By Jordan Robertson and Michael Riley

In 2015,

Amazon.com Inc. began quietly evaluating a startup called

Elemental Technologies, a potential acquisition to help with a major expansion of its streaming video service, known today as Amazon Prime Video.

Based in Portland, Ore., Elemental made software for compressing massive video files and formatting them for different devices.

Its technology had helped stream the Olympic Games online, communicate with the International Space Station, and funnel drone footage to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Elemental’s national security contracts weren’t the main reason for the proposed acquisition, but they fit nicely with Amazon’s government businesses, such as the highly secure cloud that Amazon Web Services (AWS) was building for the CIA.

To help with due diligence, AWS, which was overseeing the prospective acquisition, hired a third-party company to scrutinize Elemental’s security, according to one person familiar with the process. The first pass uncovered troubling issues, prompting AWS to take a closer look at Elemental’s main product: the expensive servers that customers installed in their networks to handle the video compression.

These servers were assembled for Elemental by

Super Micro Computer Inc., a San Jose-based company (commonly known as Supermicro) that’s also one of the world’s biggest suppliers of server motherboards, the fiberglass-mounted clusters of chips and capacitors that act as the neurons of data centers large and small.

In late spring of 2015, Elemental’s staff boxed up several servers and sent them to Ontario, Canada, for the third-party security company to test, the person says.

Featured in Bloomberg

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek

, Oct. 8, 2018.

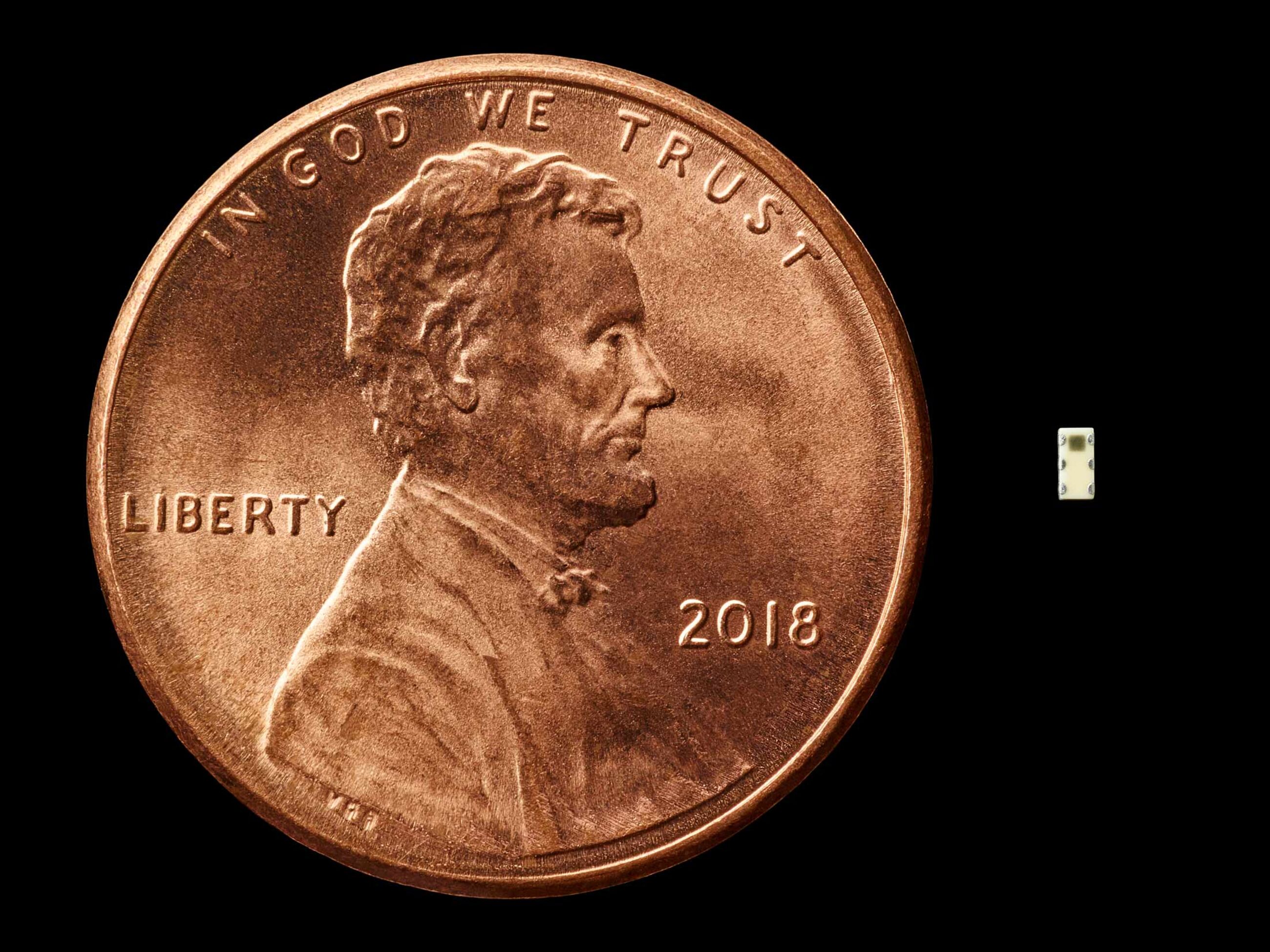

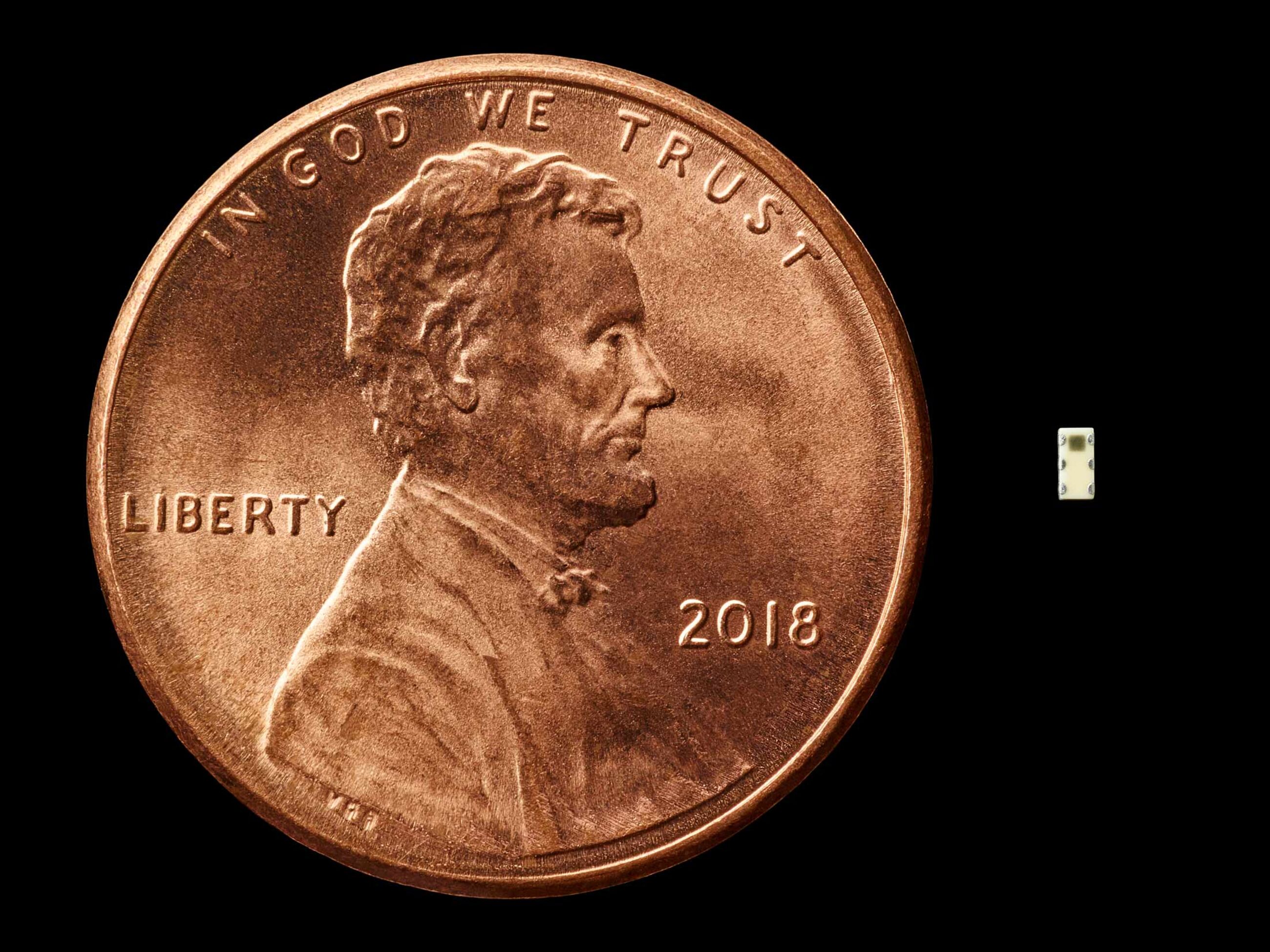

Nested on the servers’ motherboards, the testers found a tiny microchip, not much bigger than a grain of rice, that wasn’t part of the boards’ original design.

Amazon reported the discovery to U.S. authorities, sending a shudder through the intelligence community.

Elemental’s servers could be found in Department of Defense data centers, the CIA’s drone operations, and the onboard networks of Navy warships.

And Elemental was just one of hundreds of Supermicro customers.

During the ensuing top-secret probe, which remains open more than three years later, investigators determined that the chips allowed the attackers to create a stealth doorway into any network that included the altered machines.

Investigators found that the chips had been inserted at factories run by manufacturing subcontractors in China.

This attack was something graver than the software-based incidents the world has grown accustomed to seeing.

Hardware hacks are more difficult to pull off and potentially more devastating, promising the kind of long-term, stealth access that spy agencies are willing to invest millions of dollars and many years to get.

“Having a well-done, nation-state-level hardware implant surface would be like witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow”

There are two ways for spies to alter the guts of computer equipment.

One, known as interdiction, consists of manipulating devices as they’re in transit from manufacturer to customer.

This approach is favored by U.S. spy agencies, according to documents leaked by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden.

The other method involves seeding changes from the very beginning.

One country in particular has an advantage executing this kind of attack: China, which by some estimates makes 75 percent of the world’s mobile phones and 90 percent of its PCs.

Still, to actually accomplish a seeding attack would mean developing a deep understanding of a product’s design, manipulating components at the factory, and ensuring that the doctored devices made it through the global logistics chain to the desired location—a feat akin to throwing a stick in the Yangtze River upstream from Shanghai and ensuring that it washes ashore in Seattle.

“Having a well-done, nation-state-level hardware implant surface would be like witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow,” says

Joe Grand, a hardware hacker and the founder of

Grand Idea Studio Inc.

“Hardware is just so far off the radar, it’s almost treated like black magic.”

But that’s just what U.S. investigators found: The chips had been inserted during the manufacturing process by operatives from a unit of the People’s Liberation Army.

In Supermicro, China’s spies have found a perfect conduit for the most significant supply chain attack known to have been carried out against American companies.Investigators found that

it eventually affected almost 30 companies, including a major bank, government contractors, and the world’s most valuable company, Apple Inc.

Apple was an important Supermicro customer and had planned to order more than 30,000 of its servers in two years for a new global network of data centers.

Three senior insiders at Apple say that in the summer of 2015, it, too, found malicious chips on Supermicro motherboards.

Apple severed ties with Supermicro the following year, for what it described as unrelated reasons.

“We remain unaware of any investigation,” wrote a spokesman for Supermicro, Perry Hayes.

The Chinese government didn’t directly address questions about manipulation of Supermicro servers, issuing a statement that read, in part, “Supply chain safety in cyberspace is an issue of common concern, and China is also a victim.”

The FBI and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, representing the CIA and NSA, declined to comment.

The companies’ denials are countered by six current and former senior national security officials, who—in conversations that began during the Obama administration and continued under the Trump administration—detailed the discovery of the chips and the government’s investigation.

One of those officials and two people inside AWS provided extensive information on how the attack played out at Elemental and Amazon; the official and one of the insiders also described Amazon’s cooperation with the government investigation.

In addition to the three Apple insiders, four of the six U.S. officials confirmed that Apple was a victim.

In all, 17 people confirmed the manipulation of Supermicro’s hardware and other elements of the attacks.

The sources were granted anonymity because of the sensitive, and in some cases classified, nature of the information.

China’s goal was long-term access to high-value corporate secrets and sensitive government networks.

No consumer data is known to have been stolen.

The ramifications of the attack continue to play out.

The Trump administration has made computer and networking hardware, including motherboards, a focus of its latest round of trade sanctions against China, and White House officials have made it clear they think companies will begin shifting their supply chains to other countries as a result.

Such a shift might assuage officials who have been warning for years about the security of the supply chain—even though they’ve never disclosed a major reason for their concerns.

Back in 2006, three engineers in Oregon had a clever idea.

Demand for mobile video was about to explode, and they predicted that broadcasters would be desperate to transform programs designed to fit TV screens into the various formats needed for viewing on smartphones, laptops, and other devices.

To meet the anticipated demand, the engineers started Elemental Technologies, assembling what one former adviser to the company calls a genius team to write code that would adapt the superfast graphics chips being produced for high-end video-gaming machines.

The resulting software dramatically reduced the time it took to process large video files.

Elemental then loaded the software onto custom-built servers emblazoned with its leprechaun-green logos.

Elemental servers sold for as much as $100,000 each, at profit margins of as high as 70 percent, according to a former adviser to the company.

Two of Elemental’s biggest early clients were the Mormon church, which used the technology to beam sermons to congregations around the world, and the adult film industry, which did not.

Elemental also started working with American spy agencies.

In 2009 the company announced a development partnership with In-Q-Tel Inc., the CIA’s investment arm, a deal that paved the way for Elemental servers to be used in national security missions across the U.S. government.

Public documents, including the company’s own promotional materials, show that the servers have been used inside Department of Defense data centers to process drone and surveillance-camera footage, on Navy warships to transmit feeds of airborne missions, and inside government buildings to enable secure videoconferencing.

NASA, both houses of Congress, and the Department of Homeland Security have also been customers.

This portfolio made Elemental a target for Chinese spies.

Supermicro had been an obvious choice to build Elemental’s servers.

Headquartered north of San Jose’s airport, up a smoggy stretch of Interstate 880, the company was founded by Charles Liang, a Taiwanese engineer who attended graduate school in Texas and then moved west to start Supermicro with his wife in 1993.

Silicon Valley was then embracing outsourcing, forging a pathway from Taiwanese, and later Chinese, factories to American consumers, and Liang added a comforting advantage: Supermicro’s motherboards would be engineered mostly in San Jose, close to the company’s biggest clients, even if the products were manufactured overseas.

Today, Supermicro sells more server motherboards than almost anyone else.

It also dominates the $1 billion market for boards used in special-purpose computers, from MRI machines to weapons systems.

Its motherboards can be found in made-to-order server setups at banks, hedge funds, cloud computing providers, and web-hosting services, among other places.

Supermicro has assembly facilities in California, the Netherlands, and Taiwan, but its motherboards—its core product—are all manufactured by contractors in China.

The company’s pitch to customers hinges on unmatched customization, made possible by hundreds of full-time engineers and a catalog encompassing more than 600 designs.

The majority of its workforce in San Jose is Taiwanese or Chinese, and Mandarin is the preferred language, with hanzi filling the whiteboards, according to six former employees.

Chinese pastries are delivered every week, and many routine calls are done twice, once for English-only workers and again in Mandarin.

The latter are more productive, according to people who’ve been on both.

These overseas ties, especially the widespread use of Mandarin, would have made it easier for China to gain an understanding of Supermicro’s operations and to infiltrate the company. (A U.S. official says the government’s probe is still examining whether Chinese spies were planted inside Supermicro and other American companies to aid the attack.)

With more than 900 customers in 100 countries by 2015, Supermicro offered inroads to a bountiful collection of sensitive targets.

“Think of Supermicro as the Microsoft of the hardware world,” says a former U.S. intelligence official who’s studied Supermicro and its business model.

“Attacking Supermicro motherboards is like attacking Windows. It’s like attacking the whole world.”

The security of the global technology supply chain had been compromised, even if consumers and most companies didn’t know it yet

Well before evidence of the attack surfaced inside the networks of U.S. companies, American intelligence sources were reporting that China’s spies had plans to introduce malicious microchips into the supply chain.

The sources weren’t specific, according to a person familiar with the information they provided, and millions of motherboards are shipped into the U.S. annually.

But in the first half of 2014, a different person briefed on high-level discussions says, intelligence officials went to the White House with something more concrete: China’s military was preparing to insert the chips into Supermicro motherboards bound for U.S. companies.

The specificity of the information was remarkable, but so were the challenges it posed.

Issuing a broad warning to Supermicro’s customers could have crippled the company, a major American hardware maker, and it wasn’t clear from the intelligence whom the operation was targeting or what its ultimate aims were.

Plus, without confirmation that anyone had been attacked, the FBI was limited in how it could respond.

The White House requested periodic updates as information came in, the person familiar with the discussions says.

Apple made its discovery of suspicious chips inside Supermicro servers around May 2015, after detecting odd network activity and firmware problems, according to a person familiar with the timeline.

Two of the senior Apple insiders say the company reported the incident to the FBI but kept details about what it had detected tightly held, even internally.

Government investigators were still chasing clues on their own when Amazon made its discovery and gave them access to sabotaged hardware, according to one U.S. official.

This created an invaluable opportunity for intelligence agencies and the FBI—by then running a full investigation led by its cyber- and counterintelligence teams—to see what the chips looked like and how they worked.

The chips on Elemental servers were designed to be as inconspicuous as possible, according to one person who saw a detailed report prepared for Amazon by its third-party security contractor, as well as a second person who saw digital photos and X-ray images of the chips incorporated into a later report prepared by Amazon’s security team.

Gray or off-white in color, they looked more like signal conditioning couplers, another common motherboard component, than microchips, and so they were unlikely to be detectable without specialized equipment.

Depending on the board model, the chips varied slightly in size, suggesting that the Chinese had supplied different factories with different batches.

Officials familiar with the investigation say the primary role of implants such as these is to open doors that other attackers can go through.

“Hardware attacks are about access,” as one former senior official puts it.

In simplified terms, the implants on Supermicro hardware manipulated the core operating instructions that tell the server what to do as data move across a motherboard.

This happened at a crucial moment, as small bits of the operating system were being stored in the board’s temporary memory en route to the server’s central processor, the CPU.

The implant was placed on the board in a way that allowed it to effectively edit this information queue, injecting its own code or altering the order of the instructions the CPU was meant to follow. Deviously small changes could create disastrous effects.

Since the implants were small, the amount of code they contained was small as well.

But they were capable of doing two very important things: telling the device to communicate with one of several anonymous computers elsewhere on the internet that were loaded with more complex code; and preparing the device’s operating system to accept this new code.

The illicit chips could do all this because they were connected to the baseboard management controller, a kind of superchip that administrators use to remotely log in to problematic servers, giving them access to the most sensitive code even on machines that have crashed or are turned off.

This system could let the attackers alter how the device functioned, line by line, however they wanted, leaving no one the wiser.

To understand the power that would give them, take this hypothetical example: Somewhere in the Linux operating system, which runs in many servers, is code that authorizes a user by verifying a typed password against a stored encrypted one.

An implanted chip can alter part of that code so the server won’t check for a password—and presto! A secure machine is open to any and all users.

A chip can also steal encryption keys for secure communications, block security updates that would neutralize the attack, and open up new pathways to the internet.

Should some anomaly be noticed, it would likely be cast as an unexplained oddity.

“The hardware opens whatever door it wants,” says Joe FitzPatrick, founder of Hardware Security Resources LLC, a company that trains cybersecurity professionals in hardware hacking techniques.

U.S. officials had caught China experimenting with hardware tampering before, but they’d never seen anything of this scale and ambition.

The security of the global technology supply chain had been compromised, even if consumers and most companies didn’t know it yet.

What remained for investigators to learn was how the attackers had so thoroughly infiltrated Supermicro’s production process—and how many doors they’d opened into American targets.

Unlike software-based hacks, hardware manipulation creates a real-world trail.

Components leave a wake of shipping manifests and invoices.

Boards have serial numbers that trace to specific factories.

To track the corrupted chips to their source, U.S. intelligence agencies began following Supermicro’s serpentine supply chain in reverse, a person briefed on evidence gathered during the probe says.

As recently as 2016, according to DigiTimes, a news site specializing in supply chain research, Supermicro had three primary manufacturers constructing its motherboards, two headquartered in Taiwan and one in Shanghai.

When such suppliers are choked with big orders, they sometimes parcel out work to subcontractors. In order to get further down the trail, U.S. spy agencies drew on the prodigious tools at their disposal. They sifted through communications intercepts, tapped informants in Taiwan and China, even tracked key individuals through their phones, according to the person briefed on evidence gathered during the probe.

Eventually, they traced the malicious chips to four subcontracting factories that had been building Supermicro motherboards for at least two years.

As the agents monitored interactions among Chinese officials, motherboard manufacturers, and middlemen, they glimpsed how the seeding process worked.

In some cases, plant managers were approached by people who claimed to represent Supermicro or who held positions suggesting a connection to the government.

The middlemen would request changes to the motherboards’ original designs, initially offering bribes in conjunction with their unusual requests.

If that didn’t work, they threatened factory managers with inspections that could shut down their plants.

Once arrangements were in place, the middlemen would organize delivery of the chips to the factories.

The investigators concluded that this intricate scheme was the work of a People’s Liberation Army unit specializing in hardware attacks.

The existence of this group has never been revealed before, but one official says, “We’ve been tracking these guys for longer than we’d like to admit.”

The unit is believed to focus on high-priority targets, including advanced commercial technology and the computers of rival militaries.

In past attacks, it targeted the designs for high-performance computer chips and computing systems of large U.S. internet providers.

The Supermicro attack was on another order entirely from earlier episodes attributed to the PLA.

It threatened to have reached a dizzying array of end users, with some vital ones in the mix.

Apple, for its part, has used Supermicro hardware in its data centers sporadically for years, but the relationship intensified after 2013, when Apple acquired a startup called Topsy Labs, which created superfast technology for indexing and searching vast troves of internet content.

By 2014, the startup was put to work building small data centers in or near major global cities.

This project, known internally as Ledbelly, was designed to make the search function for Apple’s voice assistant, Siri, faster, according to the three senior Apple insiders.

Documents seen by Businessweek show that in 2014, Apple planned to order more than 6,000 Supermicro servers for installation in 17 locations, including Amsterdam, Chicago, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, New York, San Jose, Singapore, and Tokyo, plus 4,000 servers for its existing North Carolina and Oregon data centers.

Those orders were supposed to double, to 20,000, by 2015.

Ledbelly made Apple an important Supermicro customer at the exact same time the PLA was found to be manipulating the vendor’s hardware.Project delays and early performance problems meant that around

7,000 Supermicro servers were humming in Apple’s network by the time the company’s security team found the added chips. Because Apple didn’t provide government investigators with access to its facilities or the tampered hardware, the extent of the attack there remained outside their view.

Microchips found on altered motherboards in some cases looked like signal conditioning couplers.

Microchips found on altered motherboards in some cases looked like signal conditioning couplers.American investigators eventually figured out who else had been hit.

Since the implanted chips were designed to ping anonymous computers on the internet for further instructions, operatives could hack those computers to identify others who’d been affected.

Although the investigators couldn’t be sure they’d found every victim, a person familiar with the U.S. probe says they ultimately concluded that the number was almost 30 companies.

That left the question of whom to notify and how.

U.S. officials had been warning for years that hardware made by two Chinese telecommunications giants,

Huawei Corp. and ZTE Corp., was subject to Chinese government manipulation.

But a similar public alert regarding a U.S. company was out of the question.

Instead, officials reached out to a small number of important Supermicro customers.

One executive of a large web-hosting company says the message he took away from the exchange was clear: Supermicro’s hardware couldn’t be trusted.

“That’s been the nudge to everyone—get that crap out,” the person says.

Amazon, for its part, began acquisition talks with an Elemental competitor, but according to one person familiar with Amazon’s deliberations, it reversed course in the summer of 2015 after learning that Elemental’s board was nearing a deal with another buyer.

Amazon announced its acquisition of Elemental in September 2015, in a transaction whose value one person familiar with the deal places at $350 million.

Multiple sources say that Amazon intended to move Elemental’s software to AWS’s cloud, whose chips, motherboards, and servers are typically designed in-house and built by factories that Amazon contracts from directly.

A notable exception was AWS’s data centers inside China, which were filled with Supermicro-built servers, according to two people with knowledge of AWS’s operations there.

Mindful of the Elemental findings, Amazon’s security team conducted its own investigation into AWS’s Beijing facilities and found altered motherboards there as well, including more sophisticated designs than they’d previously encountered.

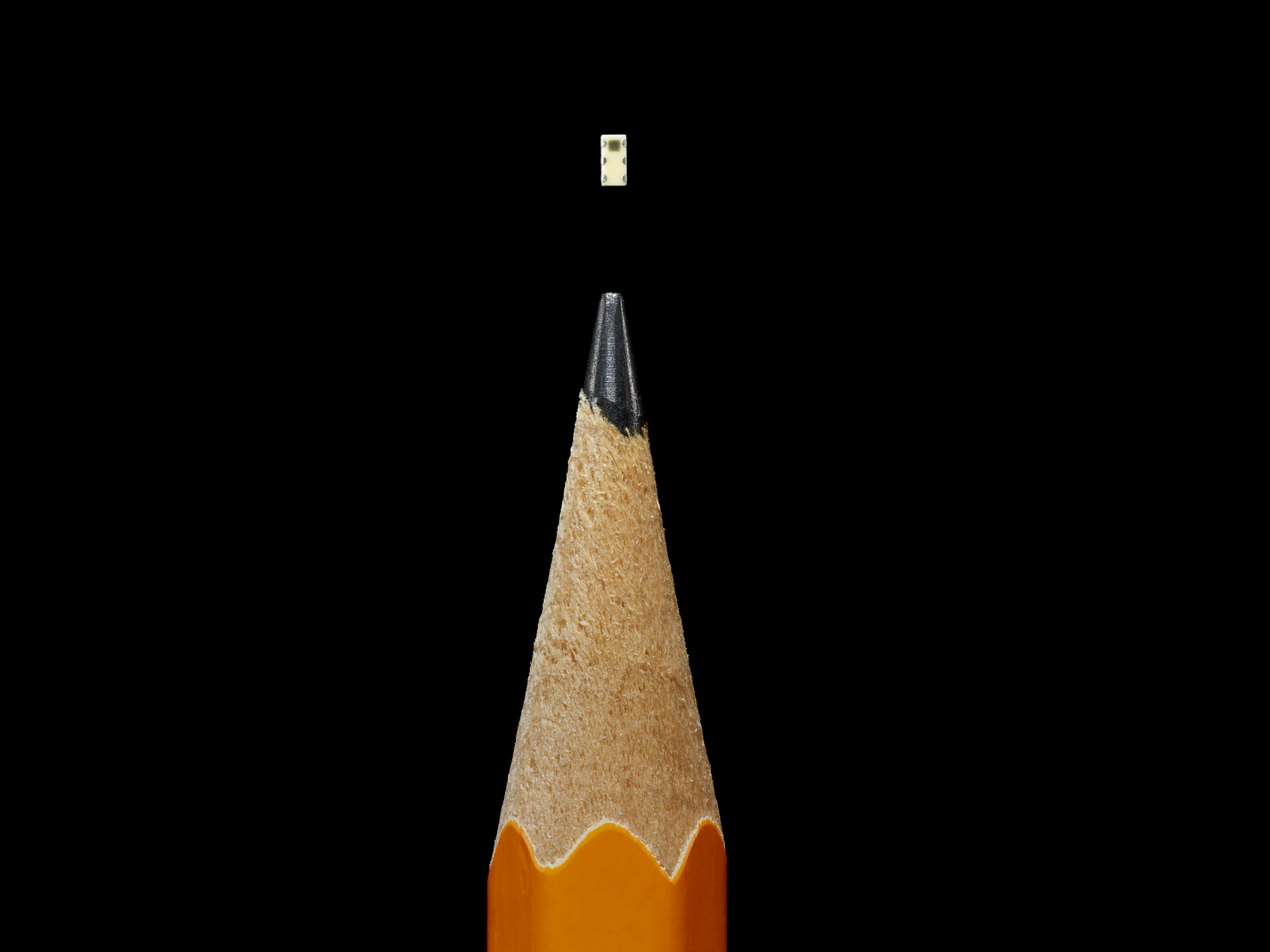

In one case, the malicious chips were thin enough that they’d been embedded between the layers of fiberglass onto which the other components were attached.

That generation of chips was smaller than a sharpened pencil tip, the person says.

China has long been known to monitor banks, manufacturers, and ordinary citizens on its own soil, and the main customers of AWS’s China cloud were domestic companies or foreign entities with operations there.

Still, the fact that the country appeared to be conducting those operations inside Amazon’s cloud presented the company with a Gordian knot.

Its security team determined that it would be difficult to quietly remove the equipment and that, even if they could devise a way, doing so would alert the attackers that the chips had been found, according to a person familiar with the company’s probe.

Instead, the team developed a method of monitoring the chips.

In the ensuing months, they detected brief check-in communications between the attackers and the sabotaged servers but didn’t see any attempts to remove data.

That likely meant either that the attackers were saving the chips for a later operation or that they’d infiltrated other parts of the network before the monitoring began.

Neither possibility was reassuring.

When in 2016 the Chinese government was about to pass a new cybersecurity law—seen by many outside the country as a pretext to give authorities wider access to sensitive data—Amazon decided to act, the person familiar with the company’s probe says.

The person familiar with Amazon’s probe casts the sale as a choice to “hack off the diseased limb.”

As for Apple, one of the three senior insiders says that in the summer of 2015, a few weeks after it identified the malicious chips, the company started removing all Supermicro servers from its data centers, a process Apple referred to internally as “going to zero.”

Every Supermicro server, all 7,000 or so, was replaced in a matter of weeks, the senior insider says.

In 2016, Apple informed Supermicro that it was severing their relationship entirely—a decision a spokesman for Apple ascribed in response to

Businessweek’s questions to an

unrelated and relatively minor security incident.

That August, Supermicro’s CEO, Liang, revealed that the company had lost two major customers. Although he didn’t name them, one was later identified in news reports as Apple.

He blamed competition, but his explanation was vague.

“When customers asked for lower price, our people did not respond quickly enough,” he said on a conference call with analysts.

Hayes, the Supermicro spokesman, says the company has never been notified of the existence of malicious chips on its motherboards by either customers or U.S. law enforcement.

Concurrent with the illicit chips’ discovery in 2015 and the unfolding investigation, Supermicro has been plagued by an accounting problem, which the company characterizes as an issue related to the timing of certain revenue recognition.

After missing two deadlines to file quarterly and annual reports required by regulators, Supermicro was

delisted from the Nasdaq on Aug. 23 of this year.

It marked an extraordinary stumble for a company whose annual revenue had risen sharply in the previous four years, from a reported $1.5 billion in 2014 to a projected $3.2 billion this year.

One Friday in late September 2015, President Barack Obama and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping appeared together at the White House for an hourlong press conference headlined by a landmark deal on cybersecurity.

After months of negotiations, the U.S. had extracted from China a grand promise: It would no longer support the theft by hackers of U.S. intellectual property to benefit Chinese companies.

Left out of those pronouncements, according to a person familiar with discussions among senior officials across the U.S. government, was the White House’s deep concern that China was willing to offer this concession because it was already developing far more advanced and surreptitious forms of hacking founded on its near monopoly of the technology supply chain.

In the weeks after the agreement was announced, the U.S. government quietly raised the alarm with several dozen tech executives and investors at a small, invite-only meeting in McLean, Va., organized by the Pentagon.

According to someone who was present, Defense Department officials briefed the technologists on a recent attack and asked them to think about creating commercial products that could detect hardware implants.

Attendees weren’t told the name of the hardware maker involved, but it was clear to at least some in the room that it was Supermicro, the person says.

The problem under discussion wasn’t just technological.

It spoke to decisions made decades ago to send advanced production work to Southeast Asia.

In the intervening years, low-cost Chinese manufacturing had come to underpin the business models of many of America’s largest technology companies.

Early on, Apple, for instance, made many of its most sophisticated electronics domestically.

Then in 1992, it closed a state-of-the-art plant for motherboard and computer assembly in Fremont, Calif., and sent much of that work overseas.

Over the decades, the security of the supply chain became an article of faith despite repeated warnings by Western officials.

A naive belief formed that China was unlikely to jeopardize its position as workshop to the world by letting its spies meddle in its factories.

That left the decision about where to build commercial systems resting largely on where capacity was greatest and cheapest.

“You end up with a classic Satan’s bargain,” one former U.S. official says.

“You can have less supply than you want and guarantee it’s secure, or you can have the supply you need, but there will be risk. Every organization has accepted the second proposition.”

In the three years since the briefing in McLean, no commercially viable way to detect attacks like the one on Supermicro’s motherboards has emerged—or has looked likely to emerge.

Few companies have the resources of Apple and Amazon, and it took some luck even for them to spot the problem.

“This stuff is at the cutting edge of the cutting edge, and there is no easy technological solution,” one of the people present in McLean says.

“You have to invest in things that the world wants. You cannot invest in things that the world is not ready to accept yet.”