BY MUHAMMAD AKBAR NOTEZAI

Pakistani naval personnel stand guard near a ship at the Gwadar port on Nov. 13, 2016.

In 2015, when Chinese dictator Xi Jinping’s plane entered Pakistani airspace, eight Pakistan Air Force jets scrambled to escort it.

The country’s leadership warmly welcomed the Chinese leader—and his money.

On his two-day state visit, he announced a multibillion-dollar project called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which would form part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and would revolve around the development of a huge port in the city of Gwadar.

Gwadar, a formerly isolated city in Pakistan’s southwestern Balochistan province, boomed.

Gwadar, a formerly isolated city in Pakistan’s southwestern Balochistan province, boomed.

As soon as the CPEC was announced, tourists, including journalists, started visiting Gwadar.

The Pearl Continental, the only five-star hotel in the area, had been on the brink of closure.

Now guests thronged.

But not everyone was happy about that.

Baloch nationalists and underground organizations opposed the CPEC from the beginning, on the grounds that it would turn the Baloch people into a minority in their own province.

They threatened attacks on any CPEC project anywhere in Balochistan.

There was plenty of reason to believe their threats.

There was plenty of reason to believe their threats.

During the tenure of Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf, who led Pakistan from 1999 to 2008, Baloch insurgents killed Chinese engineers and workers in the province.

One of the incidents took place in Gwadar, where in May 2004, militants killed three Chinese engineers.

The engineers had been driving to work.

When they slowed down to pass over a speed bump, a terrorist in a nearby car detonated the barrier with a remote control.

In recent years, violence had waned.

In recent years, violence had waned.

There were no new projects, and the city seemed to have settled into its own rhythm.

But following the CPEC announcement, according to the News International, a Pakistani English daily, Pakistan deployed a total of 17,177 security personnel from the Army and other security forces to ensure the security of Chinese nationals.

In the years since, Gwadar has become something of a military cantonment.

Army, police, and other law enforcers mill about.

And locals traveling around Gwadar face routine harassment at security checkpoints.

The policing has done little to deter attacks.

And locals traveling around Gwadar face routine harassment at security checkpoints.

The policing has done little to deter attacks.

In recent months, two reported incidents have put the province on edge.

The first attack occurred on April 18, when 15 to 20 Baloch insurgents dressed in military uniforms forms forced 14 passengers off a public bus and shot them, one by one.

Most of victims were from the Pakistan Navy and Coast Guards, whom Baloch insurgents view as an occupying force.

Then, on May 11, the Pearl Continental in the heart of Gwadar came under fire.

Then, on May 11, the Pearl Continental in the heart of Gwadar came under fire.

Situated on a promontory overlooking the port and the Arabian Sea, the hotel is mammoth and a favorite of foreign dignitaries.

Security there is intense, and since it is near Gwadar’s port area there are already plenty of military personnel in the area.

Three armed attackers from the Balochistan Liberation Army’s Majeed Brigade nevertheless managed to breach the defenses and open fire on people inside.

According to officials, five individuals—four hotel employees, including three security guards, and a navy officer—lost their lives.

The Pearl Continental attack in particular bodes ill for Chinese investment in Balochistan.

Before this month, it was hard to imagine that Baloch insurgents would be capable of carrying out the attack in the center of Gwadar, even with the local support.

The Pearl Continental attack in particular bodes ill for Chinese investment in Balochistan.

Before this month, it was hard to imagine that Baloch insurgents would be capable of carrying out the attack in the center of Gwadar, even with the local support.

But now any sense of security has been undermined.

Established in 2011, the Majeed Brigade, a suicide attack squad within the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), is reportedly named after Abdul Majeed Baloch, who attempted to assassinate then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1974 in Balochistan.

Established in 2011, the Majeed Brigade, a suicide attack squad within the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), is reportedly named after Abdul Majeed Baloch, who attempted to assassinate then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1974 in Balochistan.

In 1973, Bhutto had ordered a military operation against the Baloch because Baloch insurgents had vowed war against the state of Pakistan after Islamabad had dismissed the democratically elected National Awami Party government in Balochistan in February 1973.

The operation triggered a major insurgency in Balochistan that lasted until 1977.

Majeed was killed by security forces before he could carry out his plan against Bhutto.

In the first several years after the BLA was formed in 2000, it mostly waged attacks on national security forces, state infrastructure, and Punjabi settlers.

In the first several years after the BLA was formed in 2000, it mostly waged attacks on national security forces, state infrastructure, and Punjabi settlers.

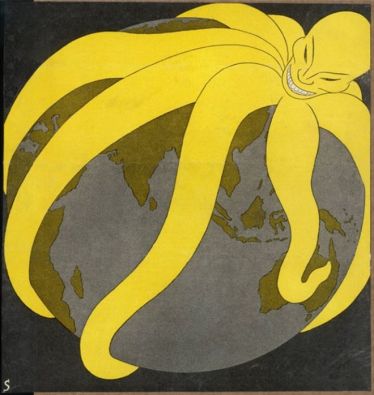

In more recent years, under Aslam Baloch, who died in Kandahar in December 2018, the Majeed Brigade has focused on Chinese nationals and Chinese-funded projects.

Such attacks seemed more likely to provoke media attention.

He tapped his oldest son, Rehan Baloch, for a suicide attack on Chinese engineers in Dalbandin, a city in Balochistan, last August.

The attack resulted in minor injuries for the engineers.

He also oversaw an attack on the Chinese consulate in Karachi a few months later.

Two police officials and two visa applicants were killed.

As these incidents suggest, the Majeed Brigade is gaining momentum.

As these incidents suggest, the Majeed Brigade is gaining momentum.

And it is joined by new groups, such as the Baloch Raaji Aajoi Sangar, an alliance of Baloch separatist groups specifically focused on attacking CPEC projects.

From the beginning, the Baloch have been pushed to the wall.

They have never been treated as equal citizens of Pakistan, nor have they been given equal constitutional, economic, and political opportunities.

This is why some Baloch protest peacefully, some do nothing, and some have taken up arms against the state.