Beijing’s island-grabbing campaign is getting close to home. It’s muscling in on tiny nations from the Indian to the Pacific Oceans.By Jamie Seidel

CHINA’s island-grabbing campaign is getting close to home.

It’s muscling in on tiny nations from the Indian to the Pacific Oceans.

But Australia’s begun pushing back.

Ceylon. Savo Island. Coral Sea. Guadalcanal. Gilbert and Marshall Islands. Tarawa. Truk. Guam.

These were names plucked from obscurity by bloody battles against Japan during World War II.

They were battles fought because these seemingly insignificant islands — some little more than coral atolls and volcanic outcrops — are important.

They are remote outposts, rare landfalls in vast oceans.

They sit astride shipping lanes that carry the lifeblood of South-East Asia’s and Oceania’s economies.

Those controlling these specks on the map potentially have an impact on world affairs seemingly out of all proportion.

Not since the darkest days of World War II has Australia begun to feel the pressure of isolation and constraint.

Germany did little more than harass our shipping in the Indian Ocean, carrying troops and equipment to the Middle East and vital resources in return.

But Japan’s overwhelming raids on Darwin and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1942 brutally demonstrated just how vulnerable we were.

And

once the Pacific Islands began to fall, the links between Australia and the United States began to look tenuous as well. A snapshot of shipping flowing to and from Australia, and through the region, from www.shipmap.org.

A snapshot of shipping flowing to and from Australia, and through the region, from www.shipmap.org.That encirclement of Australia was with steel ships, aluminium aircraft and the blood and sweat of tens of thousands of troops.

It’s an encirclement some analysts fear we are experiencing again.

But in place of warships and tanks,

China is steamrolling across our region with promises of grand works of infrastructure — and weaponised loans.Debt-trap diplomacy is behind a new land grab.

It’s the lure of loans pushed on poor countries that cannot afford to repay them.

Now new regional names are registering on Australia’s radar as they teeter and fall.

Male. Manus. Luganville. Wewak.

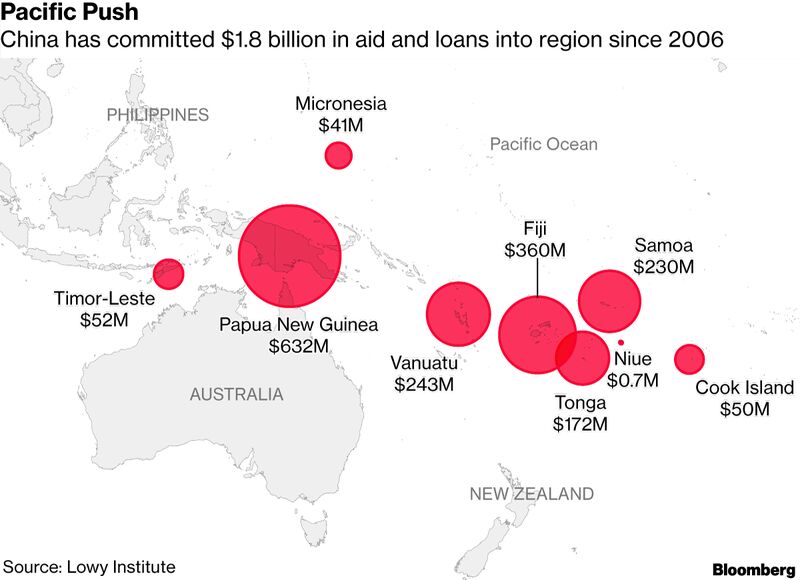

China has showered small nations such as Vanuatu, Tonga and the Solomon Islands with concessional loans.

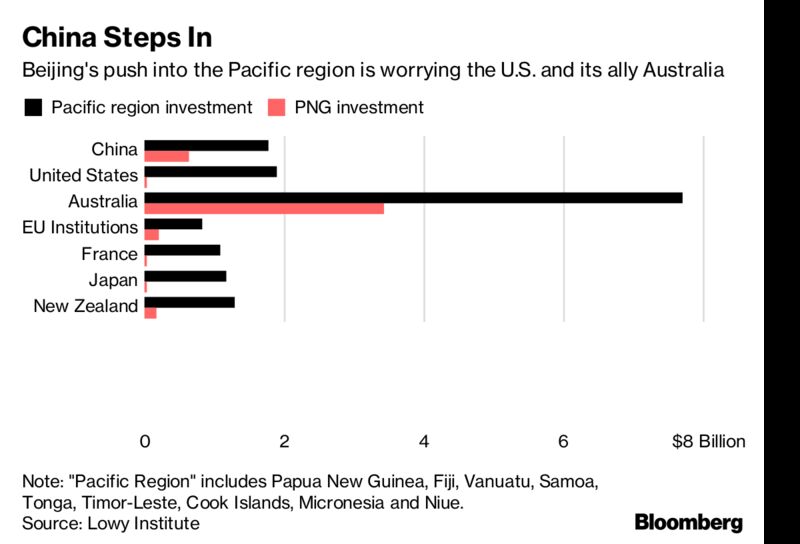

The Lowy Institute think-tank estimates

Beijing pushed more than $2.3 billion into to the region between 2006 and 2016.

The fates of these far-flung places could be a bellwether of our own. The new runway of Velana International Airport in Male, Maldives.

The new runway of Velana International Airport in Male, Maldives.

ISLANDS IN CHAINSLast week, the scattering of tiny islands that is the Maldives Archipelago in the Indian Ocean

opened an enormous new runway.

Velana International Airport is on the island of Male.

The broad new airstrip was built on land reclaimed from the sea by a Chinese state-backed company, using money from … Beijing.

It followed close on the heels of another controversial Maldives-China project.

“The nation celebrated the opening of the China-Maldives Friendship Bridge, hailed as the project of the century in the small Indian Ocean nation and a hallmark project of the China-proposed Belt and Road initiative (BRI),”

the state-run Global Times reported in August.

“Although some said the Maldivian government will bear a heavy debt from the massive infrastructure co-operation with China, Maldivian officials said they appreciate China’s generosity.”

It was a pointed — if unconvincing — rebuttal of the ‘debt-trap’ narrative.

But

Beijing is already in a position in the tiny strife-torn nation to seize both as collateral — and turn them towards military purposes.Then there’s Manus.

The military base established on Manus Island during World War II has suddenly become of interest to both Beijing and Canberra.

The military base established on Manus Island during World War II has suddenly become of interest to both Beijing and Canberra. Once part of the British Admiralty Islands, it was seized from the Japanese by the United States for use as a major World War II naval staging post.

Now part of

Papua New Guinea, it has once again returned to the world’s stage.

China has been showing interest.

Having airfield and port facilities there could boost its ‘Island Chain’ ambitions, and establish a prickly thorn between Australia and US facilities on the island of Guam.But Australia has begun pushing back.

“The Pacific is a very high-priority area of strategic national security interest for Australia,” Prime Minister

Scott Morrison said, refusing to confirm or deny reports Australian defence officials had visited the Lombrum Naval Base on Manus to assess its potential for expansion.

Details of any future jointly-operated, upgraded facility there will not be revealed before the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Port Moresby in November.

The Maldives and Manus are just the most recent in a rapid-pace series of international power plays in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Relations between Canberra and Beijing plunged to a new low earlier this year after we criticised China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ and undue influence in the politics of countries throughout the region — including our own.

Beijing lashed back, using its state-run media to label Australia as an “arrogant overlord”.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping looks on during bilateral talks at the Maldives President’s Office in the capital island Male, where he sought backing for a “21st century maritime silk road”. WAKING DRAGON

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping looks on during bilateral talks at the Maldives President’s Office in the capital island Male, where he sought backing for a “21st century maritime silk road”. WAKING DRAGONIt’s about

Xi Jinping’s grand vision.

He sees China’s influence extending far beyond its own borders.

In 2013, he detailed his grand scheme to revitalise the ancient Silk Road and sea spice routes.

It would ‘restore’ China’s position at the centre of a trade hub extending to Europe and Africa.

The Belt and Road Initiative — as it has become known — demands a networks of ports, airfields, roads and railways spanning the globe.

Chinese state-owned companies now control about 76 ports in 35 countries — including Darwin.

And while Beijing openly insists it only wants to use these ports for commercial purposes, its warships and submarines have already been seen docked in several.

Now Xi wants another ‘Silk Road’ — this time extending into the Pacific.

Ministers from Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu and Fiji were among those invited to Beijing in 2017 for the launch of the Belt and Road project.

They were offered access to $55 billion in loans.

This sparked alarm in Australia, the US and Europe.

Beijing’s loans do not come cheap.“Such indebtedness gives China significant leverage over Pacific Island countries and may see China place pressure on Pacific nations to

convert loans into equity in infrastructure,”

the Lowy Institute’s recent Safeguarding Australia’s Security Interests report warns.

“It’s not ‘win-win’ for China and the recipient, but simply ‘win’ for China, which not only gets access to local resources and new markets, and forward presence, but can coerce the recipient state to pay a ‘tribute’ to Beijing by ceding local assets when it can’t pay back its debts,” the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Dr Malcolm Davis notes.

Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka is an example of Beijing’s debt-trap diplomacy. China has won a 99-year-lease on the facility, and a 70pc controlling stake in its management.

Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka is an example of Beijing’s debt-trap diplomacy. China has won a 99-year-lease on the facility, and a 70pc controlling stake in its management.An editorial published by the state-run

Global Times says South Pacific nations had been ‘bewitched’ by Western countries including Australia and the US “who sought to gain political leverage in the region”.

“Unlike Western aid, which always comes with political and economic conditions, Chinese aid has been widely welcomed by South Pacific nations as it has no political conditions,” it quoted research fellow in Australian Studies Yu Lei as saying.

But China does not openly declare its international aid projects in the same way other nations such as Australia does.

This has raised a degree of anxiety about exactly how much it is spending, where — and why.Now, China’s taking a leaf out of the US playbook.

It wants strong military facilities spaced around its ‘sphere of influence’.

It calls that sphere the Second Island Chain — a rough line from Japan in the north to Papua New Guinea in the south.

But as Beijing’s dominance over the First Island Chain (including Taiwan, the Spratlys, and Paracels) of the South China Sea seems all but complete, a ‘Third Island Chain’ appears to be emerging — extending from the Maldives in the west to Fiji in the east.

“The most troubling implication for Australian interests is that a future naval or air base in Vanuatu would give China a foothold for operations to coerce Australia, outflank the US and its base on US territory at Guam, and collect intelligence in a regional security crisis,” Rory Medcalf, the head of the National Security College at the Australian National University,

wrote in a recent Lowy Institute report.

It’s a similar story for the Maldives, potentially cutting Australia’s fuel supplies and trade links to Singapore, India and Europe.

United States, Indian and Japanese warships exercise together. Concern at Beijing’s expansive ambitions have drawn regional powers together. GAME OF THRONES

United States, Indian and Japanese warships exercise together. Concern at Beijing’s expansive ambitions have drawn regional powers together. GAME OF THRONESChina’s rapid expansion has not gone unnoticed.

In a speech to Australia’s Parliament in 2011, then US President

Barack Obama announced a ‘pivot’ back to the Asia-Pacific.

Existing military facilities would be reinforced and strengthened.

Forces would be based in Darwin.

It wasn’t all about troops.

Fresh efforts would be made on the diplomatic and economic fronts.

Chief among these was the proposed (now abandoned) Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

“This allowed Washington to counter Beijing’s concerns that the pivot was primarily a military move aimed at containing a rising China,” the Lowy Institute says.

“However, the decision by the Trump administration to abandon the TPP has given US strategy in the Indo-Pacific more of a military character.”

President Trump’s attitude towards international agreements and treaties has unsettled South-East Asia.

Will he be true to his nation’s word?

Or would he pull the US out?

It’s a question that has prompted the region to look to strengthen its own relationships.

Generally, the Melanesian states have been seen as Australia’s area of responsibility while the US and New Zealand watch over the Polynesian islands.

In recent decades, that influence has weakened.

“Being the dominant traditional power has not always made Canberra popular in Pacific Island nations, despite being the region’s largest provider of aid,” the Lowy Institute notes.

“However, failing to forge stronger regional partnerships now, in the hope that the current geostrategic dynamics will not change, contains significant risk.”

Things haven’t been getting better.

Australia has been ‘showing the flag’ in the Indo-Pacific, sending its new helicopter carrying assault ships on visits as a demonstration of its military — and disaster relief — capacity.

Australia has been ‘showing the flag’ in the Indo-Pacific, sending its new helicopter carrying assault ships on visits as a demonstration of its military — and disaster relief — capacity. The Pacific Islands have repeatedly expressed dismay at the deep state of denial Australian and US politicians are in over the looming global warming crisis.

After all, their low-lying islands are already falling victim to rising sea levels.

President Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement earlier this year was called “pretty selfish” by the former president of Kiribati.

The Prime Minister of Tuvalu went further: “I think this is a very destructive, obstructive statement from a leader of perhaps the biggest polluter on earth and we are very disappointed as a small island country already suffering the effects of climate change.”

China, at least, pays lip-service to the international threat.

So, with this issue at least, it has stolen the moral upper ground.

And then there are the promises of Xi Jinping.

He’s been touting his ‘Chinese model’ as a “new option for other countries who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.”

But his real purpose,

says Dr Davis, is more ominous.

“Chinese ambitions don’t end at the reunification of Taiwan and China on Beijing’s terms or control of the South China Sea. China is clearly emerging as a hegemonic power, exploiting both soft-power inducements and hard-power threats to reassert itself as a new Middle Kingdom, and overturning what it sees to be a century of humiliation.

Part of the ‘China Dream’ is ensuring that its periphery is secure through a belt of vassal states that accede to Beijing’s interests.”

A Chinese H6K takes off into a golden dawn. Beijing has been proudly boasting of its position as a new world power. DRAGONS AT THE GATES

A Chinese H6K takes off into a golden dawn. Beijing has been proudly boasting of its position as a new world power. DRAGONS AT THE GATESThe US Pentagon is alert — and alarmed.

“China is using its economic penalties, influence operations, and implied military threats to persuade other states to heed its political and security agenda,” the US National Security Strategy of December 2017 reads.

“Chinese dominance risks diminishing the sovereignty of many states in the Indo-Pacific region”.

That includes Australia.

Beijing has been doing all it can to expand its status as a maritime power.

It now has 43 attack submarines at its disposal — that’s more than the United States.

It’s also been launching surface ships at an unprecedented rate, some 24 new destroyers and 31 new frigates since 2000 alone.

While formidable, it’s not likely to rival the US for another 20 years.

But it will be powerful enough to project significant power wherever it desires.

“China’s confidence on the international stage has been bolstered by its perceived successes in the South China Sea where it has occupied, and physically enhanced, a series of uninhabited reefs,” the Lowy Institute report warns.

Now China is pursuing a military and diplomatic strategy which “seeks Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near-term and displacement of the United States to achieve global pre-eminence in the future”,

the US National Defense Strategy of 2018 states.

China’s actions are “undermining the international order from within the system by exploiting its benefits while simultaneously undercutting its principles.” F-35B Lightning IIs with US Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 211 fly over Wake Island, one of a series of military bases retained after World War II. China wants its own ‘buffer zone’ of islands in the Pacific and Indian Ocean to protect its interests.

F-35B Lightning IIs with US Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 211 fly over Wake Island, one of a series of military bases retained after World War II. China wants its own ‘buffer zone’ of islands in the Pacific and Indian Ocean to protect its interests. And that brings it head-to-head with the US along the ‘Second Island Chain’.

At its heart is the island of Guam.

It is a US territory and major defence facility.

The free compact states of Palau, the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia all operate under a post-war agreement with the US, allowing a base on the Marshall Islands and the veto over any military access by any other nation.

From the outset, this was intended to provide the US with a Pacific ‘buffer zone’ between itself and Asia.

Now China wants a ‘buffer zone’ between itself and the US.

At the bottom of the ‘Second Island Chain’ is Papua New Guinea, and the island of Manus.

Australia’s moves to thwart Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road’ projects are a sign of growing ‘push-back’ from the West.But Beijing is determined — and persistent.

“Powerful drivers are converging in a way that is reshaping the international order and challenging Australia’s interests. The United States has been the dominant power in our region throughout Australia’s post-second world history. China is challenging America’s position,”

Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper reads.

The Royal Australian Navy Anzac Class Frigate

The Royal Australian Navy Anzac Class Frigate HMAS Stuart

is observed through periscope on board the RAN Collins

Class Submarine HMAS Sheean.

While isolated, Australia is highly dependent on its shipping lanes to the northeast and northwest.

LOOK TO YOUR MOAT

The 2016 Defence White Paper made the situation pretty clear: “Australia cannot be secure if our immediate neighbourhood including Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste and Pacific Island Countries becomes a source of threat to Australia. This includes the threat of a foreign military power seeking influence in ways that could challenge the security of our maritime approaches or transnational crime targeting Australian interests …”

Three of Australia’s five main maritime trade routes pass through the Pacific.

The two largest are in the Indian Ocean.

Our trade with the US passes near New Caledonia and Fiji.

Those to and from Japan, Taiwan — and China — largely go past New Britain and Papua New Guinea, or through the Solomon Islands, Bougainville and New Britain.

In the west, our trade funnels past Sri Lanka, the Maldives and Indonesia.

If there is trouble in the Pacific, trade will have to divert through the Torres Strait to Indonesia’s Suda and Lombok Straits.

If there is trouble in the Indian Ocean, exports from Western Australia — such as gas and iron ore — would have to take a long detour through the Tasman Sea.

HMAS Adelaide

berthed at the Port of Suva in June. “Australia’s reliance on maritime trade with and through South East Asia, including energy supplies, means the security of our maritime approaches and trade routes within South East Asia must be protected, as must freedom of navigation, which provides for the free flow of maritime trade in international waters,” the

Defence White Paper notes.

“The Government will work with Pacific Island Countries to strengthen their ability to manage internal, transnational and border security challenges …

This includes working to limit the influence of any actor from outside the region with interests inimical to our own.”

Australia is gifting 19 new patrol boats to 12 Pacific Island Nations.

The project, which includes maintenance and support and costs $2 billion over 30 years, has seen the first boats delivered this year.

They are part of a co-ordinated project including RAAF surveillance and visits by RAN warships.

The Solomon Islands has recently signed a security treaty with Australia.

Security partnership understandings have been negotiated with Tuvalu and Nauru.

Kiribati is in talks.

Australia has also been showing the flag.

One of our new helicopter-carrying assault ships,

HMS Adelaide, joined three other warships on a 13 week Indo-Pacific Endeavour exercise.

Just in case our Pacific partners had forgotten.

Restoring Australia’s place in its region will take considerably more effort, the Lowy Institute warns. We must offer government services, access to labour markets, and assist with defence “in return for an undertaking that foreign military forces or installations would not be allowed in these countries. This would mitigate the risk of China gaining access to dual-use facilities in these nations in return for debt reduction, while safeguarding the sovereignty of these independent nations.”

A Chinese H6K strategic bomber flies over disputed coral reefs in the South China Sea. Beijing is looking for similar island bases in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

A Chinese H6K strategic bomber flies over disputed coral reefs in the South China Sea. Beijing is looking for similar island bases in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

ISLAND CHESSBOARD

PACIFIC OCEANWhile not having ‘traditional’ trade links to justify its interest in the region, China has aggressively stepped forward with the promise of cheap loans into a region somewhat disillusioned by Australia and the US.

- FIJI: After a 2006 military coup, Australia — among others — imposed sanctions on Fiji until it returned to democratic rule. China places no value in such systems of government. So it stepped in, offering loans for infrastructure projects built by Chinese labourers. While not entirely welcomed by the populace, it gave Beijing powerful influence among Fiji’s leaders.

- PAPUA NEW GUINEA: Its military officers have also been invited to China to attend training courses.

- SAMOA: Beijing is increasingly pressuring this island nation to repay its debts. Like many others.

- SOLOMON ISLANDS: Earlier this year, Prime Minister Turnbull promised the Solomons (and Papua New Guinea) that Australia would pay for a new undersea internet cable in order to brush aside the state-controlled Chinese telco giant Huawei, as well as relieve the island nations of the financial burden.

- TONGA: In 2013, 64 per cent of Tonga’s foreign debt was owed to China. That amounted to 43 per cent of its annual GDP. Previously, Tonga has said it may have to seek a write-off of this burden by allowing Beijing to establish a naval base on the island.

- VANUATU: Vanuatu owes Beijing some $US1.7 billion. Earlier this year, reports that China was seeking a ‘permanent military presence’ on the island sparked dismay in Australia. Both Vanuatu and China denied any such proposal had been made. But Prime Minister Turnbull sounded unconvinced: “We would view with great concern the establishment of any foreign military bases in those Pacific island countries and neighbours of ours,” he said. The country’s newly built $85 million Luganville wharf, which was funded by China and seems more suited to navy vessels than cruise ships.

INDIAN OCEANBeijing is already well advanced in its moves to establish a network of naval and air bases in the Indian Ocean.

The number of ships and submarines it has stationed there has been steadily growing.

But China needs more.

Chief on its shopping list are major airfields capable of supporting its long-range reconnaissance aircraft and bombers.

It also needs submarine support facilities and logistics infrastructure extending from the northeastern Indian Ocean to the west.

- DJIBOUTI: In 2017, Beijing opened its first overseas military facility. This is in Djibouti on the shores of the troubled Red Sea. It’s already been openly tussling with a neighbouring US facility, allegedly blinding its pilots with lasers.

- MALDIVES: This archipelago in the central Indian Ocean underwent a coup earlier this year, installing Abdulla Yameen -- who has been implicated in several corruption scandals and is seen as a close friend of Beijing -- as president. But elections this week has seen him deposed. How the Maldives will pay for a major Chinese-funded and built airstrip, and an equally ambitious bridge project, is yet to be seen. And there’s an abandoned British naval facility ripe for the pickings on the island of Gan.

- MYANMAR: A naval base on the Indian Ocean side of the chokepoint Malacca Strait would give China the ability to project power across the region and the Bay of Bengal. Beijing has built a new port at Kyaukpyu — and taken a 70 per cent controlling stake in it after Myanmar defaulted on repayments.

- PAKISTAN: China is in advanced talks with Pakistan to build a base on the Arabian Sea, near the city of Gwadar.

- SRI LANKA: An inability to repay $6 billion in debt to China has already given Beijing a windfall in Sri Lanka. A controlling 70 per cent stake, along with a 99-year-lease, in the port of Hambantota has been given to a state-run Chinese company in an effort to pay-down the burden. This port sits close to the major Indian Ocean sea lanes.

- THAILAND: China is pushing Thailand for the construction of a 100km canal on the scale of Panama, linking the South China Sea with the Bay of Bengal and bypassing the crowded Strait of Malacca. India fears the economically unviable Kra Canal will quickly fall under the control of Beijing, dramatically improving its ability to influence the balance of power in the Indian Ocean. Thailand, under pressure from all sides, is yet to accept — or reject — the project.

Sri Lankan monks take pictures at the opening of an airport built with Chinese money in Hambantota.

Sri Lankan monks take pictures at the opening of an airport built with Chinese money in Hambantota.