In East Turkestan the authorities have separated nearly half a million children from their families, aiming to instill loyalty to China and the Communist Party.

By Amy Qin

HOTAN, China — The first grader was a good student and beloved by her classmates, but she was inconsolable, and it was no mystery to her teacher why.

“The most heartbreaking thing is that the girl is often slumped over on the table alone and crying,” he wrote on his blog.

“When I asked around, I learned that it was because she missed her mother.”

The mother, he noted, had been sent to a detention camp for Muslim ethnic minorities.

The girl’s father had passed away, he added.

But instead of letting other relatives raise her, the authorities put her in a state-run boarding school — one of hundreds of such facilities that have opened in China’s far western East Turkestan colony.

As many as a million ethnic Uighurs, Kazakhs and others have been sent to concentration camps and prisons in over the past three years, an indiscriminate clampdown aimed at weakening the population’s devotion to Islam.

Even as these mass detentions have provoked global outrage, though, the Chinese government is pressing ahead with a parallel effort targeting the region’s children.

Nearly a half million children have been separated from their families and placed in boarding schools so far, according to a planning document published on a government website, and the ruling Communist Party has set a goal of operating one to two such schools in each of ’s 800-plus townships by the end of next year.

The party has presented the schools as a way to fight poverty, arguing that they make it easier for children to attend classes if their parents live or work in remote areas or are unable to care for them. And it is true that many rural families are eager to send their children to these schools, especially when they are older.

But the schools are also designed to assimilate and indoctrinate children at an early age, away from the influence of their families, according to the planning document, published in 2017.

Students are often forced to enroll because the authorities have detained their parents and other relatives, ordered them to take jobs far from home or judged them unfit guardians.

The schools are off limits to outsiders and tightly guarded, and it is difficult to interview residents in without putting them at risk of arrest.

But a troubling picture of these institutions emerges from interviews with Uighur parents living in exile and a review of documents published online, including procurement records, government notices, state media reports and the blogs of teachers in the schools.

A boarding middle school in Hotan. A government document says such schools immerse children in a Chinese-speaking environment away from the influence of religion.

State media and official documents describe education as a key component of Chinese dictator Xi Jinping’s campaign to wipe out extremist violence in , a ruthless and far-reaching effort that also includes the mass internment camps and sweeping surveillance measures.

The idea is to use the boarding schools as incubators of a new generation of Uighurs who are secular and more loyal to both the party and the nation.

“The long-term strategy is to conquer, to captivate, to win over the young generation from the beginning,” said Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington who has studied Chinese policies that break up Uighur families.

To carry out the assimilation campaign, the authorities in have recruited tens of thousands of teachers from across China, often Han Chinese, the nation’s dominant ethnic group.

At the same time, prominent Uighur educators have been imprisoned and teachers have been warned they will be sent to the camps if they resist.

Thrust into a regimented environment and immersed in an unfamiliar culture, children in the boarding schools are only allowed visits with family once every week or two — a restriction intended to “break the impact of the religious atmosphere on children at home,” in the words of the 2017 policy document.

The campaign echoes past policies in Canada and Australia that took indigenous children from their families and placed them in residential schools to forcibly assimilate them.

“The big difference in China is the scale and how systematic it is,” said Darren Byler, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado who studies Uighur culture and society.

Public discussion in China of the trauma inflicted on Uighur children by separating them from their families is rare.

References on social media are usually quickly censored.

Instead, the state-controlled news media focuses on the party’s goals in the region, where predominantly Muslim minorities make up more than half the population of 25 million.

Visiting a kindergarten near the frontier city of Kashgar this month, Chen Quanguo, the party’s top official in , urged teachers to ensure children learn to “love the party, love the motherland and love the people.”

Abdurahman Tohti, a Uighur living in Istanbul, saw his son in a video shared by a stranger on a Chinese social media platform.

Indoctrinating Children

Abdurahman Tohti left and immigrated to Turkey in 2013, leaving behind cotton farming to sell used cars in Istanbul.

But when his wife and two young children returned to China for a visit a few years ago, they disappeared.

He heard that his wife was sent to prison, like many Uighurs who have traveled abroad and returned to China.

His parents were detained too.

The fate of his children, though, was a mystery.

Then in January, he spotted his 4-year-old son in a video on Chinese social media that had apparently been recorded by a teacher.

The boy seemed to be at a state-run boarding school and was speaking Chinese, a language his family did not use.

Mr. Tohti, 30, said he was excited to see the child, and relieved he was safe — but also gripped by desperation.

“What I fear the most,” he said, “is that the Chinese government is teaching him to hate his parents and Uighur culture.”

Beijing has sought for decades to suppress Uighur resistance to Chinese rule in , in part by using schools in the region to indoctrinate Uighur children.

Until recently, though, the government had allowed most classes to be taught in the Uighur language, partly because of a shortage of Chinese-speaking teachers.

Then, after a surge of antigovernment and anti-Chinese violence, including ethnic riots in 2009 in Urumqi, the regional capital, and deadly attacks by Uighur militants in 2014, Xi ordered the party to take a harder line in , according to internal documents leaked to The New York Times earlier this year.

In December 2016, the party announced that the work of the region’s education bureau was entering a new phase.

Schools were to become an extension of the security drive in , with a new emphasis on the Chinese language, patriotism and loyalty to the party.

In the 2017 policy document, posted on the education ministry’s website, officials from outlined their new priorities and ranked expansion of the boarding schools at the top.

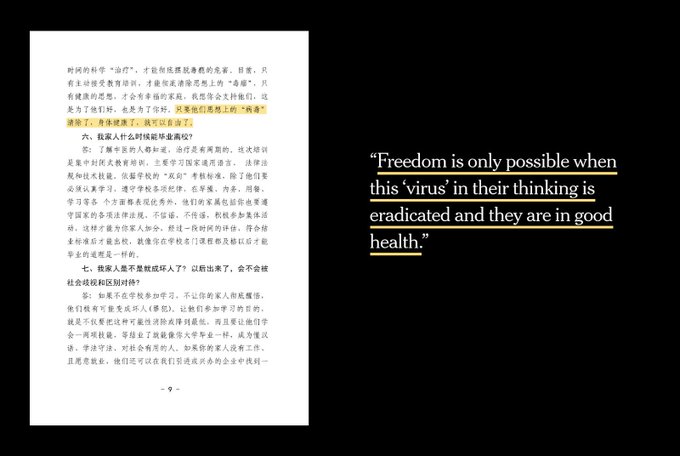

Without specifying Islam by name, the document characterized religion as a pernicious influence on children, and said having students live at school would “reduce the shock of going back and forth between learning science in the classroom and listening to scripture at home.”

By early 2017, the document said, nearly 40 percent of all middle-school and elementary-school age children in — or about 497,800 students — were boarding in schools.

At the time, the government was ramping up efforts to open boarding schools and add dorms to schools, and more recent reports suggest the push is continuing.

Mahmutjan Niyaz, a Uighur businessman living in Istanbul, learned last year that his 5-year-old daughter was sent to a boarding school in after his relatives were detained.

Chinese is also replacing Uighur as the main language of instruction in .

Most elementary and middle school students are now taught in Chinese, up from just 38 percent three years ago.

And thousands of new rural preschools have been built to expose minority children to Chinese at an earlier age, state media reported.

The government argues that teaching Chinese is critical to improving the economic prospects of minority children, and many Uighurs agree.

But the overall campaign amounts to an effort to erase what remains of Uighur culture.

Several Uighurs living abroad said the government had put their children in boarding schools without their consent.

Mahmutjan Niyaz, 33, a Uighur businessman who moved to Istanbul in 2016, said his 5-year-old daughter was sent to one after his brother and sister-in-law, the girl’s guardians, were confined in an internment camp.

Other relatives could have cared for her but the authorities refused to let them.

Now, Mr. Niyaz said, the school has changed the girl.

“Before, my daughter was playful and outgoing,” he said.

“But after she went to the school, she looked very sad in the photos.”

The Kasipi Village Elementary School near Hotan was converted into a full-time boarding school last year, according to an online diary of a Chinese language teacher there.

‘Kindness Students’

In a dusty village near the ancient Silk Road city of Hotan in southern , nestled among fields of barren walnut trees and simple concrete homes, the elementary school stood out.

It was surrounded by a tall brick wall with two layers of barbed wire on top.

Cameras were mounted on every corner.

And at the entrance, a guard wearing a black helmet and a protective vest stood beside a metal detector.

It wasn’t always like this.

Last year, officials converted the school in Kasipi village into a full-time boarding school.

Kang Jide, a Chinese language teacher at the school, described the frenzied process on his public blog on the Chinese social media platform WeChat: In just a few days, all the day students were transferred.

Classrooms were rearranged.

Bunk beds were set up.

Then, 270 new children arrived, leaving the school with 430 boarders, each in the sixth grade or below.

Officials called them “kindness students,” referring to the party’s generosity in making special arrangements for their education.

The government says children in ’s boarding schools are taught better hygiene and etiquette as well as Chinese and science skills that will help them succeed in modern China.

“My heart suddenly melted after seeing the splendid heartfelt smiles on the faces of these left-behind children,” said a retired official visiting a boarding elementary school in Lop County near Hotan, according to a state media report.

He added that the party had given them “an environment to be carefree, study happily, and grow healthy and strong.”

But Kang wrote that being separated from their families took a toll on the children.

Some never received visits from relatives, or remained on campus during the holidays, even after most teachers left.

And his pupils often begged to use his phone to call their parents.

“Sometimes, when they hear the voice on the other end of the call, the children will start crying and they hide in the corner because they don’t want me to see,” he wrote.

“It’s not just the children,” he added.

“The parents on the other end also miss their children of course, so much so that it breaks their hearts and they’re trembling.”

The internment camps, which the government describes as job training centers, have cast a shadow even on students who are not boarders.

Before the conversion of the school, Kang posted a photo of a letter that an 8-year-old girl had written to her father, who had been sent to a camp.

“Daddy, where are you?” the girl wrote in an uneven scrawl.

“Daddy, why don’t you come back?”

“I’m sorry, Daddy,” she continued.

“You must study hard too.”

Students in Hotan playing soccer in a schoolyard with a dormitory in the background

Nevertheless, Kang was generally supportive of the schools.

On his blog, he described teaching Uighur students as an opportunity to “water the flowers of the motherland.”

“Kindness students” receive more attention and resources than day students.

Boarding schools are required to offer psychological counseling, for example, and in Kasipi, the children were given a set of supplies that included textbooks, clothes and a red Young Pioneer scarf.

Learning Chinese was the priority, Kang wrote, though students were also immersed in traditional Chinese culture, including classical poetry, and taught songs praising the party.

On a recent visit to the school, children in red and blue uniforms could be seen playing in a yard beside buildings marked “cafeteria” and “student dormitory.”

At the entrance, school officials refused to answer questions.

Tighter security has become the norm at schools in .

In Hotan alone, more than a million dollars has been allocated in the past three years to buy surveillance and security equipment for schools, including helmets, shields and spiked batons, according to procurement records.

At the entrance to one elementary school, a facial recognition system had been installed.

Mr. Kang recently wrote on his blog that he had moved on to a new job teaching in northern .

Reached by telephone there, he declined to be interviewed.

But before hanging up, he said his students in Kasipi had made rapid progress in learning Chinese.

“Every day I feel very fulfilled,” he said.

A Uighur child doing his Chinese homework at a bus stop. The government says minority children will have better prospects if they are fluent in Chinese, but Uighur activists worry about losing their culture.

‘Engineers of the Human Soul’

To carry out its campaign, the party needed not only new schools but also an army of teachers, an overhaul of the curriculum — and political discipline.

Teachers suspected of dissent were punished, and textbooks were rewritten to weed out material deemed subversive.

“Teachers are the engineers of the human soul,” the education bureau of Urumqi recently wrote in an open letter, deploying a phrase first used by Stalin to describe writers and other cultural workers.

The party launched an intensive effort to recruit teachers for from across China.

Last year, nearly 90,000 were brought in, chosen partly for their political reliability, officials said at a news conference this year.

The influx amounted to about a fifth of ’s teachers last year, according to government data.

The new recruits, often ethnic Han, and the teachers they joined, mostly Uighurs, were both warned to toe the line.

Those who opposed the Chinese-language policy or resisted the new curriculum were labeled “two-faced” and punished.

The deputy secretary-general of the oasis town of Turpan, writing earlier this year, described such teachers as “scum of the Chinese people” and accused them of being “bewitched by extremist religious ideology.”

Teachers were urged to express their loyalty, and the public was urged to keep an eye on them.

A sign outside a kindergarten in Hotan invited parents to report teachers who made “irresponsible remarks” or participated in unauthorized religious worship.

Officials in also spent two years inspecting and revising hundreds of textbooks and other teaching material, according to the 2017 policy document.

Some who helped the party write and edit the old textbooks ended up in prison, including Yalqun Rozi, a prominent scholar and literary critic who helped compile a set of textbooks on Uighur literature that were used for more than a decade.

Mr. Rozi was charged with attempted subversion and sentenced to 15 years in prison last year, according to his son, Kamaltürk Yalqun.

Several other members of the committee that compiled the textbooks were arrested too, he said.

“Instead of welcoming the cultural diversity of Uighurs, China labeled it a malignant tumor,” said Mr. Yalqun, who lives in Philadelphia.

There is evidence that some Uighur children have been sent to boarding schools far from their homes.

Kalbinur Tursun, 36, entrusted five of her children to relatives when she left to give birth in Istanbul but has been unable to contact them for several years.

Last year, she saw her daughter Ayshe, then 6, in a video circulating on Chinese social media.

It had been posted by a user who appeared to be a teacher at a school in Hotan — more than 300 miles away from their home in Kashgar.

“My children are so young, they just need their mother and father,” Ms. Tursun said, expressing concern about how the authorities were raising them.

“I fear they will think that I’m the enemy — that they won’t accept me and will hate me.”

Kalbinur Tursun, right, at her tailor shop in Istanbul this month.

Workers walk by the perimeter fence of a concentration camp in Dabancheng in East Turkestan, China, on Sept. 4, 2018.

Workers walk by the perimeter fence of a concentration camp in Dabancheng in East Turkestan, China, on Sept. 4, 2018.

An ethnic Uighur demonstrator attends a protest against China in front of the Chinese Consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 1.

An ethnic Uighur demonstrator attends a protest against China in front of the Chinese Consulate in Istanbul on Oct. 1.

Before After: Dome removed

Before After: Dome removed