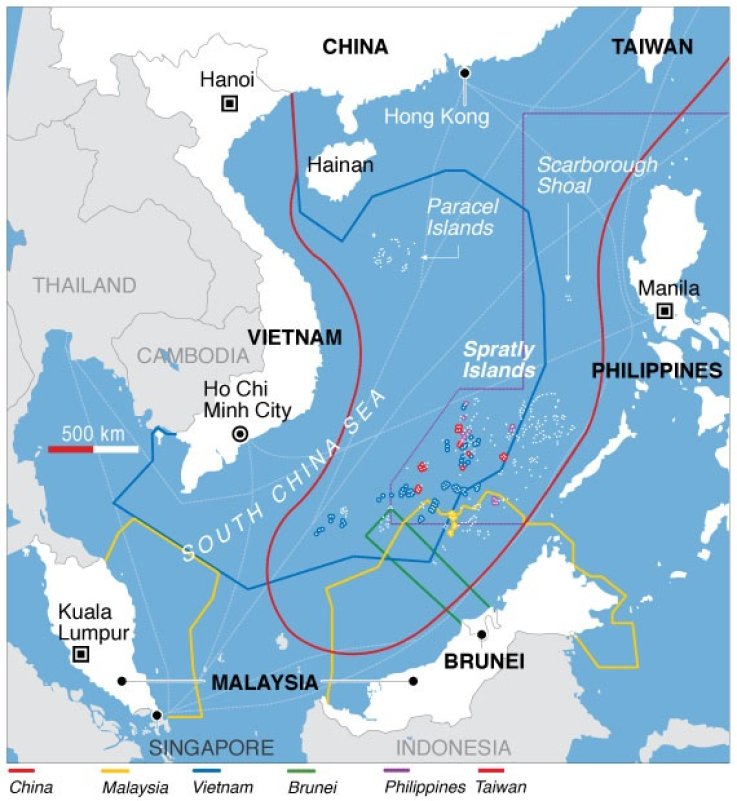

The Spratly Islands, occupied by five different claimants, are the most hotly contested part of the South China Sea.

Thanks to the harbors and supporting infrastructure Beijing constructed on its outposts there over the last five years, most vessels operating around the Spratlys are Chinese.

And most of those are at least part-time members of China’s official maritime militia, an organization whose role Beijing frequently downplays but that is playing an increasingly visible role in its assertion of maritime claims.

Writers affiliated with Chinese institutions and state media seek to present an alternate version of reality by artfully cropping satellite imagery, cherry-picking data, or simply ignoring the facts and attacking the motives of those presenting evidence of militia activities.

This is unsurprising—

the purpose of employing a maritime militia is to keep aggression below the level of military force and complicate the responses of other parties, in this case chiefly the other claimants (Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Taiwan) as well as the United States,

by hiding behind a civilian facade.

Without deniability, the militia loses much of its value.

That gives China a strong incentive to dissemble and deny evidence of its actions.

But that evidence speaks for itself.

The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia is

not a secret.

Article 36 of the China Military Service Law of 1984, revised in 1998, calls for the militia “to undertake the duties related to preparations against war, defend the frontiers and maintain public order; and be always ready to join the armed forces to take part in war, resist aggression and defend the motherland.”

China’s 2013 defense white paper enhanced the maritime militia’s role in asserting sovereignty and backing up military operations.

This is the naval analogue to China’s larger and better-known land-based militia forces, which operate in all Chinese theater commands, supporting and under the command of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

In 2013, Chinese dictator

Xi Jinping visited the maritime militia in Tanmen township on Hainan, China’s southernmost province, and labeled it a model for others to follow.

Andrew Erickson, Conor Kennedy, and Ryan Martinson at the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College have spent years

documenting the activities of the maritime militia, including

extensive acknowledgment by Chinese authorities and many instances in which militia members have publicly discussed their activities.

A review of available

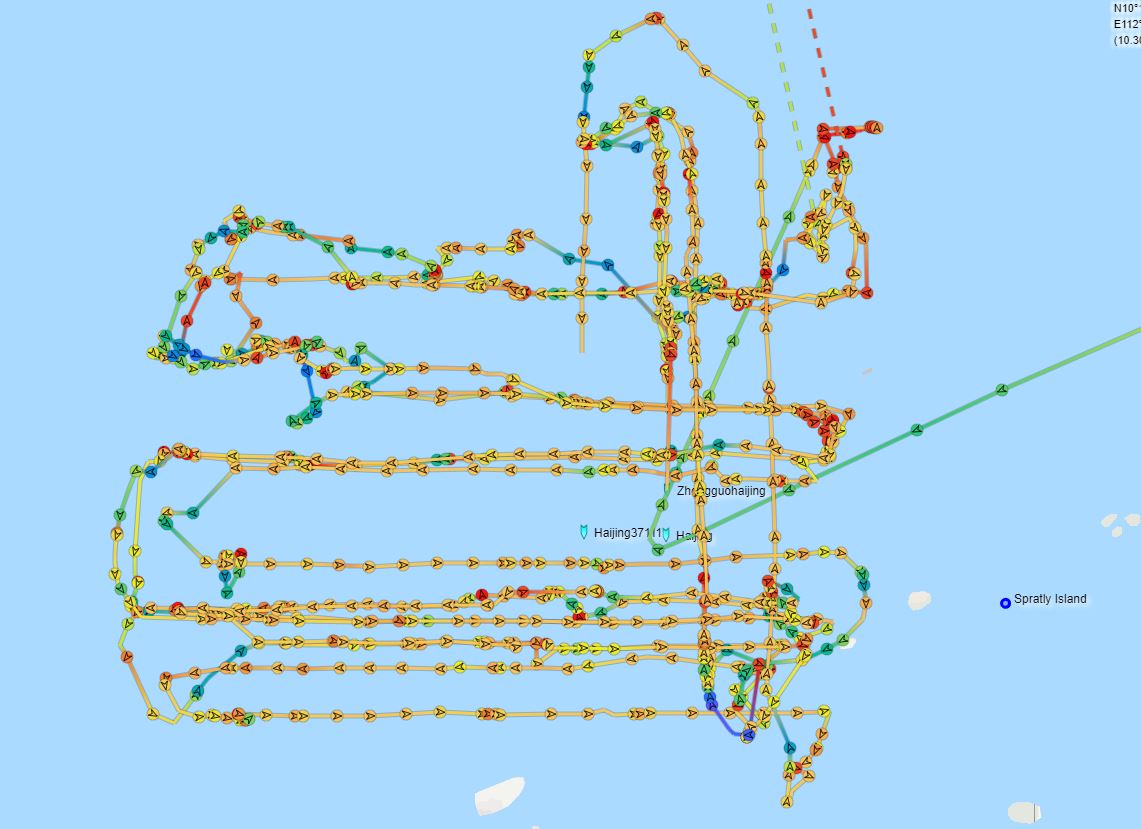

remote sensing data by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and Vulcan Inc.’s Skylight Maritime Initiative, including infrared imaging, synthetic aperture radar, and high-resolution satellite imagery, shows that

the largest number of vessels operating in the Spratly Islands belongs to the Chinese fishing fleet, which frequently numbers between 200 and 300 boats at Subi and Mischief Reefs alone.

This is not by itself peculiar: China maintains the world’s largest fishing fleet, and its distant water vessels operate around the globe due to overfishing and pollution of Chinese coastal waters.

But the vessels operating in the Spratlys are not part of that distant water fleet—those boats are larger and head farther afield in the hunt for high-value migratory species.

And at 800 nautical miles (about 920 miles) from the mainland, the Spratlys are too far for small and medium-sized Chinese fishing vessels to operate productively without being heavily subsidized.

But even China’s two-decade-old policy of subsidizing fishing as an assertion of sovereignty can’t explain the behavior of most Chinese vessels in the Spratlys in recent years.

Chinese fishing boats in the islands average more than 500 tons, well over the size legally required for boats undertaking international voyages to use Automatic Identification System (AIS) transceivers, which broadcast identifying information, headings, and other data about oceangoing vessels.

But fewer than 5 percent of them actually broadcast AIS signals at any given time.

This suggests a fleet intent on hiding its numbers and actions.

These large, modern vessels represent a stunning level of sunk capital costs but do not engage in much commercial activity.

Frequent satellite imagery shows that the vessels spend nearly all of their time anchored, often in large clusters.

This is true whether they are inside the lagoons at Subi and Mischief Reefs or loitering elsewhere in the Spratlys.

Operating in such close quarters is highly unusual and certainly not the way commercial fishing vessels usually operate.

Light falling net vessels, which account for the largest number of Chinese fishing boats in satellite imagery of the Spratlys, very rarely have their fishing gear deployed.

China’s trawlers, meanwhile, almost never actually trawl; instead, satellite imagery and the AIS signals of those few trawlers regularly broadcasting both show that they spend most of their time at anchor.

These unusual, and highly unprofitable, behaviors suggest that most of these supposed fishing boats are not making a living from fish.

When Chinese fishing vessels are not at Subi or Mischief Reefs, they are most often seen in satellite imagery anchored near Philippine- and Vietnamese-held outposts in the Spratlys.

This is corroborated by the small number of AIS signals detected from Chinese ships.

The most spectacular example of this behavior was the swarm of vessels from Subi Reef that dropped anchor between 2 and 5 nautical miles from Philippines-held Thitu Island as soon as Manila began modest upgrade work on that feature in December 2018.

The number of vessels seen in satellite imagery peaked at 95 on Dec. 20, 2018, before dropping to 42 by Jan. 26.

That presence continued into early June, when

reports suggested that China had begun to pull back the vessels.

The exact number of ships fluctuated from day to day, but almost none broadcast AIS or deployed fishing gear, and they operated in much closer quarters than any commercial fishing vessels would.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines confirmed that it had

monitored 275 individual Chinese vessels swarming near Thitu between January and March, and Manila filed protests with Beijing over their presence.

Meanwhile satellite imagery from March to April

showed another cluster of Chinese vessels displaying the same puzzling behavior around two other Philippine-held features: Loaita Cay and Loaita Island.

In that case, some dropped anchor just half a nautical mile from the isolated Philippine facility on Loaita Cay.

The only explanation that can make sense of all of these behaviors is that most of these vessels engage in the work of China’s maritime militia.

The job of that militia force has been well documented by sources as diverse as the U.S. Naval War College, reports from the Philippine military, and China’s own official documents outlining the militia’s role.

On a day-to-day basis it serves as a logistics and surveillance arm of the PLA, ferrying supplies to Chinese outposts, monitoring and reporting on the activities of other claimants, and engaging in joint training exercises with the military and law enforcement.

But they also move into more direct harassment of other nations’ vessels when called up—maneuvering dangerously close to foreign naval, law enforcement, and civilian vessels, sometimes shouldering and ramming them, and in general making it unsafe for other parties to operate in areas contested by Beijing, all while the PLA and China Coast Guard are kept in reserve as an implicit threat with a level of deniability.

Some analysts have offered alternative explanations for the curious, unproductive behavior of these ships.

But none of the theories stand up well to scrutiny.

One

suggestion is that these vessels never have gear in the water because they are actually reef fishers engaged in harvesting high-value species such as sea cucumbers and giant clams.

Relatedly, theorists posit that they don’t broadcast AIS because they are too small, or too old, or because they know that harvesting endangered species is illegal under Chinese law and they want to hide their activities.

Some have

even argued that the flood of vessels around Thitu was due to a surge in demand for seafood ahead of China’s Spring Festival.

But these explanations make little sense.

The sizes and types of vessels are easily determined from satellite imagery.

These fleets consist of large (over 160-foot) modern trawlers and falling net vessels, not the smaller (80- to 115-foot) motherships that accompany Chinese reef fishers around the Spratlys and other disputed features such as the Paracels and Scarborough Shoal, and certainly not the reef fishing boats themselves.

And while reef fishing vessels average just 15 feet, they can be seen in satellite imagery; it would be immediately obvious if hundreds were operating around Thitu Island.

There is plenty of sea cucumber harvesting in the Paracels—at Antelope Reef, for instance—and giant clam poaching has been

well documented across the South China Sea.

This is not that.

Another theory is that these vessels don’t appear to be fishing because they are involved in transshipment, serving in a support role by purchasing catch from and providing supplies to other fishing boats in the area.

That might fit if it was just some small percentage of the Chinese fleet involved.

But the opposite is true: Most Chinese ships observed in the Spratlys don’t appear to be commercially fishing.

They can’t all be support vessels; what would they be supporting?

A third hypothesis is that some of these vessels are simply

passing through the Spratlys to fraudulently collect the fuel subsidies China offers for ships that operate in the contested waters. After securing their subsidy, the theory goes, these boats likely head for more productive fishing grounds beyond the region.

This could be true for some small number of ships; it would be impossible to prove either way.

But this cannot explain the long-term presence of hundreds of vessels anchored around Thitu and other features.

And while only a small percentage of Chinese ships broadcast AIS in the Spratlys, those that do tend to spend months at a time there, mostly anchored.

The evidence that China is using hundreds of fishing vessels under the aegis of its publicly acknowledged maritime militia to assert claims and harass its neighbors in the Spratlys is considerable.

By contrast, the alternative theories are severely lacking.

No other convincing explanation has been offered for why so many fishing vessels are engaged for months at a time in activities that make little or no commercial sense, or why they are so intent on hiding their actions.

The maritime militia is the vanguard of China’s assertion of claims to the waters of the South China Sea.

It is the largest fleet operating in the area and is the most frequent aggressor toward both China’s neighbors and outside parties like the United States when asserting international rights in waters claimed by Beijing.

It operates as a nonuniformed, unprofessional force without proper training and outside of the frameworks of international maritime law, the military rules of engagement, or the multilateral mechanisms set up to prevent unsafe incidents at sea.

The next violent incident to take place in the South China Sea is far more likely to involve the Chinese militia than the PLA or China Coast Guard, and it will lack the mechanisms for communication and de-escalation that exist between those professional services and their counterparts in other nations.

The only way to avoid an eventual crisis triggered by these paramilitary vessels is to convince Beijing to take them off the board.

And the first step is to pull back the curtain of deniability, acknowledge that the evidence for their numbers and activities is overwhelming, and insist that the Chinese government be held accountable for their bad behavior.

Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said he expects ASEAN to further debate in the coming months the need for a 'Code of Conduct' with China over the South China Sea issue

Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah said he expects ASEAN to further debate in the coming months the need for a 'Code of Conduct' with China over the South China Sea issue

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.