Hong Kong -- Arslan Hidayat was at work when the Chinese attacked.

"My phone was going 'bring, bring, bring,'" said the 31-year-old English teacher.

"I was like, What the hell's going on?"

A Facebook page he helps run which focuses on the Uyghur ethnic minority was being flooded by thousands of comments in a targeted attack by the Chinese.

Australian-born Hidayat lives with his wife and children in Istanbul, Turkey, which is home to a large Uyghur diaspora.

A Facebook page he helps run which focuses on the Uyghur ethnic minority was being flooded by thousands of comments in a targeted attack by the Chinese.

Australian-born Hidayat lives with his wife and children in Istanbul, Turkey, which is home to a large Uyghur diaspora.

Their relatives in China have been swept up by the Communist Party's crackdown on the largely Muslim minority group in the country's far-western colony of East Turkestan.

Hidayat has just such a story.

Hidayat has just such a story.

He has not heard from his father-in-law, Adil Mijit, a popular comedian and entertainer, for over five months.

The family fears he is among the more than one million Uyghurs detained in a vast system of concentration camps established in East Turkestan.

China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions about Adil Mijit's whereabouts.

Hidayat has publicized this story, and many others like it, on a Facebook page, Talk to East Turkestan (TET), to thousands of followers.

China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions about Adil Mijit's whereabouts.

Hidayat has publicized this story, and many others like it, on a Facebook page, Talk to East Turkestan (TET), to thousands of followers.

Facebook is banned in China, as are Twitter and Reddit — accessing them requires jumping the Great Firewall, the country's vast censorship and surveillance apparatus.

Despite this, these sites appear to be becoming a key battleground of Chinese influence, as a growing army of Chinese assemble on forums and in Facebook groups to attack voices hostile to Beijing's interests.

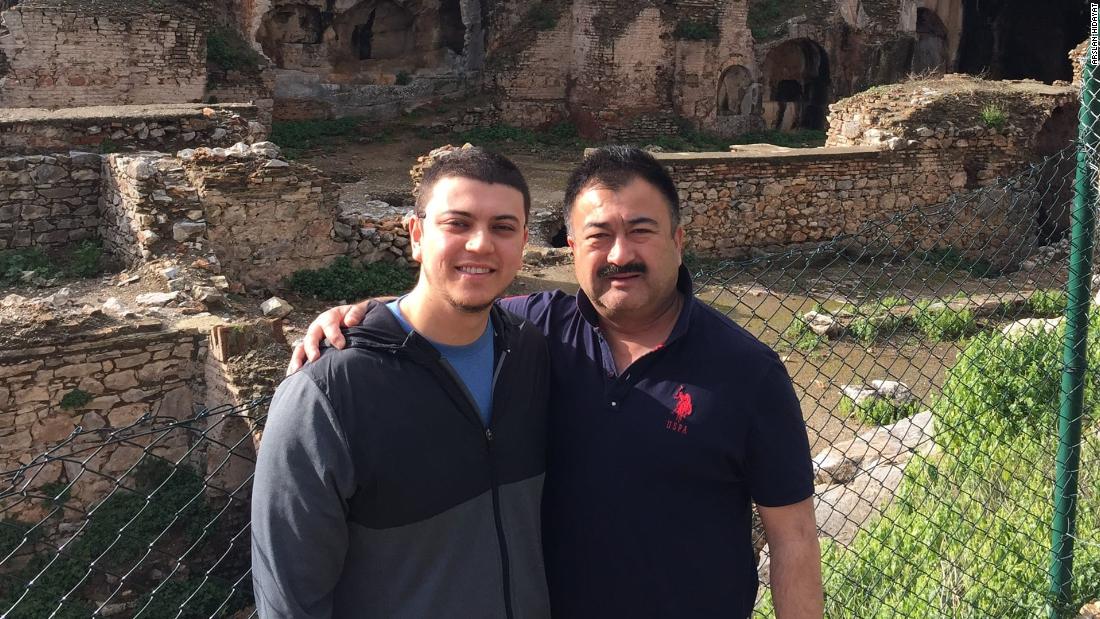

Arslan Hidayat (left) seen with his father-in-law, Uyghur comedian Adil Mijit, who the family say they have not heard from since November 2018.

The raid on Hidayat's page began at 8 p.m. in China.

Despite this, these sites appear to be becoming a key battleground of Chinese influence, as a growing army of Chinese assemble on forums and in Facebook groups to attack voices hostile to Beijing's interests.

Arslan Hidayat (left) seen with his father-in-law, Uyghur comedian Adil Mijit, who the family say they have not heard from since November 2018.

The raid on Hidayat's page began at 8 p.m. in China.

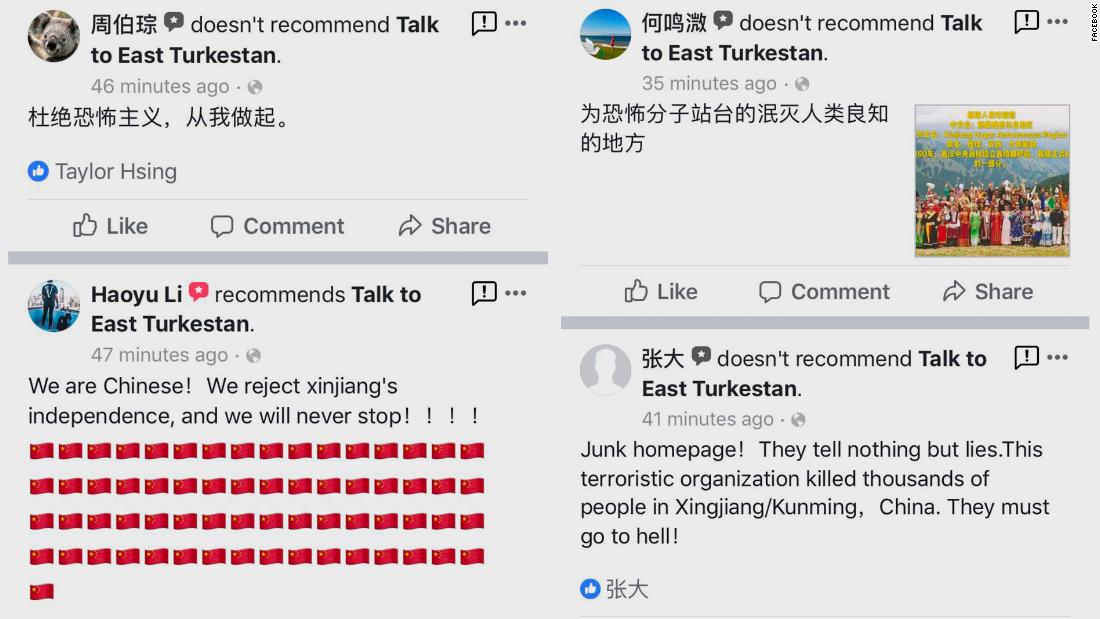

Photos and quotes at the ready, the Chinese began posting.

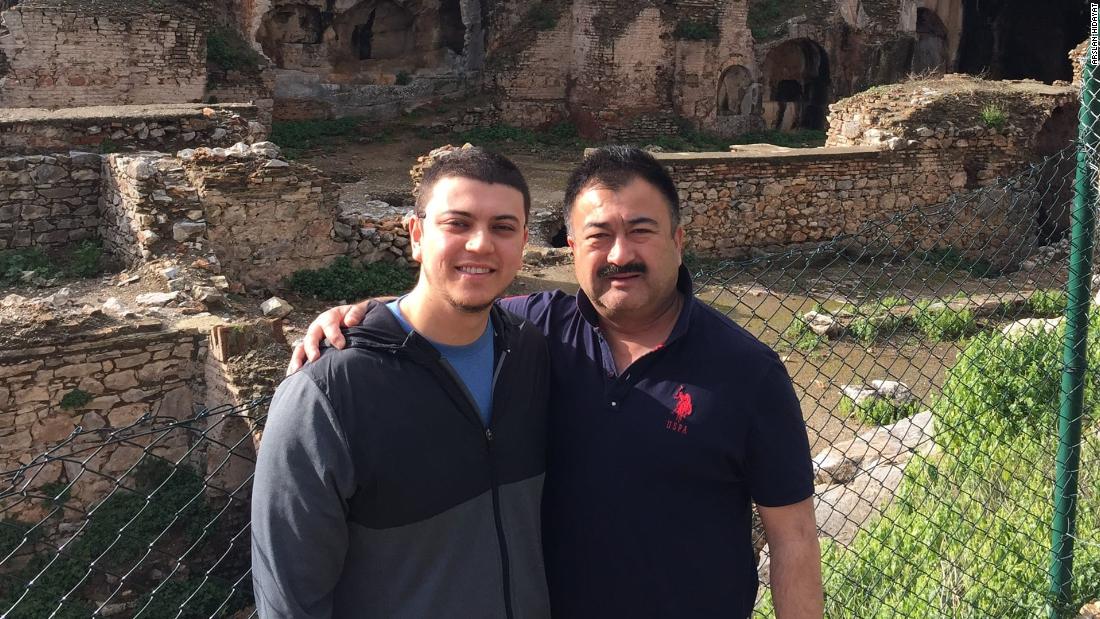

"We are Chinese! We reject East Turkestan's independence, and we will never stop!" read one message in English.

"East Turkestan has been China's territory since ancient times," said another.

(The colony's relationship with Beijing has changed considerably over time, and in the modern era it has been the subject of particular dispute. In the last century, following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, Uyghurs twice declared independence and created their own republics before the CCP took control of East Turkestan and declared it Chinese territory.)

The comments flooded the Facebook pages of TET and the Munich-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC), an exile group that receives funding from the National Endowment for Democracy, a Washington-linked group.

"We are Chinese! We reject East Turkestan's independence, and we will never stop!" read one message in English.

"East Turkestan has been China's territory since ancient times," said another.

(The colony's relationship with Beijing has changed considerably over time, and in the modern era it has been the subject of particular dispute. In the last century, following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, Uyghurs twice declared independence and created their own republics before the CCP took control of East Turkestan and declared it Chinese territory.)

The comments flooded the Facebook pages of TET and the Munich-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC), an exile group that receives funding from the National Endowment for Democracy, a Washington-linked group.

Photos posted alongside comments by the Chinese showed smiling Uyghurs, many in ethnic dress, with captions in Chinese and English such as "We live very well" or "East Turkestan sheep and cattle fat, we live well every day."

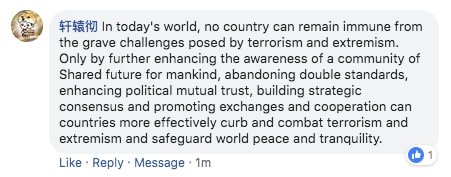

Other posts just quoted large blocks of text taken from speeches by Chinese dictator Xi Jinping or a Chinese white paper on the situation in East Turkestan.

The Chinese raid lasted for two hours — according to timestamps on posts and an announcement by organizers — with dozens of comments posted per minute in the busiest period, according to page administrators, who could do little but flag the posts to Facebook via automated tools.

"There was not much you could do in the middle of it except watch and try to alert people that it was happening," said Pete Irwin, a WUC researcher and an administrator of its Facebook page.

"There will be media screenshots of the process, don't lose face for yourself and your country," they said.

"We are only anti-extremist, not anti-religion or ethnicity, and everyone has their own freedom of belief. Please do not attack people or religion, and do not publish extreme rhetoric. Our purpose is national harmony and equality for all."

Speaking via instant messenger, an admin of one of the Facebook groups coordinating the raid said it had two primary purposes.

"The first one is to refute all the rumors about East Turkestan colony spread by the East Turkistan separatists," said the admin, who gave her name as Vicky.

The admin said while she was based in China, others involved in the campaign were overseas Chinese.

Even though most of the comments have since been deleted by page admins, Vicky felt it was a successful operation.

"I think we got our foot in the door," she said.

The Facebook raid comes amid what appears to be heightened concern within China over how the country is portrayed on Western social media.

In China, Twitter users critical of the government have reportedly been visited by the police and ordered to delete posts or their entire accounts.

Accounts of Chinese dissidents, and even non-political researchers, have gone silent without explanation.

Reddit administrators have also noticed a surge in threads relating to topics critical of China being downvoted and those maligning it being buried, according to BuzzFeed News.

The Cyberspace Administration of China did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

In a statement, China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that "as a principle, we don't normally comment on social media activities and opinions."

"Nowadays, the overall social situation of East Turkestan is stable and the momentum for economic development is good. All ethnic groups get along well," the foreign ministry said in its statement. "The sense of security and fulfillment from a stable society have improved greatly."

A Facebook spokeswoman told CNN the company was working "in a variety of ways to find and disrupt this kind of abuse and to provide people with the tools that help people control the content they see."

"In this case, we have removed content and accounts that violate our policies, and will continue to investigate and take action on any abusive behavior we find," she said.

"I think it speaks to a paranoia or anxiety" over how the East Turkestan issue is reflecting on China, Irwin said of the recent raid on the WUC Facebook page.

Hidayat agreed: "For them to go out of their way to attack in this manner, we felt very proud. It shows they're taking notice."

But he was also worried that the content used in the campaign, such as quotes from allegedly happy Uyghurs, could undermine the claims made by his organization.

"For those newbies just catching up to this issue ... the claims that we make and some of the stuff that is written looks far-fetched — people not being able to pray or fast — but it's true," he says.

Even in Turkey, with its large community of Uyghurs there are people who "don't even know what East Turkestan and the Uyghurs are," he says.

"But if East Turkestan was really (as) stable as they say it is then they wouldn't have gone out of their way to attack such a small page," Hidayat says.

As of this publication, his page has fewer than 20,000 followers.

In the wake of the attack, the TET Facebook page saw a spike in followers thanks to the extra media attention, adding around a thousand.

"It's all positive from our side," he says.

"I would like to thank the CCP for promoting our Facebook."

"There was not much you could do in the middle of it except watch and try to alert people that it was happening," said Pete Irwin, a WUC researcher and an administrator of its Facebook page.

"In the middle of it, comments were coming constantly."

Locating those responsible for the raid was not hard.

Many of the photos and comments referenced Diba, a popular online bulletin board akin to China's version of 4Chan, the notorious meme factory.

Photos featured Diba's logo, and many of those commenting changed their profile pictures to represent the forum.

Comments left on the Facebook page of Talk to East Turkestan during a raid by users of the Diba forum.

Football forum

Diba is a sub-forum of a Reddit-style offshoot of Baidu, China's biggest search engine.

The forum began as a place for fans of footballer Li Yi to hang out, but has since evolved into a sprawling, generalist forum of more than 31 million users, according to stats on the official Diba page.

That size has given Diba a huge influence on Chinese internet culture, experts say.

Any large groups organizing inside China are often liable to censorship or deletion by the CCP.

As Diba grew, it risked facing this type of control, but for the foresight of its moderators: In around 2014, according to a study of the forum, moderators worked to transform Diba into a pro-government forum, reducing some of its controversial content in favor of more nationalist topics and tighter standards.

Diba began to go after Beijing's enemies overseas, adopting a trolling tactic called brigading.

Known in Mandarin as baoba, or "bursting the board," in China, brigading is when members of one forum flood another with irrelevant or abusive posts with the aim of shutting the board down.

The tactic is popular with trolls on 4Chan and Reddit.

The latter has listed it as one of just three "prohibited behaviors."

Diba's first major international raid — or "expedition," as participants referred to it — was in January 2016, after the election of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen.

Tsai's Democratic Progressive Party is traditionally supportive of Taiwanese independence, and her election came amid heightened tensions between China and Taiwan, which the Communists view as a renegade province, to be reclaimed by force if necessary.

At 7 p.m. China time on January 20, thousands of comments against Taiwanese independence began flooding Tsai's Facebook page, as well as those of pro-Taiwanese news outlets Apple Daily and Sanlih News.

While many posts followed organizers' guidance to be "positive" in their trolling, there were plenty of posts during the raid insulting Tsai and Taiwan, telling Taiwanese people they "belonged to China" and warning them not to "talk back to your father."

Uyghur expedition

In many ways, according to admins and a study of the forum, the people behind the raid on the Facebook pages of Tsai Ing-wen and Hidayat are much like the Uyghur activist: tech savvy, highly-educated millennials.

But when it comes to their beliefs and values they are diametrically opposed.

Those involved in the raid believe the TET Facebook account is spreading lies, maligning China's reputation overseas and promoting separatism and even terrorism.

And they are determined to stop it.

But contrary to most stereotypes about internet trolls, they are committed to doing so without profanity or insults, for the most part.

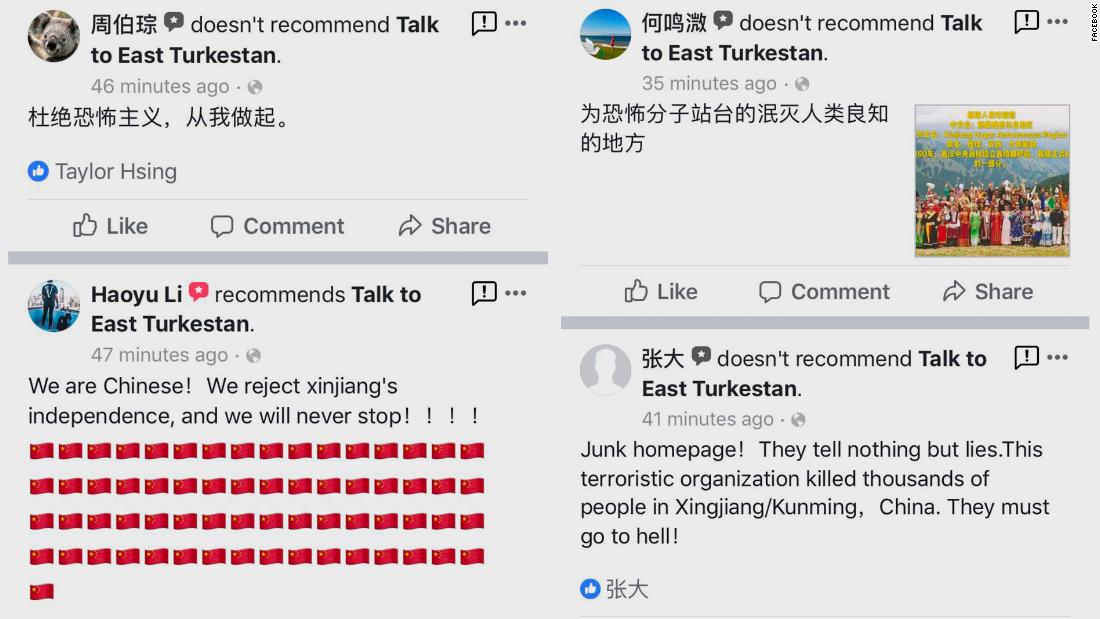

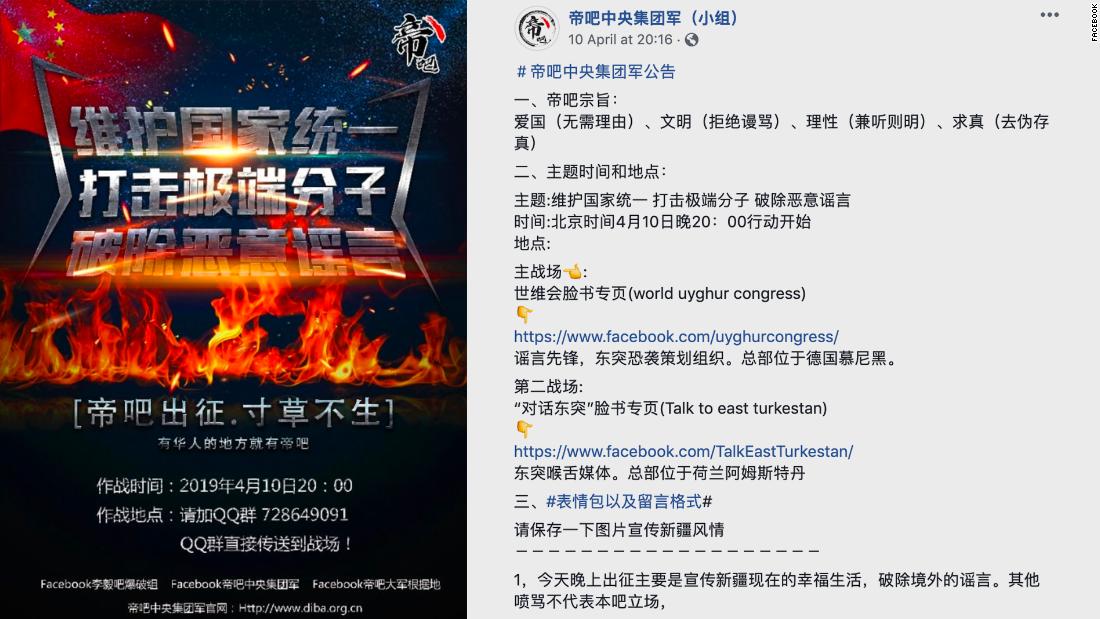

On Diba, Chinese social media site Weibo, and a handful of Facebook pages and groups, the instructions organizers posted for the raid included behavioral guidelines.

Guidelines given to Diba users listed the forum's four key principles: be patriotic, don't curse, be reasonable and maintain truth above all else.

Organizers appeared to be conscious that the raid would attract a global audience.

A poster and instructions for a raid organized against two Facebook pages by members of Diba, a Chinese forum.

Locating those responsible for the raid was not hard.

Many of the photos and comments referenced Diba, a popular online bulletin board akin to China's version of 4Chan, the notorious meme factory.

Photos featured Diba's logo, and many of those commenting changed their profile pictures to represent the forum.

Comments left on the Facebook page of Talk to East Turkestan during a raid by users of the Diba forum.

Football forum

Diba is a sub-forum of a Reddit-style offshoot of Baidu, China's biggest search engine.

The forum began as a place for fans of footballer Li Yi to hang out, but has since evolved into a sprawling, generalist forum of more than 31 million users, according to stats on the official Diba page.

That size has given Diba a huge influence on Chinese internet culture, experts say.

Any large groups organizing inside China are often liable to censorship or deletion by the CCP.

As Diba grew, it risked facing this type of control, but for the foresight of its moderators: In around 2014, according to a study of the forum, moderators worked to transform Diba into a pro-government forum, reducing some of its controversial content in favor of more nationalist topics and tighter standards.

Diba began to go after Beijing's enemies overseas, adopting a trolling tactic called brigading.

Known in Mandarin as baoba, or "bursting the board," in China, brigading is when members of one forum flood another with irrelevant or abusive posts with the aim of shutting the board down.

The tactic is popular with trolls on 4Chan and Reddit.

The latter has listed it as one of just three "prohibited behaviors."

Diba's first major international raid — or "expedition," as participants referred to it — was in January 2016, after the election of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen.

Tsai's Democratic Progressive Party is traditionally supportive of Taiwanese independence, and her election came amid heightened tensions between China and Taiwan, which the Communists view as a renegade province, to be reclaimed by force if necessary.

At 7 p.m. China time on January 20, thousands of comments against Taiwanese independence began flooding Tsai's Facebook page, as well as those of pro-Taiwanese news outlets Apple Daily and Sanlih News.

While many posts followed organizers' guidance to be "positive" in their trolling, there were plenty of posts during the raid insulting Tsai and Taiwan, telling Taiwanese people they "belonged to China" and warning them not to "talk back to your father."

Uyghur expedition

In many ways, according to admins and a study of the forum, the people behind the raid on the Facebook pages of Tsai Ing-wen and Hidayat are much like the Uyghur activist: tech savvy, highly-educated millennials.

But when it comes to their beliefs and values they are diametrically opposed.

Those involved in the raid believe the TET Facebook account is spreading lies, maligning China's reputation overseas and promoting separatism and even terrorism.

And they are determined to stop it.

But contrary to most stereotypes about internet trolls, they are committed to doing so without profanity or insults, for the most part.

On Diba, Chinese social media site Weibo, and a handful of Facebook pages and groups, the instructions organizers posted for the raid included behavioral guidelines.

Guidelines given to Diba users listed the forum's four key principles: be patriotic, don't curse, be reasonable and maintain truth above all else.

Organizers appeared to be conscious that the raid would attract a global audience.

A poster and instructions for a raid organized against two Facebook pages by members of Diba, a Chinese forum.

"There will be media screenshots of the process, don't lose face for yourself and your country," they said.

"We are only anti-extremist, not anti-religion or ethnicity, and everyone has their own freedom of belief. Please do not attack people or religion, and do not publish extreme rhetoric. Our purpose is national harmony and equality for all."

Speaking via instant messenger, an admin of one of the Facebook groups coordinating the raid said it had two primary purposes.

"The first one is to refute all the rumors about East Turkestan colony spread by the East Turkistan separatists," said the admin, who gave her name as Vicky.

The admin said while she was based in China, others involved in the campaign were overseas Chinese.

Even though most of the comments have since been deleted by page admins, Vicky felt it was a successful operation.

"I think we got our foot in the door," she said.

The Facebook raid comes amid what appears to be heightened concern within China over how the country is portrayed on Western social media.

In China, Twitter users critical of the government have reportedly been visited by the police and ordered to delete posts or their entire accounts.

Accounts of Chinese dissidents, and even non-political researchers, have gone silent without explanation.

Reddit administrators have also noticed a surge in threads relating to topics critical of China being downvoted and those maligning it being buried, according to BuzzFeed News.

The Cyberspace Administration of China did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

In a statement, China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that "as a principle, we don't normally comment on social media activities and opinions."

"Nowadays, the overall social situation of East Turkestan is stable and the momentum for economic development is good. All ethnic groups get along well," the foreign ministry said in its statement. "The sense of security and fulfillment from a stable society have improved greatly."

A Facebook spokeswoman told CNN the company was working "in a variety of ways to find and disrupt this kind of abuse and to provide people with the tools that help people control the content they see."

"In this case, we have removed content and accounts that violate our policies, and will continue to investigate and take action on any abusive behavior we find," she said.

Hidayat agreed: "For them to go out of their way to attack in this manner, we felt very proud. It shows they're taking notice."

But he was also worried that the content used in the campaign, such as quotes from allegedly happy Uyghurs, could undermine the claims made by his organization.

"For those newbies just catching up to this issue ... the claims that we make and some of the stuff that is written looks far-fetched — people not being able to pray or fast — but it's true," he says.

Even in Turkey, with its large community of Uyghurs there are people who "don't even know what East Turkestan and the Uyghurs are," he says.

"But if East Turkestan was really (as) stable as they say it is then they wouldn't have gone out of their way to attack such a small page," Hidayat says.

As of this publication, his page has fewer than 20,000 followers.

In the wake of the attack, the TET Facebook page saw a spike in followers thanks to the extra media attention, adding around a thousand.

"It's all positive from our side," he says.

"I would like to thank the CCP for promoting our Facebook."

Abdikadir Yasin, a Uighur Muslim from China seeking asylum in Sweden, with his wife and one of their children in emergency housing in the city of Gävle.

Abdikadir Yasin, a Uighur Muslim from China seeking asylum in Sweden, with his wife and one of their children in emergency housing in the city of Gävle.

Abdusalam Muhemet, 41, with his children at his home in Istanbul. The family sought refuge in Turkey after Mr. Muhemet was released from one of China’s indoctrination camps for Uighurs and other Muslims.

Abdusalam Muhemet, 41, with his children at his home in Istanbul. The family sought refuge in Turkey after Mr. Muhemet was released from one of China’s indoctrination camps for Uighurs and other Muslims.