Mountain Pass, California -- Less than an hour from the glitzy casinos and high-rise hotels of Las Vegas, the miners at Mountain Pass are reviving an industry that nearly disappeared from American soil.

This is the only mine in the country devoted to rare earths, elements essential to modern electronics. Rare earths are contained in everything from iPhones to wind turbines to Teslas.

"If there's going to be an American rare earths industry, it's gonna be led by us. We're it," said James Litinksy, the co-chairman of MP Materials, which owns the mine in Mountain Pass, California.

Shuttered after the previous owner went bankrupt in 2015, MP Materials has spent two years rebuilding the Mountain Pass operation.

"If there's going to be an American rare earths industry, it's gonna be led by us. We're it," said James Litinksy, the co-chairman of MP Materials, which owns the mine in Mountain Pass, California.

Shuttered after the previous owner went bankrupt in 2015, MP Materials has spent two years rebuilding the Mountain Pass operation.

Two hundred people now work at the mine site, carrying out blasts, trucking the minerals out of the mine and milling them into a powdered concentrate that is packed into dozens of white bags on site.

MP Materials say they supply about 10% of the world's rare earths, a set of 17 minerals with magnetic and conductive properties that help power most electronic devices.

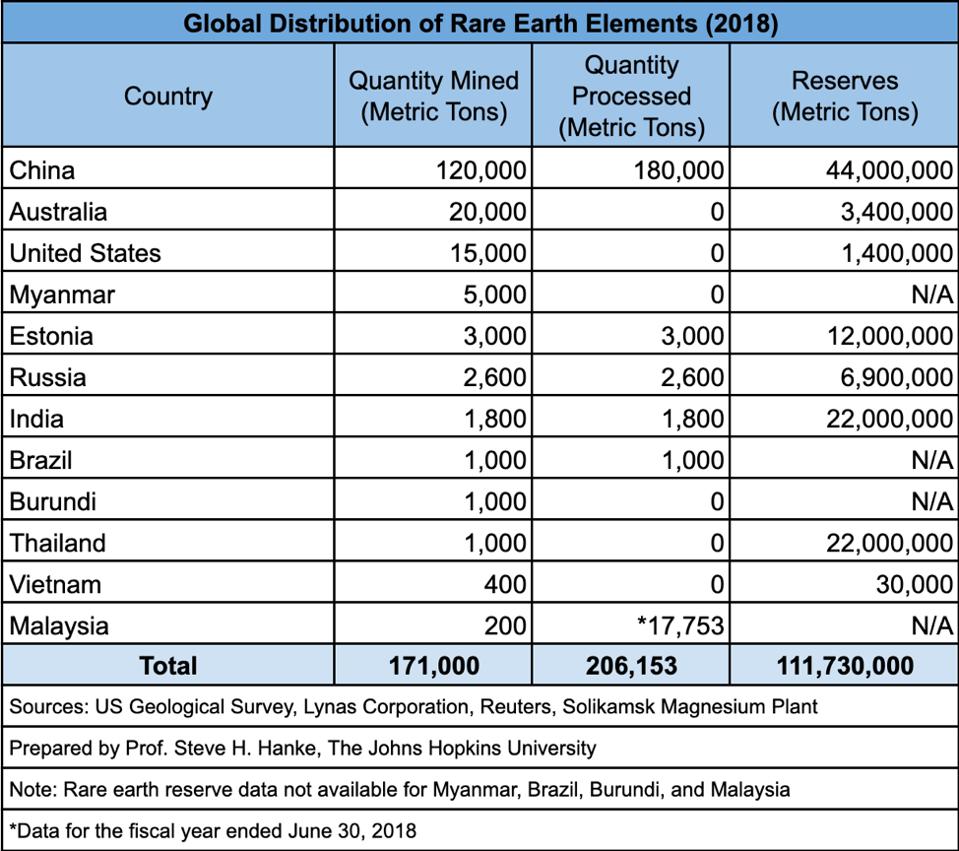

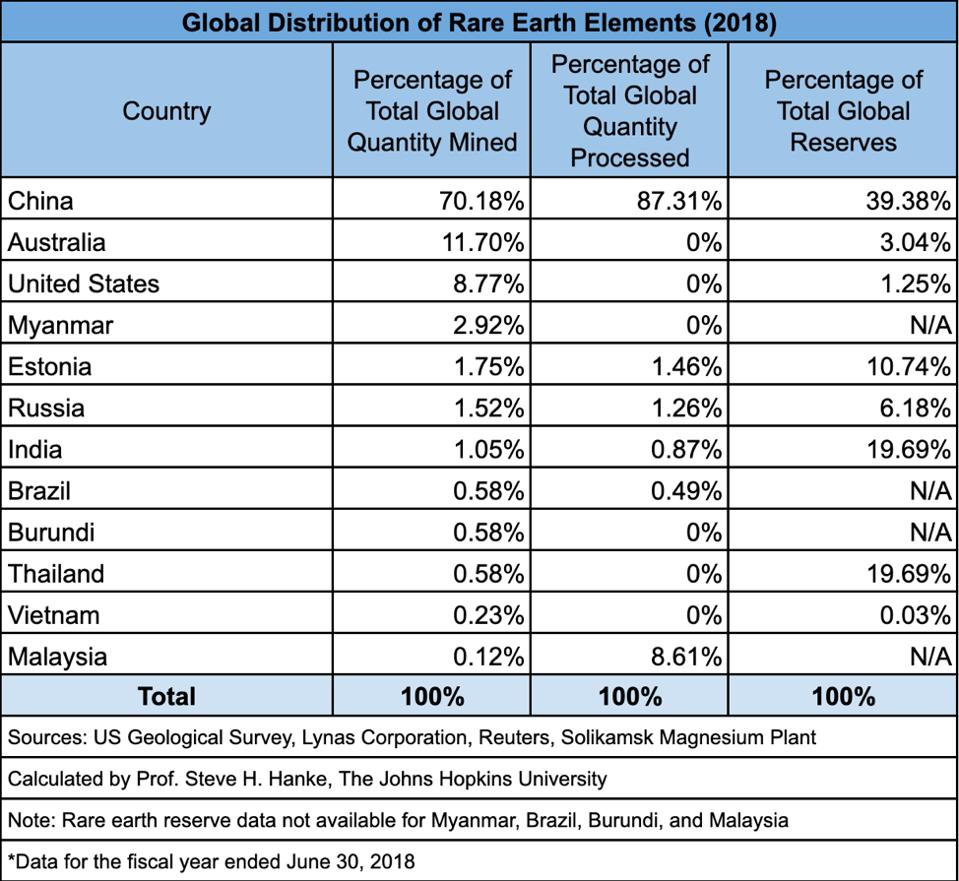

The rest of the rare earths industry is dominated by China, where labor costs are cheaper and environmental standards more lax.

The market for rare earths is expected to grow substantially over the next decade as the world becomes more and more dependent on high-tech products.

MP Materials say they supply about 10% of the world's rare earths, a set of 17 minerals with magnetic and conductive properties that help power most electronic devices.

The rest of the rare earths industry is dominated by China, where labor costs are cheaper and environmental standards more lax.

The market for rare earths is expected to grow substantially over the next decade as the world becomes more and more dependent on high-tech products.

With Washington and Beijing locked in a trade dispute, some in the US government and private industry want to see the United States develop an alternative supply of these essential elements -- first to increase mining of the minerals -- and eventually develop refining and production.

This Chinese dominance of such an important commodity has raised alarm bells in the Trump administration, particularly the defense department, which requires rare earths materials to build things like fighter jets, missile defense systems and satellites.

This Chinese dominance of such an important commodity has raised alarm bells in the Trump administration, particularly the defense department, which requires rare earths materials to build things like fighter jets, missile defense systems and satellites.

Chinese state media stoked such concerns in May, when it hinted the country could restrict access to rare earths as a weapon in the trade war.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping even paid a personal visit to one of the country's high-tech rare earths processors.

"The Chinese have wanted to cultivate that dependence and use it as a lever, and so I don't think it's any surprise that they are considering using it more dramatically," said Eugene Gholz, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame and former Pentagon senior adviser.

The Defense Department says its working with President Donald Trump, Congress and industry to try and mitigate US reliance on China for rare earth minerals.

The pit at the MP Materials' Mountain Pass mine in California. It's the only operating mine in the United States that provides rare earths, ingredients that are key for producing high-tech products like cell phones and electric vehicles.

"The Chinese have wanted to cultivate that dependence and use it as a lever, and so I don't think it's any surprise that they are considering using it more dramatically," said Eugene Gholz, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame and former Pentagon senior adviser.

The Defense Department says its working with President Donald Trump, Congress and industry to try and mitigate US reliance on China for rare earth minerals.

The pit at the MP Materials' Mountain Pass mine in California. It's the only operating mine in the United States that provides rare earths, ingredients that are key for producing high-tech products like cell phones and electric vehicles.

It's easy to see how Mountain Pass could be central to this effort.

Experts say the site contains one of the world's highest quality deposits of this type of material, with a high proportion of naturally occurring rare earths and little of the radioactive elements that can make this type of mining dangerous or environmentally damaging.

The mine started operations in the 1950s by producing europium, which was used to make red colors in early televisions.

The trouble is that Mountain Pass currently has no ability to separate the rare earths into the type of products required for technological supply chains.

The trouble is that Mountain Pass currently has no ability to separate the rare earths into the type of products required for technological supply chains.

All of its final product is exported back to China for processing.

Building capacity

Experts say this step is the true impediment to diversifying the supply chain.

Building capacity

Experts say this step is the true impediment to diversifying the supply chain.

"Mining and concentration is actually one of the easier steps," said Roderick Eggert, an economics professor at Colorado School of Mines.

"The real challenge is actually downstream in separations."

A US defense official told CNN Business that the Pentagon expects to soon receive additional authorities and resources from the Trump White House to begin developing non-China rare earth refinery options, with a focus on building up capacity within allied countries.

James Litinsky believes Mountain Pass is up for the challenge.

A US defense official told CNN Business that the Pentagon expects to soon receive additional authorities and resources from the Trump White House to begin developing non-China rare earth refinery options, with a focus on building up capacity within allied countries.

James Litinsky believes Mountain Pass is up for the challenge.

He says the site will have its own separations facility operating by next year, allowing them to make rare earth oxides they can sell directly to global companies.

They are taking advantage of $1.7 billion the previous owner spent to upgrade the site and make it environmentally friendly before abandoning it in the bankruptcy, including building a massive separations facility that currently sits unused.

A minority non-voting stake in MP Materials is owned by a Chinese company that is listed on the stock exchange in Shanghai.

Someday, Litinsky hopes his company may be able to carry out the entire supply chain, from mining all the way into production of miniaturized magnets, motors and other rare earth products that go directly into consumer goods.

Someday, Litinsky hopes his company may be able to carry out the entire supply chain, from mining all the way into production of miniaturized magnets, motors and other rare earth products that go directly into consumer goods.

Right now, nearly all of that final step is done in China or Japan.

He said the trade war between Washington and Beijing provided an additional impetus for the company to achieve its goal of creating "a real Western allied super major" -- an alternative supply chain to the current one monopolized by China.

A worker checks on operations at the processing facility at the Mountain Pass rare earths mine in California.

He said the trade war between Washington and Beijing provided an additional impetus for the company to achieve its goal of creating "a real Western allied super major" -- an alternative supply chain to the current one monopolized by China.

A worker checks on operations at the processing facility at the Mountain Pass rare earths mine in California.

"There were a lot of people who doubted we could make this work and so we felt an extra burden and a duty," he said.

"But I've said there has definitely been a heightened sense of awareness of what we are up to since the trade war started."

Litinsky won't discuss his specific contacts with the government but said some officials have visited the Mountain Pass site.

Litinsky won't discuss his specific contacts with the government but said some officials have visited the Mountain Pass site.

Trade war or no trade war, he believes he's building a business that's economically viable and can compete in an open market.

He hopes officials and corporations see the company's strategic importance and recognize the advantage Chinese producers have because of state subsidies and looser environmental regulations.

"We don't want a handout," Litinsky said.

"We don't want a handout," Litinsky said.

"We don't need that help. We just need a level playing field to compete."

The demand for rare earths is expected to grow alongside the market for high-tech products.

The demand for rare earths is expected to grow alongside the market for high-tech products.

Research firm Adams Intelligence estimates that between 2018 and 2030 the value of demand will quadruple, turning rare earths into at nearly $16 billion market.

Both Gholz and Eggert believe this growing demand and rising prices, combined with market pressure for a more diverse, sustainable supply chain, may bring the Chinese control of rare earths to an end, even without government intervention.

That shift seems to be what Mountain Pass is betting on.

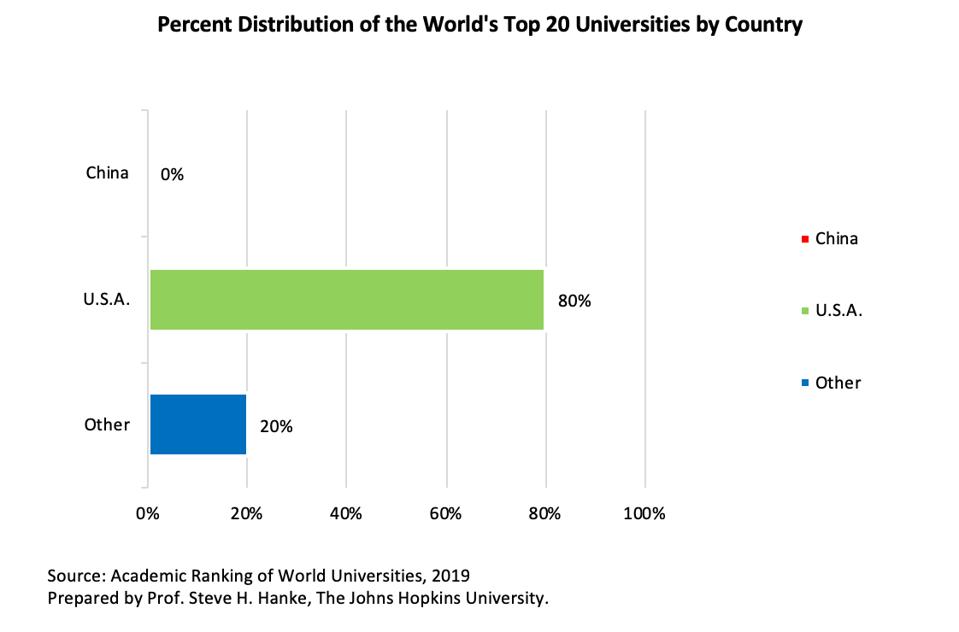

"As a matter of national security we need to lead in these industries of tomorrow and I think that that's probably where the military is most focused," he said.

Both Gholz and Eggert believe this growing demand and rising prices, combined with market pressure for a more diverse, sustainable supply chain, may bring the Chinese control of rare earths to an end, even without government intervention.

That shift seems to be what Mountain Pass is betting on.

"As a matter of national security we need to lead in these industries of tomorrow and I think that that's probably where the military is most focused," he said.

"They actually ultimately make up a much smaller percentage of the market than electric vehicles, wind turbines all these significant industries of tomorrow that will lead to millions of jobs. That will be the arena with which this situation plays out. "