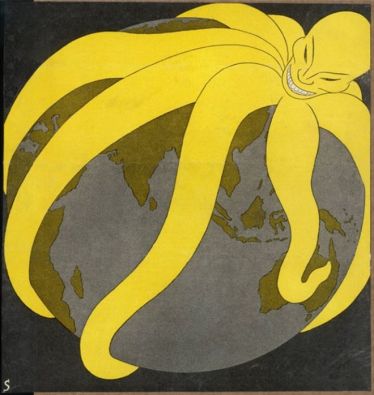

Xi Jinping’s global infrastructure investment programme threatens the west with more than economic dominance. He’s playing a serious political game.

By Tom Miller

Illustration by Thomas Pullin

Earlier this year the first direct freight train from China to the UK arrived at a depot in Barking, east London, carrying containers loaded with consumer goods.

Illustration by Thomas Pullin

Earlier this year the first direct freight train from China to the UK arrived at a depot in Barking, east London, carrying containers loaded with consumer goods.

Named East Wind, it took 16 days to travel 7,500 miles across eight countries, halving the time it would have taken by sea.

A few months later the train made its first return journey, delivering Scotch whisky, pharmaceuticals and baby products to the gargantuan wholesale markets of Yiwu, on China’s east coast.

Last year 1,702 freight trains from China arrived in Europe, double the total in 2015, and more services are being added.

China train rolls into London

The train is named after some famous words of Mao Zedong.

“Either the east wind prevails over the west wind or the west wind prevails over the east wind,” Mao declared in 1957.

Sixty years on, China’s current leaders are doing their best to ensure the east wind prevails.

The trains trundling their way across Eurasia are part of their attempt to build a new Silk Road, inspired by the ancient caravan routes that once crisscrossed the remote desert and steppe of central Asia.

They are motivated today by the quest for economic power and national glory.

By building and financing highways, railways and ports, China’s leaders literally want all roads to lead to Beijing.

The new Silk Road is broader in both geographical and economic scope than its ancient namesake, which was mainly land-based and all about trade and commerce.

The new Silk Road is broader in both geographical and economic scope than its ancient namesake, which was mainly land-based and all about trade and commerce.

On land, it involves building new transport infrastructure and industrial corridors stretching across Central Asia to the Middle East and Europe.

On water, it encompasses new ports and trade routes across the South China Sea into the South Pacific, and through the Indian Ocean all the way to the Mediterranean.

Beijing talks of 65 or so countries belonging to the initiative, but there is no definitive list.

It is diplomatic shorthand describing Chinese financing, investment and construction across much of the developing world.

The initiative is being pushed hard by Xi Jinping, who has spent five years trying to bolster China’s international clout.

The initiative is being pushed hard by Xi Jinping, who has spent five years trying to bolster China’s international clout.

It is central to his “Chinese dream”, unveiled in his first public act as Communist party chief, when he visited the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square.

Emerging from an exhibition that detailed how six decades of Communist rule had brought prosperity to China after a “century of national humiliation”, Xi vowed “to realise the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people”.

Communist-speak for “make China great again”.

Leaders will meet at the 19th party congress next month to determine who will rule China for the next five years and beyond.

Leaders will meet at the 19th party congress next month to determine who will rule China for the next five years and beyond.

Already anointed China’s “core” leader, Xi looks set to tighten his grip on power.

Under his leadership, China has become a more fearful and repressive place – but Xi can claim that his nation is both stronger than it was when he took command.

Emboldened by the weakening position of the United States under Donald Trump, he is using China’s economic brawn to restore its historical position as the region’s dominant power.

The new Silk Road is at the heart of Xi’s nationalistic vision, as Beijing flexes its economic muscles for strategic ends.

The new Silk Road is at the heart of Xi’s nationalistic vision, as Beijing flexes its economic muscles for strategic ends.

By funding and building transport infrastructure, pipelines and power grids, it aims to weave a web of economic dependency and draw other countries ever tighter into its embrace.

China’s interests clearly come first, but few underdeveloped states feel they can ignore its promise to deliver much-needed infrastructure.

The one exception is North Korea, where China’s economic leverage as the hermit kingdom’s biggest trade partner by far appears no match at the moment against Kim Jong-un’s nuclear threat and autarkic ambitions.

East Wind freight carriages arrive in Barking in January.

Key pieces of the new Silk Road, such as the overland freight routes from China to Europe, are already in place.

Direct investment along the road was $30bn in 2015-16, according to Beijing’s records, while Chinese firms signed construction contracts worth $189bn and earned $145bn in 60-odd countries. But there are doubts over its security and commercial feasibility.

Pakistan has reportedly deployed 14,500 security personnel to ensure the safety of some 7,000 Chinese nationals working on the economic corridor.

The danger was evident in May, when two Chinese language teachers were kidnapped and killed by armed men in Quetta, a remote but important section of the corridor.

Freight trains from China to Europe may not prove profitable, however much time they save.

Countries with a history of enmity with China, such as Vietnam and India, fear the strategic implications of China’s expanding tentacles.

New Delhi has condemned China’s port-building in the Indian Ocean, especially in Sri Lanka and Pakistan, as a platform for military expansionism – a “string of pearls” around the neck of Mother India.

This summer’s military standoff with China along the contested border in the Himalayas has only added to India’s concerns.

The threat of conflict between Asia’s giants has overshadowed the ninth annual summit of the five Brics countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – starting in the Chinese port city of Xiamen on Sunday.

The threat of conflict between Asia’s giants has overshadowed the ninth annual summit of the five Brics countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – starting in the Chinese port city of Xiamen on Sunday.

The meeting between Xi and India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, may ease tensions, but the strategic competition will remain.

In other parts of Asia, China’s infrastructure diplomacy is paying dividends in the Philippines – whose president Rodrigo Duterte returned home from Beijing late last year with an investment and trade package worth $24bn after announcing his country’s “separation” from the United States – and Malaysia , whose prime minister Najib Razak declared himself a “true friend” of China after securing deals worth $34bn.

In other parts of Asia, China’s infrastructure diplomacy is paying dividends in the Philippines – whose president Rodrigo Duterte returned home from Beijing late last year with an investment and trade package worth $24bn after announcing his country’s “separation” from the United States – and Malaysia , whose prime minister Najib Razak declared himself a “true friend” of China after securing deals worth $34bn.

And small countries such as Cambodia and Tajikistan are also heavily reliant on China to provide vital public goods.

China’s geopolitical leverage is growing.

China’s geopolitical leverage is growing.

Since the end of the second world war, the US has been the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific – but Trump’s diplomatic missteps are playing into China’s hands.

His decision to bin the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation trade pact that pointedly did not include China, has diminished Washington’s regional clout.

TPP was designed by the Obama administration to anchor the US’s economic and diplomatic presence in Asia at the expense of China.

Instead, Beijing is pushing for an alternative deal that includes China but not the US.

Construction on the Zhuhai-Macau border last week.

As the US under Trump turns inwards, a newly self-confident China is attempting to replace it. Earlier this year, Xi urged delegates at a forum about the new Silk Road in Beijing to reject protectionism and embrace a version of global trade that China’s publicity machine is spinning as “Globalisation 2.0”.

Much of this is bluster, but Xi is playing a serious diplomatic game.

Thirty heads of state attended the forum – not as many as Beijing hoped for, but a sufficient showing for Xi to present himself as an international statesman of substance.

China’s leaders know there is still much diplomatic work to be done, as few countries yet buy its diplomatic mantra about delivering “mutual benefits”.

China’s leaders know there is still much diplomatic work to be done, as few countries yet buy its diplomatic mantra about delivering “mutual benefits”.

Simply put, it is not trusted.

But its hard-headed economic diplomacy is far bolder, more forward-looking and more practical than any of the alternatives.

Under Trump, the US does not have a coherent Asia policy and is no longer viewed as a reliable partner, even by its regional allies.

Japan is still a big source of investment in Asia, but its economy is dwarfed by China’s and it cannot compete as a financier.

From a British perspective, China’s Asian power play looks remote.

From a British perspective, China’s Asian power play looks remote.

If the new Silk Road delivers a few extra containers of cheap consumer goods, so much to the good.

But it matters to us all if China’s economic diplomacy succeeds.

As the outcry this summer over Cambridge University Press’s decision to uphold Beijing’s request to delete 300 politically sensitive articles shows only too clearly, economic leverage buys political power.

Only an international outcry forced Britain’s oldest academic press to backtrack on its decision.

The economic pressure on the west to comply with illiberal demands from Beijing will intensify.

In Asia and beyond, China’s rise will bring many economic opportunities, but it could have politically devastating consequences.

In Asia and beyond, China’s rise will bring many economic opportunities, but it could have politically devastating consequences.

Mao predicted that the east wind would eventually prevail over the west wind.

If he is proved correct, we will all feel its force.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire