Hong Kong democracy protester was ambushed by masked Chinese in Australia

By Ben Smee and Ben Doherty

The allegations made by Jack* match a trend of Chinese noisy intimidation and surveillance on Australian soil.

A “frontline” Hong Kong democracy protester who recently fled the territory in fear of his safety says he was ambushed and chased in an Australian city by a group of masked Chinese men.

“They were nearby my house and waiting for me,” Jack* told Guardian Australia.

“They knew my address, they knew where I was going to be.

“I think they don’t want to hurt me, they just want to make me scared. It was like intimidation, a message that ‘we know where you are’.”

Guardian Australia has been able to confirm some elements of Jack’s story, including that he arrived in Australia a few months ago and has attended pro-Hong Kong demonstrations since arriving.

“I think they don’t want to hurt me, they just want to make me scared. It was like intimidation, a message that ‘we know where you are’.”

Guardian Australia has been able to confirm some elements of Jack’s story, including that he arrived in Australia a few months ago and has attended pro-Hong Kong demonstrations since arriving.

He has since reported the incident to police.

Human rights advocates and China experts say the claims match a trend of intimidation and surveillance on Australian soil.

Human rights advocates and China experts say the claims match a trend of intimidation and surveillance on Australian soil.

Several recent incidents – including a brawl at the University of Queensland where pro-China participants were praised by the consulate – have raised concerns about the extraterritorial activities of China, including the state’s pursuit of critics beyond its borders.

Jack told Guardian Australia he expected to be safe in hiding in Australia and that he had no choice but to leave Hong Kong after being arrested twice earlier this year and seemingly targeted by Hong Kong police since.

Jack told Guardian Australia he expected to be safe in hiding in Australia and that he had no choice but to leave Hong Kong after being arrested twice earlier this year and seemingly targeted by Hong Kong police since.

Police also twice searched his parents’ home.

“I love Hong Kong and wish I was in Hong Kong but I felt I had no choice,” Jack said.

“I love Hong Kong and wish I was in Hong Kong but I felt I had no choice,” Jack said.

“They came with a warrant to search my house.”

Jack said he was beaten when he was first arrested and then held in a police station in Hong Kong, in a room with no cameras, for 48 hours before being charged with unlawful assembly.“

My family and the lawyer went to the police station to look for me but the police said that I wasn’t there,” he said.

Jack said he was beaten when he was first arrested and then held in a police station in Hong Kong, in a room with no cameras, for 48 hours before being charged with unlawful assembly.“

My family and the lawyer went to the police station to look for me but the police said that I wasn’t there,” he said.

“It was like torture inside. They kept me awake, they kept checking on me every hour. They splashed water on me. So I was soaked in ... cold water. They turned down the aircon to be a lot colder than normal.”

After several months, Jack said he and other protesters became increasingly concerned for their safety.

After several months, Jack said he and other protesters became increasingly concerned for their safety.

They began to carry around “death notes” with messages to family members.

“I was one of the most frontline protesters,” he said.

“I was one of the most frontline protesters,” he said.

“One of the more radical in a way. Most of my group members are willing to sacrifice themselves, willing to be injured or arrested, and so they all kept a death note in their pocket.

“Because I was one of the frontline protesters ... I got more scared of the police and what they might do to me.”

Jack has been supported by a network of Hong Kong expats and supporters since arriving in Australia.

“Because I was one of the frontline protesters ... I got more scared of the police and what they might do to me.”

Jack has been supported by a network of Hong Kong expats and supporters since arriving in Australia.

He said he did not expect to be approached by the masked Chinese men, who followed him home after an Australian rally.

“No, it’s not unsafe in Australia,” he said.

“[The Chinese] just want to make you scared.

“I have never seen them again. Maybe they just want to make you scared, don’t say anything bad about China or anything. If I’m scared, I’m not a protester.”

“[The Chinese] just want to make you scared.

“I have never seen them again. Maybe they just want to make you scared, don’t say anything bad about China or anything. If I’m scared, I’m not a protester.”

Elaine Pearson, the Australia director for Human Rights Watch, said allegations of masked assailants assaulting protesters on Australia soil were disturbing.

“This person escaped Hong Kong and yet it seems like the surveillance apparatus of the Chinese state is alive and well right here in Australia,” she said.

“This person escaped Hong Kong and yet it seems like the surveillance apparatus of the Chinese state is alive and well right here in Australia,” she said.

“Up until now, we’ve seen intimidation, harassment and surveillance of students and activists protesting on university campuses but brazen acts of physical violence are a real step up.

“The new foreign interference laws are supposed to protect people from such acts and send a message to foreign governments and their proxies not to interfere. But these allegations call into question whether that message is getting through. Police should thoroughly investigate these allegations and hold the perpetrators to account.”

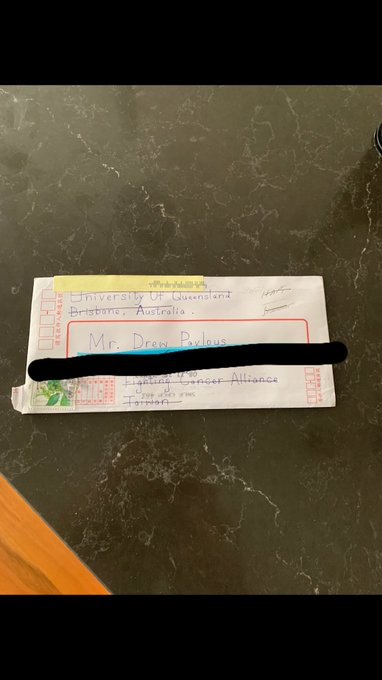

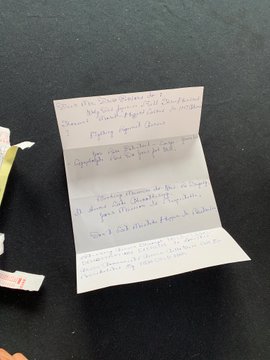

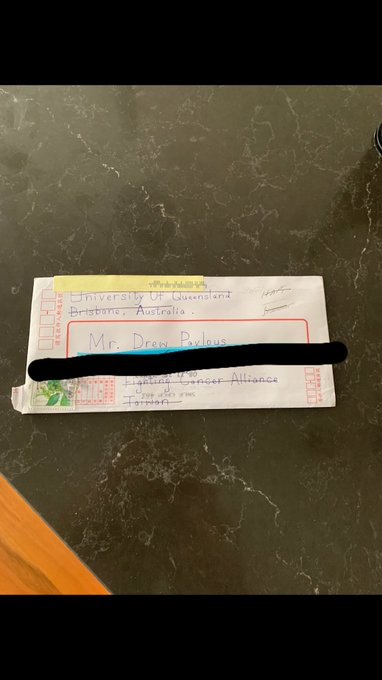

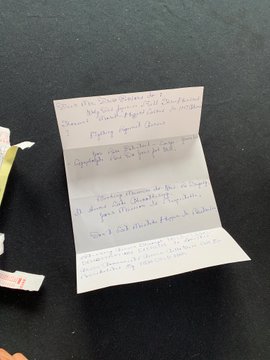

Drew Pavlou, a University of Queensland student who is taking legal action against the Chinese consul general in Brisbane, Xu Jie, said that last week he began receiving threats at his home address.

Drew Pavlou@DrewPavlou

Really terrified -- my family and I have been receiving death threats for months due to my pro Hong Kong activism in Brisbane Australia . But this is a new escalation -- received this threatening letter in mail today, meaning the address of my family home has been compromised.

531

8:10 AM - Nov 21, 2019

“To me, it seems like it must be some sort of coordinated approach,” Pavlou said.

“The new foreign interference laws are supposed to protect people from such acts and send a message to foreign governments and their proxies not to interfere. But these allegations call into question whether that message is getting through. Police should thoroughly investigate these allegations and hold the perpetrators to account.”

Drew Pavlou, a University of Queensland student who is taking legal action against the Chinese consul general in Brisbane, Xu Jie, said that last week he began receiving threats at his home address.

Drew Pavlou@DrewPavlou

Really terrified -- my family and I have been receiving death threats for months due to my pro Hong Kong activism in Brisbane Australia . But this is a new escalation -- received this threatening letter in mail today, meaning the address of my family home has been compromised.

531

8:10 AM - Nov 21, 2019

“To me, it seems like it must be some sort of coordinated approach,” Pavlou said.

“I had a letter sent to my house, it was a clear message that they know my address. It’s not just heat of the moment, two opposing sides clashing at a protest, it’s planned.”

Death threats in Melbourne

The artist Badiucao, who has been an outspoken critic of Beijing through his artwork and his ABC documentary China’s Artful Dissident, said Beijing’s “sharp power” was manipulating members of the Chinese community in Australia.

“No one who has a different voice against Beijing feels safe in Australia,” he said.

“Like the Hong Kong [protester], I certainly do not feel safe either. I have experienced being followed by Chinese men several times and a possible home invasion.

“Death threats have been sent to me on a daily basis via social media and the people behind those trolls are not just movement-hired bots but real Chinese students living and studying in Melbourne, the city I see as home now. But I am not scared of those threats, I just feel sorry for those Chinese kids being brainwashed and missing the chance to see the truth of China, Hong Kong and the world.”

*Jack’s name has been changed

“Death threats have been sent to me on a daily basis via social media and the people behind those trolls are not just movement-hired bots but real Chinese students living and studying in Melbourne, the city I see as home now. But I am not scared of those threats, I just feel sorry for those Chinese kids being brainwashed and missing the chance to see the truth of China, Hong Kong and the world.”

*Jack’s name has been changed

The Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigners Joshua Wong (far left) and Denise Ho (left) testify in Congress.

The Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigners Joshua Wong (far left) and Denise Ho (left) testify in Congress.

This picture taken on June 22, 2019 shows a man taking photographs of artwork and messages in support of protesters opposed to a China extradition law posted on the ‘Lennon Wall’ outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong.

This picture taken on June 22, 2019 shows a man taking photographs of artwork and messages in support of protesters opposed to a China extradition law posted on the ‘Lennon Wall’ outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong.  This picture taken on September 10, 2019 shows mooncakes, adorned with a popular slogan from recent pro-democracy protests, being prepared for the annual mid-autumn festival at a bakery in Hong Kong.

This picture taken on September 10, 2019 shows mooncakes, adorned with a popular slogan from recent pro-democracy protests, being prepared for the annual mid-autumn festival at a bakery in Hong Kong.