By Steven Lee Myers

In a painting touring museums across China, Xi Jinping is front and center while a statue of Deng Xiaoping is a distant image.

SHENZHEN, China — Shortly after taking over as China’s leader, Xi Jinping made a pilgrimage to lay a wreath at a large bronze monument to one of his predecessors, the man credited with ushering in the country’s new era of capitalist prosperity 40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping.

Xi’s gesture here in the southern city of Shenzhen was hardly remarkable.

SHENZHEN, China — Shortly after taking over as China’s leader, Xi Jinping made a pilgrimage to lay a wreath at a large bronze monument to one of his predecessors, the man credited with ushering in the country’s new era of capitalist prosperity 40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping.

Xi’s gesture here in the southern city of Shenzhen was hardly remarkable.

Deng is second only to Mao in the pantheon of Communist China’s founding fathers, and his influence and popularity lingered long after his death in 1997.

Every Chinese leader since has sought to position himself as heir to Deng’s legacy.

Xi, though, now appears to be taking a different approach.

A large painting of his visit to the monument is touring museums across China ahead of the December anniversary of the Communist Party leadership meeting that Deng used to inaugurate the country’s “reform and opening up.”

Xi, though, now appears to be taking a different approach.

A large painting of his visit to the monument is touring museums across China ahead of the December anniversary of the Communist Party leadership meeting that Deng used to inaugurate the country’s “reform and opening up.”

In it, Xi stands front and center, while Deng’s statue is a distant image receding into a golden sunset.

It is the latest example of what some observers see as a concerted effort to elevate Xi’s role in the party’s official history, largely at Deng’s expense — a propaganda shift that could have a profound impact on Chinese politics and policymaking.

It is the latest example of what some observers see as a concerted effort to elevate Xi’s role in the party’s official history, largely at Deng’s expense — a propaganda shift that could have a profound impact on Chinese politics and policymaking.

Xi has been the focus of a lavish, highly choreographed multimedia campaign that is a throwback to Mao’s cult of personality.

Xi has not sought to erase Deng entirely.

Xi has not sought to erase Deng entirely.

He traveled to southern China last month on a visit with deliberate echoes of Deng’s famous 1992 tour of the region, for example.

Deng’s stature has been diminished, however, as Xi has centralized power and enhanced his own image with a lavish, highly choreographed multimedia campaign that critics have derided as a throwback to Mao’s cult of personality.

“Xi certainly isn’t content to operate in Deng’s shadow,” said Julian B. Gewirtz, a scholar at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard, adding that Xi wanted to “establish a distinctive political system with himself at the center.”

Mr. Gewirtz noted that Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, owed their positions and political legitimacy to Deng.

“Xi certainly isn’t content to operate in Deng’s shadow,” said Julian B. Gewirtz, a scholar at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard, adding that Xi wanted to “establish a distinctive political system with himself at the center.”

Mr. Gewirtz noted that Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, owed their positions and political legitimacy to Deng.

Xi, by contrast, rose to national prominence only after Deng’s death and is the first Chinese leader to take power without having been elevated by Deng into the party’s top ranks.

Still, Deng’s legacy represents both a challenge to and a potential constraint on Xi — a historical yardstick by which he is being measured, and a source of tradition that others in the party can use to limit Xi’s options.

In many ways, Xi has favored policies that depart from Deng’s agenda.

Still, Deng’s legacy represents both a challenge to and a potential constraint on Xi — a historical yardstick by which he is being measured, and a source of tradition that others in the party can use to limit Xi’s options.

In many ways, Xi has favored policies that depart from Deng’s agenda.

In addition to self-aggrandizing propaganda, which Deng eschewed, Xi has pressed a more assertive foreign policy that openly challenges the United States, worked to limit Western influence on Chinese society and sought to shield Chinese companies from foreign competition.

Xi has relegated his predecessors, including Hu Jintao, left, and Jiang Zemin, right, to transitional roles in the party’s official history.

Xi has also removed constitutional term limits on the presidency, prompting many Chinese to quote Deng’s warning from 1980 that “tenure for life” could only corrupt party leaders — a dig at Xi that was censored as quickly as it appeared online.

More recently, a speech by Deng’s influential son, Deng Pufang, at the annual congress of the China Disabled Persons’ Federation in September has attracted attention because portions of it were viewed as an oblique critique of Xi’s far-reaching ambitions.

“We must always maintain a pragmatic attitude and a clear mind,” said Deng, who was paralyzed in an attack during the Cultural Revolution and serves as chairman of the federation.

“We should be neither overconfident nor belittle ourselves.”

Xi has consolidated his position as China’s supreme leader and appears to face no significant political rival.

Xi has consolidated his position as China’s supreme leader and appears to face no significant political rival.

After a summer of discontent over the threat of a protracted trade war with the United States and pushback against the infrastructure investments at the heart of his Belt and Road Initiative, Xi has reasserted his place atop the political system.

The coming anniversary of the reforms associated with Deng remains fraught for Xi, however, because the nation’s direction under his leadership continues to draw unfavorable comparisons to Deng’s “hide your strength, bide your time” approach — at least among some liberal-minded analysts and officials.

The coming anniversary of the reforms associated with Deng remains fraught for Xi, however, because the nation’s direction under his leadership continues to draw unfavorable comparisons to Deng’s “hide your strength, bide your time” approach — at least among some liberal-minded analysts and officials.

Deng Xiaoping, shown here on his famous 1992 tour of southern China, has been second only to Mao in the Chinese Communist pantheon.

The party celebrated the 30th anniversary with great fanfare in 2008, but official plans to commemorate the 40th anniversary this year have been scaled back considerably, according to a veteran journalist with a state news outlet.

The party celebrated the 30th anniversary with great fanfare in 2008, but official plans to commemorate the 40th anniversary this year have been scaled back considerably, according to a veteran journalist with a state news outlet.

“Once you dredge up these matters, it’s very easy to lose control and set off new debate,” the journalist said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

During Xi’s visit to southern China last month, he noted the coming anniversary, attended an exhibition devoted to it and vowed to continue the economic transition that Deng began, but did not mention Deng — at least in the remarks chronicled by the state news media.

Inevitably, many compared the trip to the famous “southern tour” in 1992 that Deng used to steer the nation back toward market-oriented policies and out of the diplomatic isolation and economic retrenchment that followed the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

“Xi Jinping has been pickpocketing policies from the Deng era,” Geremie R. Barmé, an Australian scholar of China, wrote this summer.

During Xi’s visit to southern China last month, he noted the coming anniversary, attended an exhibition devoted to it and vowed to continue the economic transition that Deng began, but did not mention Deng — at least in the remarks chronicled by the state news media.

Inevitably, many compared the trip to the famous “southern tour” in 1992 that Deng used to steer the nation back toward market-oriented policies and out of the diplomatic isolation and economic retrenchment that followed the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

“Xi Jinping has been pickpocketing policies from the Deng era,” Geremie R. Barmé, an Australian scholar of China, wrote this summer.

“He does so while diminishing the man hailed for decades as the ‘Architect of Reform and the Opening Door Policies.’ At the same, he crucially overrides aspects of Deng’s legacy that might limit his afflatus and sense of mission.”

Mr. Barmé, in an interview, said Xi was eager to position himself as “the greater unifier after Mao,” relegating Deng and the leaders who followed him to an era of economic transition leading to a new era of strength that only he can achieve.

Mr. Barmé, in an interview, said Xi was eager to position himself as “the greater unifier after Mao,” relegating Deng and the leaders who followed him to an era of economic transition leading to a new era of strength that only he can achieve.

Tellingly, Xi’s trip included a visit to China’s southern military command, where he urged commanders “to strengthen the mission” and focus on “preparations for fighting a war.”

Xi visited this statue of Deng in Shenzhen soon after taking power but has departed from Deng’s agenda.

The painting of Xi visiting the monument to Deng is part of an exhibition that first appeared in Beijing and then in the southern province of Guangdong.

It covers the 40 years of “reform and opening up,” but Deng appears clearly in only one painting — seated, smoking a cigarette and listening to a lecture by the party secretary of Guangdong, Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun.

“We all know that Deng Xiaoping is, of course, the helmsman, a very great figure, but many people don’t know that Comrade Xi Zhongxun is also being studied by a lot of people nowadays,” said Fan Bo, an artist who was commissioned to create a portrait of the elder Xi for the exhibition.

It shows Xi’s father, his pants rolled up, bathed in a ray of light through the clouds, speaking with workers on the site of Shenzhen’s first special economic zone.

“We all know that Deng Xiaoping is, of course, the helmsman, a very great figure, but many people don’t know that Comrade Xi Zhongxun is also being studied by a lot of people nowadays,” said Fan Bo, an artist who was commissioned to create a portrait of the elder Xi for the exhibition.

It shows Xi’s father, his pants rolled up, bathed in a ray of light through the clouds, speaking with workers on the site of Shenzhen’s first special economic zone.

Fan titled the painting “First Steps.”

“It’s an objective restoration of the historical fact,” he said.

Others are pushing back against efforts to diminish Deng’s legacy.

“Chinese society today is a result of Deng’s reform and opening up,” wrote Sheng Hong, the director of the Unirule Institute of Economics, in a recent essay.

“It’s an objective restoration of the historical fact,” he said.

Others are pushing back against efforts to diminish Deng’s legacy.

“Chinese society today is a result of Deng’s reform and opening up,” wrote Sheng Hong, the director of the Unirule Institute of Economics, in a recent essay.

“There is a countercurrent at the moment. However, it should not be very difficult to resist the countercurrent and maintain Deng’s vision for further reform and opening up.”

On Monday, Sheng said on Twitter that he was told not to attend a conference at Harvard devoted to the anniversary and Deng’s legacy on the grounds that it would “endanger national security.”

On Monday, Sheng said on Twitter that he was told not to attend a conference at Harvard devoted to the anniversary and Deng’s legacy on the grounds that it would “endanger national security.”

Students wave copies of Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book at the start of the Cultural Revolution, Beijing, 1966.

Students wave copies of Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book at the start of the Cultural Revolution, Beijing, 1966.  A reconstructed traditional shopping street in Beijing, 2008.

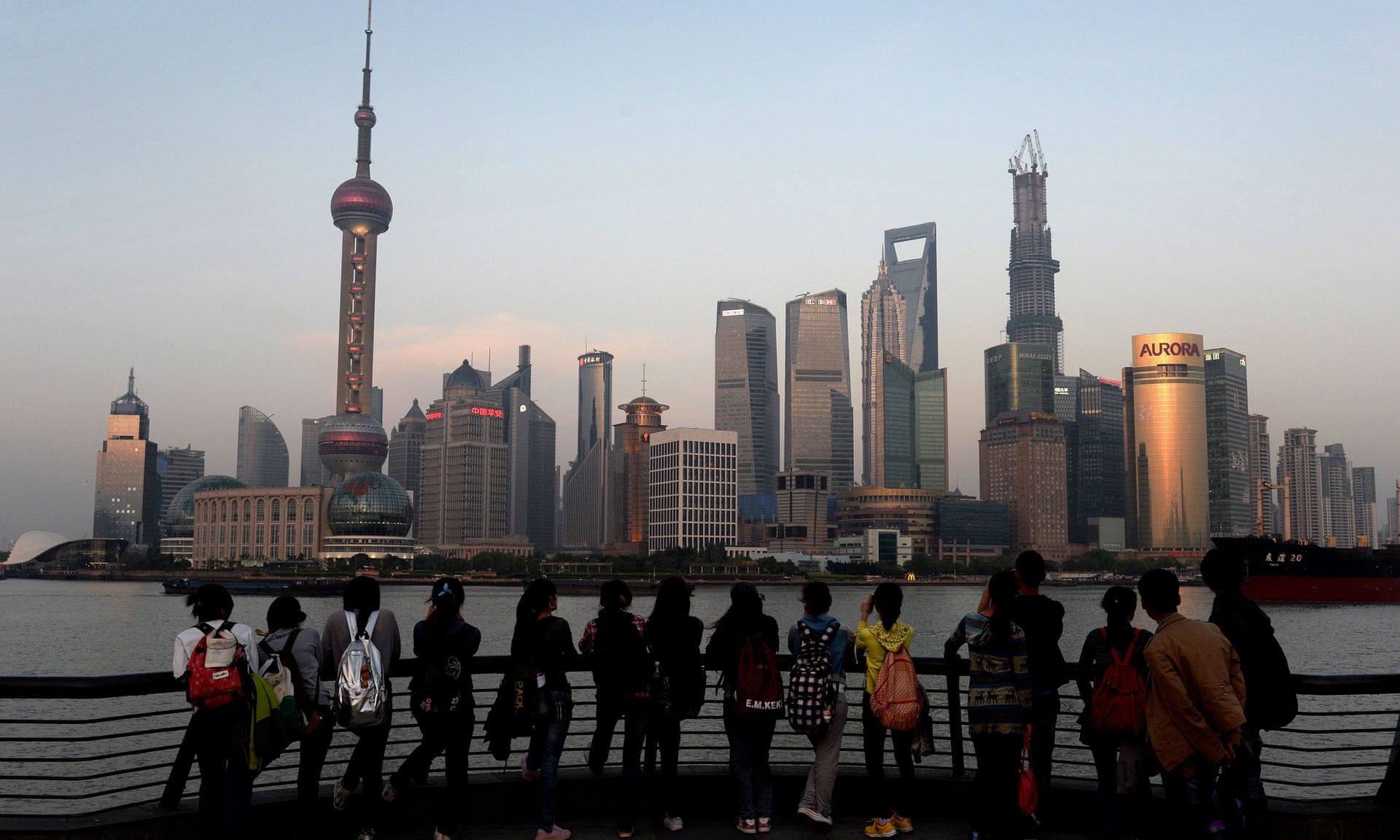

A reconstructed traditional shopping street in Beijing, 2008.  Shanghai’s Pudong financial district, 2013.

Shanghai’s Pudong financial district, 2013.