By JONAH M. KESSEL

During the eight years I lived in China, people would often say they felt as if they had no voice under Communist Party rule.

This was especially true for minorities.

So when Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan herder turned shopkeeper, showed up at my apartment in Beijing in the spring of 2015, I of course wanted to listen to his story.

He told me the Chinese authorities on the Tibetan Plateau had been slowly eradicating the Tibetan language from schools and the business world.

So when Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan herder turned shopkeeper, showed up at my apartment in Beijing in the spring of 2015, I of course wanted to listen to his story.

He told me the Chinese authorities on the Tibetan Plateau had been slowly eradicating the Tibetan language from schools and the business world.

Mr. Tashi believed prohibiting the study of the Tibetan language went against China’s constitution.

The New York Times was not Mr. Tashi’s first stop in his attempt to raise this issue, I learned.

The New York Times was not Mr. Tashi’s first stop in his attempt to raise this issue, I learned.

Chinese state-controlled media had refused to listen to him.

And years earlier, the Chinese authorities had briefly jailed him for expressing his opinions on social media.

Foreign media were his last resort to be heard.

Last week, more than two years after our first meeting, Mr. Tashi was tried in court for “inciting separatism,” a criminal charge that largely amounts to seeking independence from the Chinese state. No verdict has come down yet, but the sentence could hold a punishment of 15 years in prison. (For those hoping for an acquittal, it’s important to note that China’s courts have a 99 percent conviction rate.)

But the root of his crime was talking to me.

In 2015, after I met Mr. Tashi, I made a nine-minute film for The Times about his efforts to raise the issue of Tibetan education to the central government and Chinese state media.

Last week, more than two years after our first meeting, Mr. Tashi was tried in court for “inciting separatism,” a criminal charge that largely amounts to seeking independence from the Chinese state. No verdict has come down yet, but the sentence could hold a punishment of 15 years in prison. (For those hoping for an acquittal, it’s important to note that China’s courts have a 99 percent conviction rate.)

But the root of his crime was talking to me.

In 2015, after I met Mr. Tashi, I made a nine-minute film for The Times about his efforts to raise the issue of Tibetan education to the central government and Chinese state media.

Last week, that documentary was shown in court as the main evidence that Mr. Tashi was inciting separatism.

The use of my film as evidence against Mr. Tashi gets at the heart of one of the thorniest issues that can plague foreign journalists: How do we justify instances when our work — aimed at giving voice to the voiceless and holding the powerful to account — ends up putting its subjects at risk or in danger?

Protesters gathered outside the Chinese Embassy in London on the first anniversary of Mr. Tashi’s detention.

The use of my film as evidence against Mr. Tashi gets at the heart of one of the thorniest issues that can plague foreign journalists: How do we justify instances when our work — aimed at giving voice to the voiceless and holding the powerful to account — ends up putting its subjects at risk or in danger?

Protesters gathered outside the Chinese Embassy in London on the first anniversary of Mr. Tashi’s detention.

Before I made this documentary, Edward Wong — then The Times’s Beijing bureau chief — and I talked at length with Mr. Tashi about the risks he assumed in speaking with us and appearing on video.

Mr. Tashi thought that people wouldn’t believe his story if they couldn’t see him.

I agreed that it wouldn’t hold the same power.

He believed he was acting within the guidelines of the law.

I believed in giving him the agency the Chinese government and state media had refused him.

He believed his voice must be heard at all costs.

But for Mr. Tashi, speaking out has come at a price.

In early 2016, Mr. Tashi — who specifically told me that he was not advocating Tibetan independence — was kidnapped and held in secret detention, without contact with lawyers and family members for months on end.

But for Mr. Tashi, speaking out has come at a price.

In early 2016, Mr. Tashi — who specifically told me that he was not advocating Tibetan independence — was kidnapped and held in secret detention, without contact with lawyers and family members for months on end.

He was subjected to constant interrogation.

For two years, he has waited in jail, silenced.

But along with his struggles came renewed hope in a story long plagued by news fatigue: The international community began speaking up for Mr. Tashi and his cause.

United Nations officials, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, PEN America and the United States Embassy in Beijing have all publicly criticized the Chinese government over the case.

But along with his struggles came renewed hope in a story long plagued by news fatigue: The international community began speaking up for Mr. Tashi and his cause.

United Nations officials, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, PEN America and the United States Embassy in Beijing have all publicly criticized the Chinese government over the case.

Last March, the European Union and Germany voiced concerns at the United Nations Human Rights Council over Mr. Tashi’s arrest.

His case has been covered by countless publications around the world, and his arrest has transformed him from an ordinary shopkeeper with a fifth-grade education into a cultural icon of both justice and oppression.

Protesters gathered in support of Mr. Tashi outside the Chinese consulate in New York on Monday.

Protesters gathered in support of Mr. Tashi outside the Chinese consulate in New York on Monday.

One of Mr. Tashi’s lawyers told us that community members in Yushu, his hometown, had said that Mr. Tashi had “made a big impact on local Tibetans” and that “people admire him.”

The International Tibet Network awarded him the Tenzin Delek Rinpoche Medal of Courage, recognizing his “courage and dedication to promoting Tibetan human rights and justice for the Tibetan people.”

Meanwhile, some have asked me if I regret making my film.

I’ve fielded a variety of queries on the topic — from Tibetan advocacy groups, journalists, students, press freedom groups and social media.

Some have been critical, saying I shouldn’t have made the documentary.

A former State Department official raised the question of whether I am “complicit in exposing a person vulnerable for his ethnicity.”

I’ve struggled with some of these issues on my own.

I’ve struggled with some of these issues on my own.

I’ve wondered: Is our discussion of Tibetan rights worth more than a decade of one man’s freedom? Has Mr. Tashi’s arrest ultimately furthered his cause?

Protesters from @SFTHQ demanding the release of #TashiWangchuk are outside of the Chinese consulate in New York City

These are important and difficult questions.

Protesters from @SFTHQ demanding the release of #TashiWangchuk are outside of the Chinese consulate in New York City

These are important and difficult questions.

And while I don’t have definite answers, I do know this: Mr. Tashi and his concerns are now being acknowledged throughout the world.

On Monday, protesters gathered outside the Chinese consulate in New York City to demand language rights for all Chinese — as well as the release of Mr. Tashi.

Similar gatherings have happened in London.

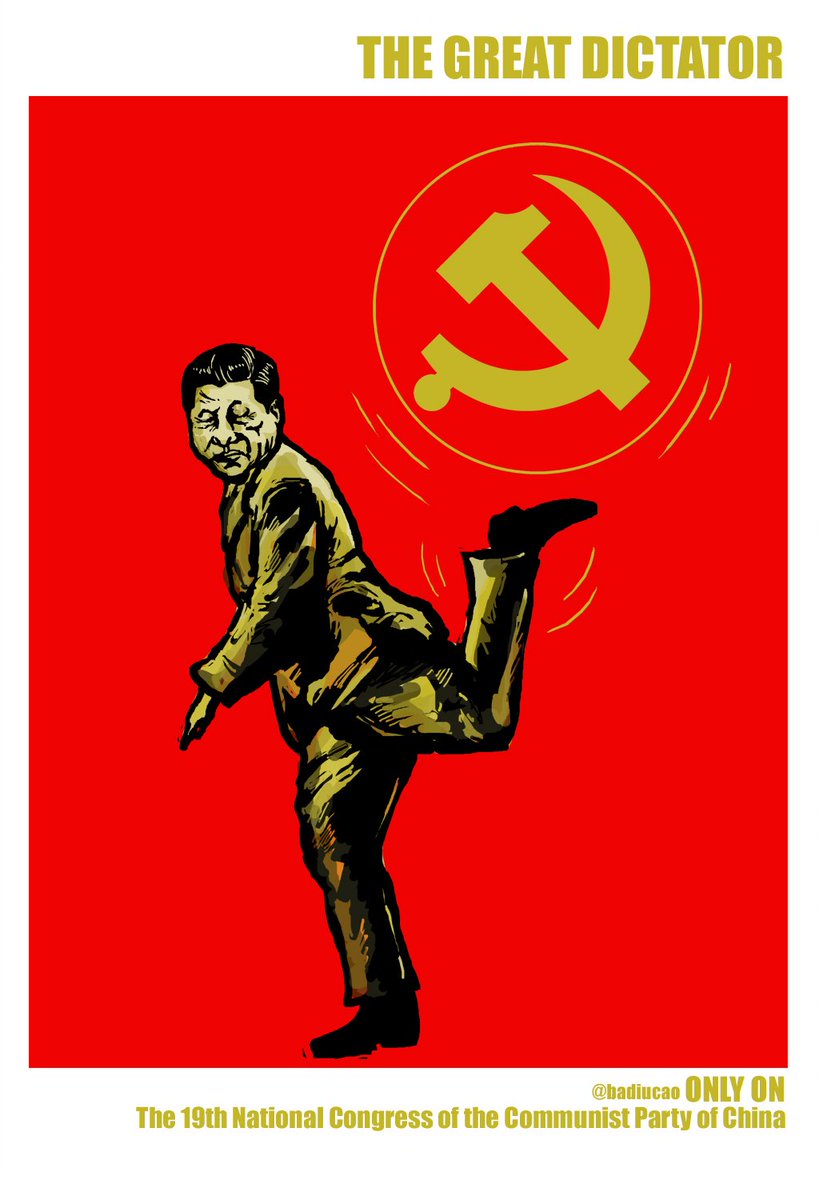

A political cartoonist in Australia has turned his message into pop art.

His voice, at last, is resonating on an international stage.

I know, too, that Mr. Tashi has asked these kinds of questions himself and that he came to his own conclusions: that language rights are human rights, that they are protected by both China’s constitution and international human rights law, and that it was his duty to help protect his culture, no matter the cost.

I know, too, that Mr. Tashi has asked these kinds of questions himself and that he came to his own conclusions: that language rights are human rights, that they are protected by both China’s constitution and international human rights law, and that it was his duty to help protect his culture, no matter the cost.