In Hotan, documents show officials are expanding detention camps and increasing surveillance

by Lily Kuo in LuopuThe Luopu County No 1 Vocational Skills Training Centre is hard to miss.

It emerges suddenly, a huge campus towering over hectares of farmland.

Outside the compound, surrounded by tall white concrete walls lined with barbed wire and surveillance cameras, a police car patrols while several guards carrying long batons stand watch.

Outside the compound, surrounded by tall white concrete walls lined with barbed wire and surveillance cameras, a police car patrols while several guards carrying long batons stand watch.

The centre, which straddles a highway, is bigger than most of the surrounding villages – about 170,000sq metres.

A banner on one building says: “Safeguard ethnic unity.”

Half a dozen people stand on the roadside, staring at the buildings.

Half a dozen people stand on the roadside, staring at the buildings.

No one is willing to say exactly what this prison-like facility is or why they are waiting on its perimeter.

“We don’t know,” says an older woman.

Uighur leaders say China's actions are precursors to genocide

A starkly different reality emerges in Luopu, also known as Lop county, where Guardian interviews with current and former residents and analysis of public documents reveal new details about the government’s continuing campaign in one of the worst-affected areas of East Turkestan.

Local authorities are expanding detention camps, increasing surveillance and policing, and co-opting residents through intimidation, force and financial incentives.

The cost of ‘stability control’

In the past year, at least 10 buildings have been added to the No 1 Vocational Skills Training Centre, according to satellite imagery.

In 2018, officials expected to accommodate 12,000 “students” as well as another 2,100 inmates at another detention centre – a total of about 7% of the county’s adult population, or 11% of the entire male population.

Luopu county also planned to spend almost 300m yuan ($44m) on “stability control”, including almost $300,000 on a surveillance system to cover all mosques, and funding for almost 6,000 police officers to work in “convenient police stations” and security checkpoints, as well as to patrol residential areas.

The security measures and staggering costs underline China’s commitment to its controversial policies in East Turkestan despite growing criticism.

Across the province, domestic security expenses doubled in 2017 as the security campaign got under way, with spending on detention centres in counties with large concentrations of ethnic minorities quadrupling, according to Adrian Zenz, a researcher focused on China’s ethnic policies.

Budget overruns were common.

‘Don’t come here’

Today, Hotan prefecture is under “grid style” management, involving intense policing and mass surveillance.

‘Red star’ households

In a village in Luopu county, almost every home has a plaque on the door marking it a “model red star family”.

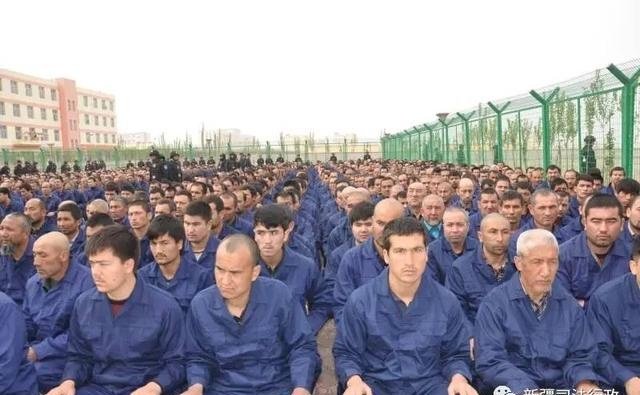

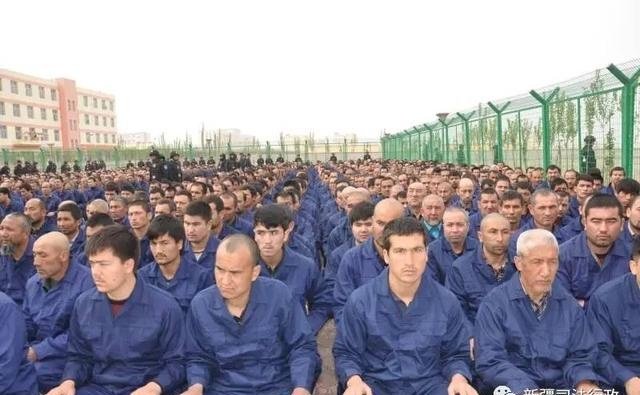

Images of East Turkestan, China, taken in December as part of a Guardian investigation into the mass detention of Uighur Muslims in China.

“We don’t know,” says an older woman.

Another woman has come to see her brother but declines to say more.

A young girl with her two brothers announces they have come to see their father.

Her mother quickly hushes her.

They are reluctant to talk because the building is not a formal prison or university, but an internment camp where Muslim minorities, mainly Uighurs, are sent against their will and without trial for months or even years.

Researchers and residents say East Turkestan, where the Luopu County No 1 Vocational Skills Training Centre is located, has borne the brunt of the government’s crackdown on Muslims because of its density of Uighurs and distance from major cities.

“We have a saying in Hotan: If you go into a concentration camp in Luopu, you never come out,” said Adil Awut*, from Hotan City, who is now living overseas.

In December, the United Nations asked for direct access to the camps after a panel said it had received “credible reports” that 1.1 million Uighurs, Kazakhs, Hui and other ethnic minorities had been detained.

Beijing has aggressively defended its policies and sought to portray the camps as benign and East Turkestan, where outbursts of violence occurred in the 1990s and 2000s, as peaceful thanks to government efforts.

They are reluctant to talk because the building is not a formal prison or university, but an internment camp where Muslim minorities, mainly Uighurs, are sent against their will and without trial for months or even years.

Researchers and residents say East Turkestan, where the Luopu County No 1 Vocational Skills Training Centre is located, has borne the brunt of the government’s crackdown on Muslims because of its density of Uighurs and distance from major cities.

“We have a saying in Hotan: If you go into a concentration camp in Luopu, you never come out,” said Adil Awut*, from Hotan City, who is now living overseas.

In December, the United Nations asked for direct access to the camps after a panel said it had received “credible reports” that 1.1 million Uighurs, Kazakhs, Hui and other ethnic minorities had been detained.

Beijing has aggressively defended its policies and sought to portray the camps as benign and East Turkestan, where outbursts of violence occurred in the 1990s and 2000s, as peaceful thanks to government efforts.

Uighur leaders say China's actions are precursors to genocide

A starkly different reality emerges in Luopu, also known as Lop county, where Guardian interviews with current and former residents and analysis of public documents reveal new details about the government’s continuing campaign in one of the worst-affected areas of East Turkestan.

Local authorities are expanding detention camps, increasing surveillance and policing, and co-opting residents through intimidation, force and financial incentives.

The cost of ‘stability control’

In the past year, at least 10 buildings have been added to the No 1 Vocational Skills Training Centre, according to satellite imagery.

Construction work on the camp, identified through company records found by the University of British Columbia student Shawn Zhang, was still being carried out when the Guardian visited in mid-December.

Luopu, a sparsely populated rural county of about 280,000 that is almost entirely Uighur, is home to eight internment camps officially labelled “vocational training centres”, according to public budget documents seen by the Guardian.

Luopu, a sparsely populated rural county of about 280,000 that is almost entirely Uighur, is home to eight internment camps officially labelled “vocational training centres”, according to public budget documents seen by the Guardian.

Police patrol the Old Town in Kashgar, to the west of Luopu county.

In 2018, officials expected to accommodate 12,000 “students” as well as another 2,100 inmates at another detention centre – a total of about 7% of the county’s adult population, or 11% of the entire male population.

Luopu county also planned to spend almost 300m yuan ($44m) on “stability control”, including almost $300,000 on a surveillance system to cover all mosques, and funding for almost 6,000 police officers to work in “convenient police stations” and security checkpoints, as well as to patrol residential areas.

The security measures and staggering costs underline China’s commitment to its controversial policies in East Turkestan despite growing criticism.

Across the province, domestic security expenses doubled in 2017 as the security campaign got under way, with spending on detention centres in counties with large concentrations of ethnic minorities quadrupling, according to Adrian Zenz, a researcher focused on China’s ethnic policies.

Budget overruns were common.

Luopu county exceeded its budget by almost 300% in 2017, the highest increase in spending in all of Hotan prefecture.

Yet, the buildup continues.

Yet, the buildup continues.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute analysed 28 camps across East Turkestan and found they had expanded 465% in size since 2016, with the largest growth between July and September last year. Five camps in Hotan city and surrounding counties had at least doubled in size, with one camp increasing 2,469% between 2016 and 2018.

In Luopu, officials are bringing more than 2,700 assistant officers into the county’s 224 villages and townships.

In Luopu, officials are bringing more than 2,700 assistant officers into the county’s 224 villages and townships.

The “students” are closely monitored: almost 2,000 staff and police have been hired to oversee 12,000 detainees.

Authorities are also spending money on incentivising residents.

Authorities are also spending money on incentivising residents.

Officials in Luopu hire local imams and other religious leaders as “patriotic religious people”, paid a yearly stipend of 4,200 yuan (about $600) in an area where average disposable income is 6,800 yuan a year.

Their job is in part to stop residents from going on non-government organised pilgrimages to Mecca.

The relatively low-level assistant police, recruited mostly from Uighur communities, are paid 4,100 yuan a month, almost on a par with police in major cities.

Some local governments are struggling to maintain this pace of spending.

The relatively low-level assistant police, recruited mostly from Uighur communities, are paid 4,100 yuan a month, almost on a par with police in major cities.

Some local governments are struggling to maintain this pace of spending.

In neighbouring Cele county, where authorities expected to have almost 12,000 detainees in "vocational" camps and detention centres, a budget for 2018 says: “There are still many projects not included in the budget due to a lack of funds. The financial situation in 2018 is very severe.”

As China’s economy slows, they may struggle even more.

As China’s economy slows, they may struggle even more.

Zenz said: “The sustainability of this system basically depends on the financial capabilities of the central government … The long-term financial sustainability of all these top-down measures is certainly questionable.”

‘Don’t come here’

Today, Hotan prefecture is under “grid style” management, involving intense policing and mass surveillance.

On the Luopu government website, it is described as “often in a state of level one or two response”, the highest state of emergency.

In Luopu, like many places in East Turkestan, the movements of Uighur residents are restricted. While Han Chinese are waved through security checkpoints, Uighur commuters register their ID cards, do full body scans, have their vehicles searched and their faces scanned.

In Luopu, like many places in East Turkestan, the movements of Uighur residents are restricted. While Han Chinese are waved through security checkpoints, Uighur commuters register their ID cards, do full body scans, have their vehicles searched and their faces scanned.

CCTV monitoring on a street corner in Luopu county.

Hand-held devices scan smartphones for content deemed problematic.

A police officer demanded to check the phone of a Guardian reporter because, she said “someone saw Arabic or Uighur language on it”.

Abdulla Erkin*, born and raised in Luopu county, was living in Urumqi, in the north of East Turkestan, when the crackdown began in earnest.

Abdulla Erkin*, born and raised in Luopu county, was living in Urumqi, in the north of East Turkestan, when the crackdown began in earnest.

He says his family warned him not to return. “They all told me: ‘Don’t come here. Don’t come here. Just live in Urumqi.’”

His sister, who works in a local government bureau in Luopu told him: “It’s worse day after day.”

Erkin says most of his friends have been sent to a camp or prison.

Erkin says most of his friends have been sent to a camp or prison.

Now living overseas, he discovered last month that two of his brothers had been detained, and he fears five of his nephews have also gone.

A Uighur businessman living in north-eastern China told the Guardian he left Hotan because of the constant threat of being detained.

“My sense as well is that the counties of Hotan prefecture have been the target of most severe repression,” said Darren Byler, a lecturer at the University of Washington who has been focusing on East Turkestan.

“My sense as well is that the counties of Hotan prefecture have been the target of most severe repression,” said Darren Byler, a lecturer at the University of Washington who has been focusing on East Turkestan.

“From the perspective of the state, Hotan is framed as the most ‘backward and resistant’.”

Chinese officials have said international observers are “welcome to East Turkestan”, but Guardian reporters were questioned by police in Luopu for four hours and followed by at least seven people in Hotan City.

An official at the police station adjoining the No 1 Vocational Training Centre told the Guardian “all reporters, foreign or Chinese, from outside East Turkestan” were subject to their security measures.

Chinese officials have said international observers are “welcome to East Turkestan”, but Guardian reporters were questioned by police in Luopu for four hours and followed by at least seven people in Hotan City.

An official at the police station adjoining the No 1 Vocational Training Centre told the Guardian “all reporters, foreign or Chinese, from outside East Turkestan” were subject to their security measures.

‘Red star’ households

In a village in Luopu county, almost every home has a plaque on the door marking it a “model red star family”.

These are families who have met requirements, including demonstrating “anti-extremism thought” and a “sense of modern civilisation”.

Over the past year, Luopu local officials have gathered villagers to sing patriotic songs, a practice common in the camps, or to teach female residents how to be “good new era women” who promote “ideological emancipation”.

But it’s not clear that these initiatives are what have inspired obedience.

A woman burning a pile of branches lists people in her family who have been sent “to training”, including her 16-year-old son.

Over the past year, Luopu local officials have gathered villagers to sing patriotic songs, a practice common in the camps, or to teach female residents how to be “good new era women” who promote “ideological emancipation”.

But it’s not clear that these initiatives are what have inspired obedience.

A woman burning a pile of branches lists people in her family who have been sent “to training”, including her 16-year-old son.

Another woman says her husband has been in training in a different village since December 2017. She doesn’t know why he was sent.

“We have always been farmers,” she says.

A man carrying plastic bags of naan and skewers explains that his neighbour has gone to the training centre.

A man carrying plastic bags of naan and skewers explains that his neighbour has gone to the training centre.

He suddenly interrupts himself: “We are scared talking with you.”

He says: “They will retaliate.”

* Name has been changed to protect the identity of the interviewee

* Name has been changed to protect the identity of the interviewee