KEVIN AND JULIA Garratt had spent nearly all of their adult lives in China.

A devout Christian couple in their fifties with an entrepreneurial streak, they operated a café called Peter’s Coffee House, a popular destination in the city of Dandong, according to TripAdvisor.

Dandong is a sprawling border town that sits just across the Yalu River from North Korea.

For tourists and expats, the Garratts’ coffee shop—just a short walk from the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge—was a hub of Western conversation and comfort food.

“After time in North Korea a decent cup of coffee was one of those things I was really looking forward to,” one Australian tourist wrote in early 2014.

They lived in six different Chinese cities over the years, raising four children along the way, before settling in Dandong.

The Garratts had a strong social network in the city, so it didn’t seem odd to either of them when they were invited out to dinner by Chinese acquaintances of a friend who wanted advice on how their daughter could apply to college in Canada.

The meal itself, on August 4, 2014, was formal but not unusual.

After dinner, the Garratts got into an elevator that took them from the restaurant down to a lobby.

The Garratts initially thought they’d stumbled into a party of some kind, maybe a wedding.

But then some men grabbed the couple, separated them, and hustled them toward waiting cars. Everything happened fast, and very little made sense.

As the vehicles pulled away, neither Kevin nor Julia had any idea that it was the last they’d see of one another for three months.

It wasn’t until the two arrived at a police facility that they each realized they were in real trouble.

And it wasn’t until much later still that the couple would understand why they had been taken into custody.

After all, before their detainment, they’d never even heard of a Chinese expat living in Canada named

Su Bin.

WHEN THE GARRATTS first arrived in China, in 1984, the country was still transitioning away from collective farms.

Shanghai had only just opened up to foreign investment; the future megacity Shenzhen still had just a few hundred thousand inhabitants.

Over the ensuing three decades, the couple would watch as China hurtled from eighth-largest economy in the world to second-largest, powered, famously, by mass migrations of people into new industrial cities and the erection of a vast manufacturing and export sector.

But especially in the later years of the Garratts’ career as expats, the country’s growth was also propelled by a more invisible force: a truly epic amount of cheating.

China has become one of the world’s most advanced economies overnight through the rampant, state-sponsored theft of intellectual property from other countries.

This extended campaign of commercial espionage has raided every highly developed economy. (British inventor

James Dyson has complained publicly about Chinese theft of designs for his eponymous high-end vacuums.)

But far and away its biggest targets have been the trade and military secrets of the United States.

From US companies, Chinese hackers and spies have purloined everything from details of wind turbines and solar panels to computer chips and even DuPont’s patented formula for the color white.

When American companies have sued Chinese firms for copyright infringement, Chinese hackers have turned around and broken into their law firms’ computer systems to steal details about the plaintiffs’ legal strategy.

Each theft has allowed Chinese companies to bypass untold years of precious time and R&D, effectively dropping them into the marathon of global competition at the 20th mile.

China’s military has gotten a leg up too.

Coordinated campaigns by China’s Ministry of State Security and the People’s Liberation Army have helped steal the design details of countless pieces of American military hardware, from fighter jets to ground vehicles to robots.

In 2012, National Security Agency director Keith Alexander called it the “greatest transfer of wealth in history,” a phrase he has regularly repeated since.

And yet, despite a great deal of restlessness in the ranks of law enforcement and intelligence agencies, the United States was, for years, all but paralyzed in its response to Chinese hacking.

China simply denied any hand in the thefts, professing to take great umbrage at the idea.

American diplomats were skittish about upsetting a sensitive bilateral relationship.

And American companies, in turn, were often inclined to play dumb and look the other way: Even as they were being robbed silly, they didn’t want to jeopardize their access to China’s nearly 1.4 billion consumers.

John Carlin, who served as assistant attorney general for national security during the Obama administration, recalls one meeting with executives from a West Coast company whose intellectual property was being stolen by Chinese hackers.

The executives even projected that, in seven or eight years, the stolen IP would kill their business model; by that point, a Chinese competitor would be able to undercut them completely with a copycat product.

But the company’s general counsel still didn’t want the government to step in and take action.

“We are going to be coming back to you and complaining,” the general counsel said.

“But we’re not there yet.”

Finally, between 2011 and 2013, the US began to reach a breaking point.

Private

cybersecurity firms released a string of damning investigative reports on China’s patterns of economic espionage; the US government started to talk more publicly about bringing charges against the country’s hackers.

But it was far from clear how any government or company might successfully turn back the tide of Chinese incursions.

Obama pressed the issue of cyberthefts in his first meeting with Xi Jinping in 2013, only to be met with more denials.

This is the story of how the US finally achieved some leverage over China to bring a stop to more than a decade of rampant cybertheft, how a Canadian couple became bargaining chips in China’s desperate countermove, and how the game ended happily—only to start up again in recent months with more rancor and new players.

ON MONDAY, MAY 19, 2014, nearly three months before the Garratts were whisked away into the Dandong night, the US Justice Department called a press conference at its headquarters in Washington, DC.

Attorney general

Eric Holder took the podium to announce charges against five hackers for breaking into the systems of several US companies, including U.S. Steel, Westinghouse, and a renewable-energy outfit called SolarWorld.

The FBI had mocked up a bunch of “Wanted” posters, which made it strikingly clear that the hackers all shared an employer: the Chinese army.

Two of the men were even pictured in their crisp dress uniforms.

The press conference marked the first time the US had ever indicted individual foreign agents for cyber intrusions.

It made front-page headlines across the country, instantly bumping the issue of Chinese economic espionage off the back burner of public consciousness.

But the news came with an inevitable caveat: “The move by the Justice Department was almost certainly symbolic,”

The New York Times wrote, “since there is virtually no chance that the Chinese would turn over the five People’s Liberation Army members named in the indictment.”

A few days later, Carlin and a Justice Department prosecutor named

Adam Hickey were flying back from a meeting with the victims of the PLA hackers.

At the Pittsburgh airport, Carlin lamented the obvious: None of the hackers would face a US courtroom anytime soon.

Everyone at the Justice Department knew it would take more than a single “name and shame” campaign to change the calculus of Chinese behavior; the US needed to apply pressure on multiple fronts, perhaps building up to a threat of sanctions.

Now that they’d made their opening gambit, prosecutors needed a next move, preferably one that would actually put someone in handcuffs.

Sitting in the terminal Carlin said, “The next case, we need a body.”

Hickey smiled. “Actually, I’ve got a case I want to talk to you about,” he said.

Kevin and Julia Garratt

Kevin and Julia Garratt

THE FBI REMAINS cagey today about where and how the conspirators first appeared on the agency’s radar.

The bureau will say only that it opened its investigation after seeing emails between them.

Reading between the lines, the case likely began with intercepts from the NSA, passed through the intelligence community from Fort Meade to the FBI.

Eventually, in late summer 2012, a trove of emails between three Chinese agents landed on the desk of supervisory special agent

Justin Vallese, who runs a squad of cyber agents in the FBI’s Los Angeles field office.

“From day one, we knew it was bad,” Vallese says.

“The contents of those emails are pretty explosive.”

One message, which bore an attachment entitled “C-17 Project Reconnaissance Summary,” appeared to suggest a broad outline of the project therein:

a successful, long-term effort by hackers to steal the design secrets of one of America’s most advanced cargo aircraft, the C-17 military transport.

A $202 million-per-unit craft developed by Boeing, the C-17 had been one of the most expensive military planes ever developed by the US Air Force, costing more than $31 billion to create in the 1980s and ’90s.

Since its completion, the C-17 had become a key means of delivering troops, vehicles, and supplies to the front lines of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as delivering humanitarian supplies the world over.

It’s also used to transport the president’s armored limousines around the globe.

American intelligence agencies knew that, for years, the Chinese had been struggling to build their own large cargo plane, a necessary tool for any modern military that wants to project its power over a large area.

Now Beijing was evidently making some headway—by

raiding Boeing’s trade secrets to build what was essentially a Chinese version of the C-17.

Right away, the FBI alerted Boeing to the intrusions. (Boeing declined to comment on this story.) After that, agents in Los Angeles began wading through encrypted attachments and translating each message from Chinese.

The emails would ultimately give them an incredibly detailed picture of the inner workings of a Chinese espionage operation.

Not only that, they realized, it might also give them a chance to actually arrest someone.

Two of the conspirators—the ones who did the actual hacking—were out of reach in China.

But the third was a successful businessman named

Su Bin, and he was based right here in North America, just a three-hour flight from the agents’ offices in LA.

Su, who in the West went by Stephen, owned an 80-employee Chinese aviation-technology firm called

Lode-Tech and, according to

The Globe and Mail, had a comfortable $2 million house in Richmond, British Columbia.

He had two kids, both born in Canada; his wife had been a gynecologist, and his oldest son went to college in Switzerland.

In 2012, he was interviewed by

The Wall Street Journal as part of a story about wealthy Chinese decamping for the West.

He said

he was the son of an army officer and that he had made millions as an aerospace entrepreneur.

He told the

Journal that he found the rules of the West less restrictive.

“Regulations [in China] mean that businessmen have to do a lot of illegal things,” Su said at the time.

From what the agents could reconstruct,

the hacking conspiracy had begun as early as 2009.

Su’s contributions as a spy, the agents realized, were intimately tied to his work as an entrepreneur.

“Su Bin was what we’d call in the traditional espionage world a spotter—someone who would tee up targets for a nation-state,” explains

Luke Dembosky, one of the prosecutors overseeing the case.

Through Lode-Tech, Su had a deep network of industry contacts, and his team’s espionage began with mining his knowledge of the field:

He would direct his hacker colleagues toward particularly interesting engineers and corporate personnel in the aerospace industry.

Then the hackers likely used basic techniques—standard phishing emails—to attempt to penetrate company executives’ email accounts and, from there, access restricted corporate networks.

According to court records,

once the hackers got inside a network—through “painstaking labor and slow groping,” as they put it—they went back to Su Bin.

They would send him lists of the files they’d uncovered; he would then highlight in yellow the most valuable documents that they should exfiltrate, guiding them through what they were uncovering. (Investigators came to enjoy the secret irony in Lode-Tech’s tagline, printed in big letters on its website: “We will track the world’s aviation advanced technology.”)

It was tedious work.

Some of the file directories ran to thousands of pages; in one dump of nearly 1,500 pages, Su meticulously highlighted 142 files that seemed most likely to be useful to his Chinese Army contacts—files with names like C17Hangar Requirements 112399.pdf and Critical Safety Item(CSI) Report_Sep2006.pdf.

In another 6,000-page directory, he picked out the 22 most promising file folders—hitting on one that FBI agents later calculated contained more than 2,000 files related to the C-17.

ALL TOLD, ACCORDING to their own accounting,

Su and his two Chinese partners stole 630,000 files related to the C-17, totaling about 65 GB of data.

“We safely, smoothly accomplished the entrusted mission in one year, making important contributions to our national defense scientific research development and receiving unanimous favorable comments,” the team wrote.

The C-17 wasn’t the hacker’s only target;

they filched information about other aircraft as well. Investigators believe they pillaged 220 MB of data related to the F-22 Raptor, as well as files related to the F-35, including its flight test protocols, which Su carefully translated into Chinese.

The thefts would be critical to helping the Chinese understand—and copy—the world’s most advanced multirole fighter plane, which had cost $11 billion to develop.

The more they dug, the more the agents realized what a uniquely valuable conspirator Su Bin was, perhaps even sui generis as a spy.

He was conversant with the aerospace community, and he spoke English, Chinese, and the technical jargon of aviation in both languages, able to translate the complex world of industrial design schematics, plans, and handbooks.

“I don’t know how many Su Bins there are,” Vallese says.

Su’s hacking effort provided a staggering return on investment for the Chinese government: According to court documents, the operation cost China around $1 million—an absolute pittance compared to the decades of engineering knowledge, military technology, and construction details that Su and his team were able to steal from Boeing and the US Air Force.

The team’s overseers ran such a tight ship that Su griped in an email about the difficulty of getting reimbursed for expenses.

According to court documents,

the hackers covered their tracks by pinballing stolen files through a sophisticated international server network, with machines planted in the US, Singapore, and Korea.

They carefully disguised documents as they stole them, so as to circumvent the internal intrusion alarms at Boeing.

Then they were careful to move their digital contraband through at least three foreign countries, ensuring that at least one had unfriendly relations with the United States, to throw pursuers off China’s scent.

Ultimately, the files would be deposited on machines near Hong Kong and Macau.

There, officials would pick them up and transfer them back to China—in person, further covering all tracks between the United States and China.

But the evidence the FBI had collected left no doubt that the ultimate customer was the Chinese military—and that Su Bin’s partners were members of the military themselves.

While the two hackers in China have not been charged publicly, the US government knows who they are; according to court records, investigators intercepted an email that one of the hackers had received with a copy of his own ID card, which included his photo, name, and date of birth.

Similarly, emails the FBI traced to the other hacker, one with the subject line “boss,” included photos of both men in Chinese military uniforms.

By late spring 2014, around the time Carlin was sitting in the Pittsburgh airport with Hickey, the FBI had assembled everything it needed to make a case against Su Bin; as it happened, the timing coincided with the Justice Department’s newfound desire to charge someone with Chinese espionage. “We were fortunate to get Su into a place where there was an interest and an appetite for an arrest,” Vallese says.

“We had the right subject and had the ability to put hands on him.”

To actually arrest Su, the FBI needed the cooperation of Canadian authorities.

Once again, timing may have worked in the case’s favor.

Around the same time when the FBI was asking for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s help in detaining Su Bin, according to

The Globe and Mail, Canada was responding to a massive attack by state-sponsored Chinese hackers who had penetrated the network of its National Research Council, which leads the country’s research and development efforts.

Given the chance to help break up a Chinese hacking ring, authorities north of the border were perhaps unusually motivated to help.

In any case, they said yes.

By June 2014, the investigative teams knew that Su Bin was planning to leave the country for China—though no one knew for how long.

They decided that now was the time to act.

A few days before his scheduled trip, Canadian authorities pulled Su Bin over and arrested him.

Right away, China knew that one of its most valuable intelligence assets had been caught.

While the “Wanted” posters and Eric Holder’s indictment of five military hackers had certainly made an impression on Beijing, Carlin says that the follow-up case against Su Bin—which actually brought a spy into custody—helped shape the Chinese response even further.

“The Su Bin case, all but unnoticed by the public, had a large impact on Chinese thinking,” says Carlin, who has coauthored with me a new history of the government’s approach to cyberthreats.

“In the space of barely a month, the United States had taken overt steps against two major Chinese economic espionage operations.”

Vallese says the FBI expected it would be an ordeal to get Su Bin back from Canada.

International extraditions, even from close partners and allies, are always complicated.

“We weren’t under any impression this was going to be easy,” Vallese says.

As Su Bin prepared for his initial court appearances, China quickly decided to send a not-so-subtle message to Canada.

To make America’s northern neighbor think twice about allowing the extradition of Su Bin to the United States, it appears the Ministry of State Security had Kevin and Julia Garratt invited to dinner in Dandong.

AFTER THEIR DETENTION, the Garratts found themselves caught in China’s Kafkaesque justice system, interrogated regularly but with nothing to confess.

Their family retained

James Zimmerman, an American lawyer with the firm Perkins Coie, who had spent nearly two decades working in Beijing.

He began to piece together the case against the couple.

The Chinese government, he realized, was leveling charges against Kevin Garratt that were almost a mirror image of the US charges against Su Bin.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry told

The New York Times that the Garratts were being investigated for stealing intelligence “about Chinese military targets and important national defense research projects, and engaging in activities threatening to Chinese national security.”

As if that weren’t menacing enough, on February 19, 2016, China amended the indictment against Kevin to include more serious charges.

The “evidence” against Kevin, though, appeared mainly to be that he had a history of taking fairly unremarkable photographs in public places—going to Tiananmen Square, say, and filming the soldiers marching around and raising the flag, Zimmerman says.

“Getting caught up with China’s politically driven criminal justice system can be a bleak, depressing experience,” Zimmerman says.

“Due process in China is a different animal than in most Western judicial systems. While the investigators are not allowed to torture the suspects, mistreatment is a matter of definition.”

He spent months shuttling back and forth between meetings with the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Commerce, and Canadian embassy officials.

“My goal was to plead to them that this case was not good for China given the dearth of evidence and the potential for a public backlash.”

Later, Kevin Garratt would precisely recall the outline of the cell he shared with as many as 14 prisoners in China: “About 12 paces by five and a half.”

But even if the diplomatic aftermath of Su Bin’s hacking operation was spinning wildly out of control, the operation’s military objective was just coming to fruition.

In November 2014, while Su Bin and the Garratts sat behind bars, the Chinese rolled out their own knockoff military cargo plane at an annual air show in Zhuhai.

At the show, the Xi'an Y-20—codenamed

Kunpeng after a mythical ancient Chinese bird capable of flying long distances—was parked across the tarmac from an American C-17.

Aviation enthusiasts noted how similar the two planes looked, right down to the design of their tail fins.

The Chinese plane had met its American doppelgänger, just feet apart.

TO ANYONE MONITORING the traffic of Chinese cyberthefts, the one-two punch of the PLA indictments and the Su Bin arrest seemed to make a real difference.

“Since mid-2014, we have seen a notable decline in China-based groups’ overall intrusion activity against entities in the US and 25 other countries,” the cybersecurity firm FireEye concluded in one report.

Many inside the government had worried that the Justice Department’s newly aggressive stance would backfire.

But as it turned out, it was the Garratts who suffered the negative repercussions; otherwise the indictments and Su Bin’s arrest seemed to have compelled China to put the brakes on its hacking.

Because the sky hadn’t fallen, the Obama administration felt emboldened to keep pushing harder. China, they figured, saw its economic espionage—like all espionage—via the lens of cost-benefit analysis.

With the indictment and arrest of Su Bin, the Americans felt that they had begun to change one side of that equation—and now it was time for them to up the ante.

Xi Jinping was scheduled to make his first state visit to Washington at the end of September 2015.

In the weeks leading up to the visit, the Obama administration set out to bring the tensions between the two nations to a head.

In August 2015,

The Washington Post ran an article warning that the US government was getting ready to issue sanctions targeting China for its hacking.

In September, Obama addressed a group of business leaders: “We are preparing a number of measures that will indicate to the Chinese that this is not just a matter of us being mildly upset but is something that will put significant strains on the bilateral relationship if not resolved. We are prepared to take some countervailing actions in order to get their attention.”

Other officials, including national security adviser

Susan Rice, pressed the message behind closed doors: China’s behavior had to change.

The warnings, both public and private, got through.

Just days before Xi’s visit, Beijing dispatched a large, high-level delegation to Washington.

“The Chinese saw they had a big potential embarrassment brewing,” Justice Department deputy assistant attorney general

Luke Dembosky recalls.

No one on the Chinese side wanted Xi’s first state visit to become a showdown over cybersecurity. “They had to let the air out of the balloon.”

The conversations, which included Department of Homeland Security secretary

Jeh Johnson and White House cybersecurity coordinator

Michael Daniel, began with a firm message from the Americans: Don’t even bother denying this is your typical behavior. Let’s move past that.

For days, the negotiations were tense and stilted.

But finally, on the night before the delegation was set to return home, the Chinese called the White House for a final set of talks.

“I was all set to go home, and I got a call at 6:30: ‘Can you be at the White House at 8?’ ” Dembosky recalls.

It turned out to be too late to arrange access to the White House, so the groups met at the Omni Shoreham Hotel instead, perched on the edge of Rock Creek Park.

Aides from the White House, the Justice Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and the State Department, among others, talked through the night with the much-larger Chinese delegation. All of them were aware that the Chinese had a deadline to make their 7:30 am flight home.

“It was one of the most constructive dialogs I’ve ever been part of. For a brief moment, the stars were aligned. They were highly motivated to do the right thing,” Dembosky says.

By morning, they’d worked out an agreement for the two presidents to sign later in Washington.

A few days later, on September 25, 2015,

Barack Obama and Xi Jinping met privately.

As Obama recapped the meeting to the press, he said he had “raised once again our very serious concerns about growing cyberthreats to American companies and American citizens. I indicated that it has to stop. The United States government does not engage in cyber-economic espionage for commercial gain.”

Then the president made an announcement in the Rose Garden that many US leaders had

never thought they’d hear: “Today, I can announce that our two countries have reached a common understanding on the way forward. We’ve agreed that neither the US or the Chinese government will conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information for commercial advantage. In addition, we’ll work together, and with other nations, to promote international rules of the road for appropriate conduct in cyberspace.”

THE WORLD’S TWO largest superpowers had broken new ground, but the travails of the Garratts and Su Bin dragged on.

Julia had been released on bail but was ordered to stay in China, and in January 2016 the Chinese government announced it would try Kevin for espionage.

“Chinese authorities also found evidence that implicates Garratt in accepting tasks from Canadian espionage agencies to gather intelligence in China,” the Xinhua news agency reported.

Behind the scenes, though, the Chinese acknowledged that the charges were absurd—and that there was an easy path for the Garratts’ release, says the couple’s lawyer.

As Zimmerman told

The New York Times, “The Chinese made it clear that the Garratt case was designed to pressure Canada to block Su Bin’s extradition to the US.”

STOLEN SECRETS

The C-17 isn't the only product to have its design lifted by hackers.

Over the past decade, Chinese economic espionage has affected thousands of businesses worldwide, from vacuum-makers to paint manufacturers. —Andrea Powell

- Dyson: Since 2011, British inventor James Dyson has been accusing China of hacking the trade secrets of his eponymous fan and vacuum empire.

- DuPont: In 2014, a man in California was convicted of stealing DuPont’s formula for titanium dioxide—a white pigment used in everything from paint to Oreos—on behalf of the Chinese government.

- American Superconductor: This maker of wind turbines lost more than a billion dollars after its Chinese partner company, Sinovel, used a spy to steal source codes for the machines.

- Westinghouse: In 2010, while Westinghouse was building a few power plants in China, a hacker stole specs for how the company designs and routes the pipes running through its generation facilities.

- Military Projects: In addition to helping Chinese hackers steal plans for the C-17, Chinese-Canadian businessman Su Bin was also charged with pilfering specs for the F-22 stealth fighter plane.

But in February 2016, Su Bin himself foiled China’s bargaining position.

He waived extradition, deciding he would go freely to the US to face charges.

His lawyer later told a US court that Su Bin knew that his extradition proceedings might last longer than the time he’d serve in a US prison.

FBI agents flew to Vancouver and prepared to take custody of Su; Vallese and several colleagues waited next to the FBI’s Gulfstream jet as a Canadian police motorcade pulled onto the tarmac.

“Su was in the backseat of the SUV, sandwiched between two Canadian law enforcement officers,” Vallese recalls.

“All of us got chills.”

On the flight back to California, Vallese says the talk among the agents and Su turned to aviation.

He complimented the FBI’s plane.

Making chitchat, one of the agents asked him if he had a favorite jet.

“Not the C-17,” Su deadpanned.

On March 22, 2016, Su Bin pleaded guilty.

His 35-page agreement was perhaps the most detailed firsthand explanation of China’s spying apparatus ever released in public.

“It was the first time we’d had that kind of success—the first time we’d had someone owning their part in an intrusion like this,” Vallese says.

Su Bin declined to speak publicly, though, in court: “I lost my words now,” he said at his sentencing, where a judge handed him 46 months in federal prison and ordered him to pay a $10,000 fine.

With time served, he was released in October 2017.

The case against the Garratts rapidly unraveled in the wake of Su Bin’s decision to waive extradition. Julia was able to leave China in May 2016, and Kevin was released that September, though he had to pay nearly $20,000 in fines and penalties—money that had been partly designated for a North Korean orphanage project and other aid work.

This spring, FBI director

Christopher Wray stated in public what people in cybersecurity circles had been seeing for a while:

China is back to its old tricks.

It is once again infiltrating US computer systems and stealing information at a massive scale.

“There’s no country that’s even close,” Wray told NBC News in March this year.

“We’re talking about big damages,” President Trump recently told Reuters.

“We’re talking about numbers that you haven’t even thought about.”

“There’s been a massive pickup in the last year and a half,” says

Dmitri Alperovitch, cofounder of the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike.

For a variety of reasons, the 2015 truce between China and the United States didn’t hold—in a way, it’s because both countries have ceased to acknowledge it.

President Donald Trump’s trade war against China has largely been couched as a way to punish China for its years of rampant intellectual property theft.

“After years of unsuccessful US-China dialogs, the United States is taking action to confront China,” wrote the US Trade Representative’s office.

Between 2005 and 2014, the main force behind China’s campaign of cybertheft was the People’s Liberation Army.

In turn, after the outing of the five PLA soldiers in 2014, that agency bore most of the embarrassment and blame for China’s weakened hand in negotiations with the US.

Since 2016, for a host of reasons, the army has had its wings clipped politically by Xi Jinping, both through a reorganization and through anticorruption drives that have seen numerous government officials sidelined, imprisoned, and, in at least one case, even sentenced to death.

Into the vacuum left behind by the PLA, the Chinese Ministry of State Security—a powerful agency that combines elements of the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA—has apparently stepped in and become China’s new central office for cybertheft.

“The PLA have stepped back significantly, but the MSS and their affiliated contractors have stepped into that void,” Alperovitch says.

These new hackers with the Ministry of State Security have evidently learned from the PLA’s mistakes.

“They’ve gotten steadily better,” Alperovitch says.

“They’re thinking much harder about how to be more stealthy.”

After all, no Chinese hacker wants to be the next one splashed across an FBI “Wanted” poster.

Adapted from Dawn of the Code War: Inside America’s Battle Against Russia, China, and the Rising Global Cyber Threat, by John P. Carlin, with Garrett M. Graff (PublicAffairs), published October 2018.

Michael Spavor (L) and Michael Kovrig have been put under "compulsory measures"

Michael Spavor (L) and Michael Kovrig have been put under "compulsory measures" Kevin Garratt is reunited with his wife Julia in Vancouver

Kevin Garratt is reunited with his wife Julia in Vancouver Justin Trudeau raised the Garratt case with Chinese officials in August 2016

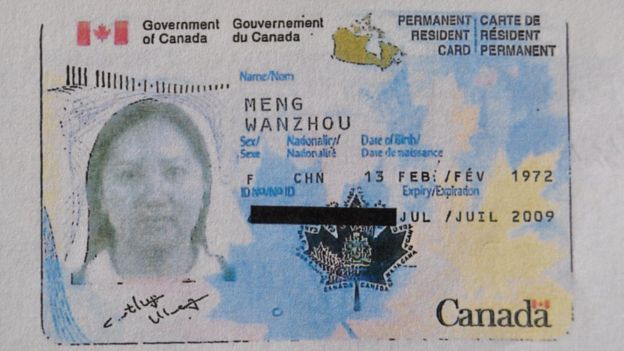

Justin Trudeau raised the Garratt case with Chinese officials in August 2016 Canadians Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig briefly disappeared this month before it was revealed they were taken into custody by Chinese officials. The two men's detention followed the arrest and detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou by Canadian authorities.

Canadians Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig briefly disappeared this month before it was revealed they were taken into custody by Chinese officials. The two men's detention followed the arrest and detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou by Canadian authorities.  Kovrig, an adviser with the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, remains in detention in China.

Kovrig, an adviser with the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, remains in detention in China. Chinese actress Fan Bingbing poses for photographers upon arrival at the opening of the Cannes film festival in southern France in May. One of China's highest paid celebrities, Fan disappeared from public view for four months before apologizing for tax-evasion.

Chinese actress Fan Bingbing poses for photographers upon arrival at the opening of the Cannes film festival in southern France in May. One of China's highest paid celebrities, Fan disappeared from public view for four months before apologizing for tax-evasion.  Former Interpol president Meng Hongwei delivers his opening address at the Interpol World congress in Singapore in July 2017.

Former Interpol president Meng Hongwei delivers his opening address at the Interpol World congress in Singapore in July 2017.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/YWWQOI567BC4NPOGI4LIEZLPFU)