Inside Chinese food industry frauds and malpractices

Bloomberg News

A bowl of ice cream on a hot day in Shanghai gave American Mitchell Weinberg the worst bout of food poisoning he can recall.

It also inspired the then-trade consultant to set up Inscatech — a global network of food spies.

In demand by multinational retailers and food producers, Inscatech and its agents scour supply chains around the world hunting for evidence of food industry fraud and malpractice.

In demand by multinational retailers and food producers, Inscatech and its agents scour supply chains around the world hunting for evidence of food industry fraud and malpractice.

In the eight years since he founded the New York-based firm, Weinberg, 52, says China continues to be a key growth area for fraudsters as well as those developing technologies trying to counter them.

“Statistically we’re uncovering fraud about 70 percent of the time, but in China it’s very close to 100 percent,” he said.

“Statistically we’re uncovering fraud about 70 percent of the time, but in China it’s very close to 100 percent,” he said.

“It’s pervasive, it’s across food groups, and it’s anything you can possibly imagine.”

Police inspect illegal cooking oil, or "gutter oil," seized during a crackdown in Beijing in Aug. 2010.

Police inspect illegal cooking oil, or "gutter oil," seized during a crackdown in Beijing in Aug. 2010.

While adulteration has been a bugbear of consumers since prehistoric wine was first diluted with saltwater, scandals in China over the past decade — from melamine-laced baby formula, to rat-meat dressed as lamb — have seen the planet’s largest food-producing and consuming nation become a hotbed of corrupted, counterfeit, and contaminated food.

Weinberg’s company is developing molecular markers and genetic fingerprints to help authenticate natural products and sort genuine foodstuffs from the fakes.

Weinberg’s company is developing molecular markers and genetic fingerprints to help authenticate natural products and sort genuine foodstuffs from the fakes.

Another approach companies are pursuing uses digital technology to track and record the provenance of food from farm to plate.

“Consumers want to know where products are from,” said Shaun Rein, managing director of China Market Research Group, citing surveys the Shanghai-based consultancy conducted with consumers and supermarket operators.

“Consumers want to know where products are from,” said Shaun Rein, managing director of China Market Research Group, citing surveys the Shanghai-based consultancy conducted with consumers and supermarket operators.

‘Business Opportunity’

Services that help companies mitigate the reputational risk that food-fraud poses is a “big growth area,” according to Rein.

“It’s a great business opportunity,” he said.

“It’s going to be important not just as a China play, but as a global play, because Chinese food companies are becoming part of the whole global supply chain.”

Some of the biggest food companies are backing technology that grew out of the anarchic world of crypto-currencies.

Some of the biggest food companies are backing technology that grew out of the anarchic world of crypto-currencies.

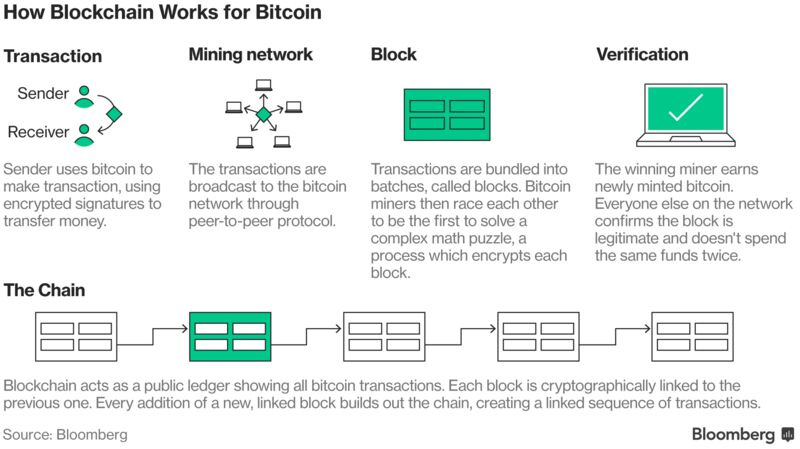

It’s called blockchain, essentially a shared, cryptographically secure ledger of transactions.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc., the world’s largest retailer, was one of the first to get on board, just completing a trial using blockchain technology to track pork in China, where it has more than 400 stores.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc., the world’s largest retailer, was one of the first to get on board, just completing a trial using blockchain technology to track pork in China, where it has more than 400 stores.

The time taken to track the meat’s supply chain was cut from 26 hours to just seconds using blockchain, and the scope of the project is being widened to other products, said Frank Yiannas, Wal-Mart’s vice president for food safety, in an interview Thursday.

Shanghai-based Zhong An Information and Technology Services Co. said in June it will use the technology to track chickens from the coop to the processing facility and on to the market or store.

Shanghai-based Zhong An Information and Technology Services Co. said in June it will use the technology to track chickens from the coop to the processing facility and on to the market or store.

Blockchain Pilot

Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., too, sees the potential for the eight-year-old technology to provide greater product integrity across its platforms, which accounted for more then 75 percent of China’s online retail sales in 2015.

The planned blockchain project will involve the Chinese e-commerce behemoth working with food suppliers in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Australia Post and auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

“Food fraud is a serious global issue,” said Maggie Zhou, managing director for Alibaba in Australia and New Zealand.

“Food fraud is a serious global issue,” said Maggie Zhou, managing director for Alibaba in Australia and New Zealand.

“This project is the first step in creating a globally respected framework that protects the reputation of food merchants and gives consumers further confidence to purchase food online.”

Fraud costs the global food industry as much as $40 billion annually, according to John Spink, director of Michigan State University’s Food Fraud Initiative.

In China, where the 2008 melamine milk crisis resulted in the death of at least six babies, it’s a hot-button issue compounded by the country’s growing appetite for higher quality food and swelling middle class.

A Pew Research Center study last year found 40 percent of Chinese view food safety as a “very big problem,” up from 12 percent in 2008.

“What we have to do is reinforce our regulations to improve the transparency of the administration, for example information-sharing,” said Yongguan Zhu, director general of the Institute of Urban Environment, part of the state-funded Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Farmers pour away unsold milk in Hebei Province in Sept. 2008.

Zhu says blockchain could play an important role in improving traceability.

Farmers pour away unsold milk in Hebei Province in Sept. 2008.

Zhu says blockchain could play an important role in improving traceability.

Its database of records can be built like a chain and can’t be broken or re-ordered without disrupting the entire connection.

Last month, Beijing emphasized to authorities the need to be upfront in disclosing food safety issues.

“Food-fraud will always exist,” said Yongning Wu, chief scientist at the government-run China National Center For Food Safety Risk Assessment.

Wu doesn’t see the problem disappearing.

“We can only develop technology to detect it,” he said.

“We can only develop technology to detect it,” he said.

“However, fake-food producers will always update their technology to dodge inspections.”

Wily Scammers

The wiliness of fraudsters is what makes Inscatech’s Weinberg less hopeful about blockchain.

His firm mainly uses informants on the ground to sniff out where in the production process food-fraud is taking place, and most of his work in China is with western companies that manufacture or source product there.

Counterfeit liquor is tested at the Beijing administration for industry and commerce center in June 2007.

“The problem is the data is only as reliable as the person providing the data,” said Weinberg, who recalls seeing everything in China from synthetic eggs to fake shrimp that still sizzle in a wok.

Counterfeit liquor is tested at the Beijing administration for industry and commerce center in June 2007.

“The problem is the data is only as reliable as the person providing the data,” said Weinberg, who recalls seeing everything in China from synthetic eggs to fake shrimp that still sizzle in a wok.

“In most supply chains there is one or more ‘unreliable’ data provider. This means blockchain is likely useless for protecting against food-fraud unless every piece of data is scrutinized to be accurate.”

A months-long Bloomberg investigation into the global shrimp trade last year showed how unreliable documentation had fanned an illegal transhipping scheme involving Chinese aquaculture exporters.

But blockchain is “light years” away from the system used by the global food industry today, which relies heavily on paper records, said Yiannas, Wal-Mart’s food safety chief.

But blockchain is “light years” away from the system used by the global food industry today, which relies heavily on paper records, said Yiannas, Wal-Mart’s food safety chief.

By recording the identity of those who input data into the chain, the technology removes the anonymity that has helped food-fraud to thrive, he said.

The role of humans in recording the supply chain will also diminish, said Yiannas.

The role of humans in recording the supply chain will also diminish, said Yiannas.

“More and more of these documents will eventually be captured in an automated way.”

China’s Food and Drug Administration didn’t immediately respond to an email requesting comment on the country’s food safety efforts.

Some companies are already bringing traceability to consumers.

Fonterra Cooperative Group Ltd., the world’s biggest dairy exporter, started putting QR codes on cans of infant formula in April, enabling buyers to verify the product’s authenticity.

Criminal Factor

The challenges for China — “the factory of the world” — are especially vast because of its size, population, multilayered administrative divisions, and “the willingness of criminals to exploit every corner that they can in order to make money,” said Michael Ellis, who ran Interpol’s trafficking in illicit goods unit until October.

At Interpol, Ellis, a former detective with Scotland Yard in London, was involved in “Opson,” an operation that led to the seizure of more than 10,000 tons and 1 million liters (264,000 gallons) of hazardous fake-food and drinks across more than 50 countries.

Without a presence to fight it, food-fraud globally “will explode,” Ellis said.

“It will just continue to grow, and who knows where it will lead.”