China’s Black Week-end

By Ian Johnson

The Last Secret: The Final Documents from the June Fourth Crackdown

edited by Bao Pu

Hong Kong: New Century Press, 362 pp., HK$158.00

Demonstrators and troops during the Tiananmen Square protests, Beijing, June 1989.

When Chinese law professor Xu Zhangrun began publishing articles last year criticizing the government’s turn toward a harsher variety of authoritarianism, it seemed inevitable that he would be swiftly silenced.

Sure enough, Xu was suspended from his teaching duties at Tsinghua University and placed under investigation.

But then, remarkably, dozens of prominent citizens began speaking up.

Some signed a petition, others wrote essays and poems in Xu’s support, and one wrote a song:

And, so this spring

To anyone familiar with Chinese politics, the reference was clear: the anniversary of the June 4, 1989, crackdown on the Tiananmen protests.

The Communist Party’s use of violence to end those peaceful demonstrations left hundreds dead and remains one of the ugliest events in the history of the People’s Republic.

The thirtieth Tiananmen anniversary is complemented by several other important dates, making 2019 the most sensitive year in a generation.

It is also the one hundredth anniversary of the May 4 Movement, a defining moment in Chinese history when traditions were cast aside in favor of a sometimes romantic pursuit of “science” and “democracy.”

And it is the seventieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic as well as the twentieth of the crackdown on one of modern China’s most popular religious movements, Falun Gong, in which scores of people were killed in police custody and thousands sent to labor camps.

Anyone with any political sense knows that this convergence of dates makes 2019 the year to keep quiet.

And yet people continue to speak up.

Why?

For authoritarian regimes like China’s, history is power, because their political systems are legitimized through myths.

In the case of the People’s Republic, the story goes that earlier efforts to modernize China were failures and that only the Chinese Communist Party was able to bullwhip the country into the future. This is the history that every child learns in textbooks, that museums serve up in exhibitions, and that the media push in countless television dramas, news reports, and popular books.

The problem for the dictators is that historical truth is hard to suppress.

The authoritarian state can prevent it from becoming an immediate threat and can eliminate it from the lives of most citizens, but the truth stubbornly endures, inspiring people like Professor Xu and his supporters.

The most recent example of history’s persistence is the publication in Hong Kong of The Last Secret: The Final Documents from the June Fourth Crackdown.

It is the record of a meeting of roughly thirty party elders and senior leaders that took place two weeks after the massacre.

Officially known as the Fourth Plenum of the Thirteenth Party Congress, it was called by China’s top leader, Deng Xiaoping, to force other party leaders to retroactively endorse his decision to use force on the protesters and to fire the Communist Party’s general secretary, Zhao Ziyang, who had opposed using the military to stop the demonstrations.

The officials’ statements of fealty were read out loud and then printed up and distributed at another meeting a few days later for nearly five hundred party officials to “study”—in other words, to internalize as the truthful version of events.

At the end of that meeting, the documents, all stamped “top secret,” were collected in order to maintain their secrecy.

Now, three decades later, one copy has surfaced in Hong Kong and has been published by New Century Press, whose publisher, Bao Pu, has made it his calling to explain the inner workings of the party.

Over the past fourteen years he has published several important works on Chinese politics, including Zhao’s secret memoirs and the diaries of then premier

Li Peng, who stepped in when Zhao refused to endorse force.

2

The book is called

The Last Secret because it was the party’s last word on the events of 1989: a newspeak version of what had happened that all officials, high or low, had to make their own, regardless of what they personally believed or had witnessed.

It is also a “last secret” in that it shows how the party, in the end, is designed to operate: as a one-man dictatorship, which requires obedience achieved by periodic purges and oath-style promises from survivors to follow the boss’s version of reality.

Ultimately, this book is a case study in how the party has managed to keep itself in power, and how the current leadership functions.

That’s not the usual focus of books on Tiananmen.

In a preface to The Last Secret, a writer using the pen name Wu Yulun says that most of our histories of Tiananmen emphasize the dramatic photos and accounts of the freewheeling demonstrations, which for fifty-one days turned the enormous square into an oasis of free speech.

Or they emphasize the details of the massacre: where the troops staged their assault and how many people were killed.

But Wu writes that equally important is what happened in the weeks that followed: As we look back, it is also important to peek through the iron curtain at the powerful forces behind the scenes.

Only then can we hope to understand how the dreams, hopes and lives of millions of people were suddenly changed.

The Last Secret is divided into two parts.

The first is nearly fifty pages of English-language analysis, including Wu’s essay and an introduction by the Columbia University professor

Andrew J. Nathan, who lucidly explains the crucial points of the leaders’ statements.

3

The second part reprints them in full, in Chinese. (The book also includes several previously unpublished photos of events before and after the massacre.)

Tellingly, no one stood up for Zhao.

Even his supporters begged for forgiveness and heaped blame on their former boss.

One, Hu Qili, was a member of the Politburo Standing Committee—the five-person body that with Deng’s blessing ran China’s day-to-day affairs.

Hu acknowledged that he had sided with Zhao in opposing martial law because he worried that bringing troops into a city with large-scale demonstrations would lead to disaster.

Essentially, that was the right call, but Hu couldn’t say that.

Instead, he said:

Now, by studying Comrade [Deng] Xiaoping’s important talk of June 9 and comparing it to my thinking at the time of the events, I deeply realize how inadequate was my comprehension of the truth...

This shows that my political level is low, that my thinking was not clear in the face of great issues of right and wrong affecting the Party’s and the state’s future and fate, and that I did not withstand the test.

Hu never regained the rank he once had, but his self-abasement guaranteed him appointments in the 1990s as a minister and several ceremonial positions, not to mention the generous benefits enjoyed by all retired leaders and their families.

Most of the statements were by hard-liners who—significantly for a meeting that was supposed to emphasize harmony—used the opportunity to vent about the reform process in general.

Former president Li Xiannian, who was about to turn eighty when he delivered his speech, was one of several who opposed Zhao’s efforts to reform state-owned enterprises and promote private business—hallmarks of the early years of reforms and a major reason for China’s economic takeoff. Others, such as the eighty-one-year-old former general Wang Zhen, thought Zhao wasn’t ideologically tough enough and was leading China to convergence with the West.

These and other statements reveal the turmoil that Deng’s reforms unleashed and help explain Zhao’s downfall.

On one hand, Deng wanted Zhao to carry out reforms, but Zhao was also being watched suspiciously by Deng’s more conservative opponents.

On the other hand, Zhao’s downfall shows how uneasy the party is with the social effects of economic reforms—a problem that remains today, as Xi Jinping promotes old-style Communist ideals.

As Nathan puts it:

The more China pursues power and prosperity through technological modernization and engagement with the global economy, the more unwilling are students, intellectuals, and the rising middle class to adhere to a 1950s-style ideological conformity.

The statements show how the party enforces ideological conformity after a crisis.

First, a scapegoat is found—in this case Zhao—and then everyone must acknowledge and bewail their manifold sins, show that they most earnestly repent, and, trusting in the party’s great mercy, throw themselves at the leadership’s feet.

It’s basically an embarrassing exercise in bootlicking, which helps explain why these documents were classified as top secret.

Events like this show that these sorts of purges and groveling sessions are essential in a system with no real rules or internal democracy.

Instead, the decisions of those in charge determine how the party is run.

If the decisions change in some way, then everyone must prove that they will toe the new line.

The documents demonstrate the inherent instability of this crude system of power transfer and control.

When Mao Zedong began to embrace increasingly radical policies starting in the late 1950s, many of his highest-ranking lieutenants suddenly found themselves on the wrong side of his favor and were jettisoned or even killed.

But then those who replaced them—especially his wife Jiang Qing and a small group around her who were dubbed the Gang of Four—were themselves turned into scapegoats, arrested, and jailed after Mao’s death in 1976.

A decade later, when Deng in 1987 lost confidence in the liberal, reforming party secretary Hu Yaobang, the process repeated itself.

Hu had to confess his sins and resign at a major party conference.

Just two years after that it was Zhao’s turn to resign and for leaders to blame him.

A crucial lesson is that the system requires a strong leader.

In the 1980s Deng was one, but he chose to rule indirectly, through intermediaries like Zhao.

This allowed him to discard lieutenants when things went wrong but ultimately hurt the party because it made a mockery of its own processes—Hu and Zhao had done nothing wrong and were not deposed according to any sort of party rules, but simply because Deng faced problems.

It was also part of the reason for the Tiananmen protests, which began shortly after Hu’s death in April 1989.

Many people mourned him precisely because they felt he had been poorly treated by Deng two years earlier.

Senior leaders at the June 1989 meeting understood the problem.

The eighty-one-year-old military and political leader Bo Yibo warned that the party would need to get behind one strong leader—a “core,” or hexin in Chinese—who commanded respect and could take firm control of the government.

“In my view, history will not allow us to go through [a leadership purge] again,” Bo said.

Deng also realized that the system he had created was faulty.

He quickly handed over power to Jiang Zemin and got rid of the informal body of elders who had second-guessed Zhao for much of the 1980s.

But until his death in 1997, Deng still hovered in the background.

Jiang’s successor from 2002 to 2012, Hu Jintao, was likewise relatively weak.

Jiang and Hu each served two terms, which was prematurely declared to be proof that the regime had institutionalized power transfers.

In hindsight, this seems more like an interregnum that occurred because the party lacked a “core”—only Xi was able to assume this mantle after he took power in 2012.

Not surprisingly, two of Xi’s signature policies have been to conduct a purge of top officials (in the guise of an anticorruption campaign) and to abolish term limits.

One of the strange phenomena of modern academia and journalism is that they sometimes fail to publish the obvious.

In this case that would be a readable, accessible, and complete account of the June 4 massacre.

Many worthwhile journalistic accounts appeared shortly after the event,

4 but they are now at least twenty years out of date, and thus weren’t able to take into account the flood of memoirs and secret documents that have come out since then.

These include The Tiananmen Papers (a collection of internal party documents recounting the events), Zhao’s memoirs, Li Peng’s diaries, and works by former Chinese political advisers Wu Wei and Wu Guoguang.

This makes Wu Yulun’s essay in The Last Secret of great value.

It synthesizes much of this new material in trying to answer a basic question, encapsulated in the title of his essay: “How the Party Decided to Shoot Its People.”

Like others, Wu argues that the massacre was the result of a series of mishaps that caused a manageable situation to spiral out of control.

But Wu also makes a strong case that Deng favored some sort of forceful action from the start: this wasn’t an accident but an act of conviction.

When the protests started after Hu’s death, Deng initially yielded to Zhao, whom he had supported and promoted for over a decade.

Zhao realized it would be wrong to crack down on people mourning a former general secretary of the Communist Party, and so he counseled negotiation.

But Deng seems to have lost patience as the protests continued.

He was able to push his less tolerant approach after April 23, when Zhao went to North Korea on a week-long state visit.

Zhao left explicit instructions with Premier Li Peng to follow his moderate course.

According to Li’s diary, which Wu cites to great effect, Li agreed, but he also wrote that another senior leader “encouraged” him to meet Deng.

Whether Li met Deng is unclear, but he seemed to have realized that Deng wanted a harder line.

Li’s diary confirms that on April 24 he convened a meeting of leaders, making sure to exclude one of Zhao’s trusted lieutenants.

The leaders ordered the party’s mouthpiece, People’s Daily, to issue a strongly worded editorial on April 26 condemning the protests as “turmoil.”

Famously, the editorial backfired, and the next day more than 500,000 people surged into the square—as Wu Yulun puts it, this was “an unprecedented event in the history of the People’s Republic of China. For the first time in the Communist Party’s reign, people willfully took action against the wishes of the paramount leader.”

Zhao records in his memoirs that when he returned to Beijing on April 30, Deng refused to see him—clearly he felt that Zhao had been following the wrong course.

On May 2, Hong Kong’s Ming Pao newspaper, then a very reliable source of information on mainland politics, reported that Zhao was on his way out.

What probably prevented Deng from taking immediate action was Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s imminent arrival in Beijing to repair the thirty-year rift between the two Communist giants.

This was Deng’s chance to cement his place in history, so he waited until the meeting with Gorbachev took place, and in the intervening two weeks the protests grew even larger.

The day after Gorbachev left for Shanghai on May 16, Deng convened a meeting that authorized the use of force.

Then it was only a matter of time before troops were deployed.

Reading these essays and documents, one is struck by the fragility of the party’s grip on power.

In 1989 public opinion had soured because of inflation, corruption, and stagnating living standards—and the party itself was divided among reformers and hard-liners.

Ultimately, it was this confluence of events that led to the massacre.

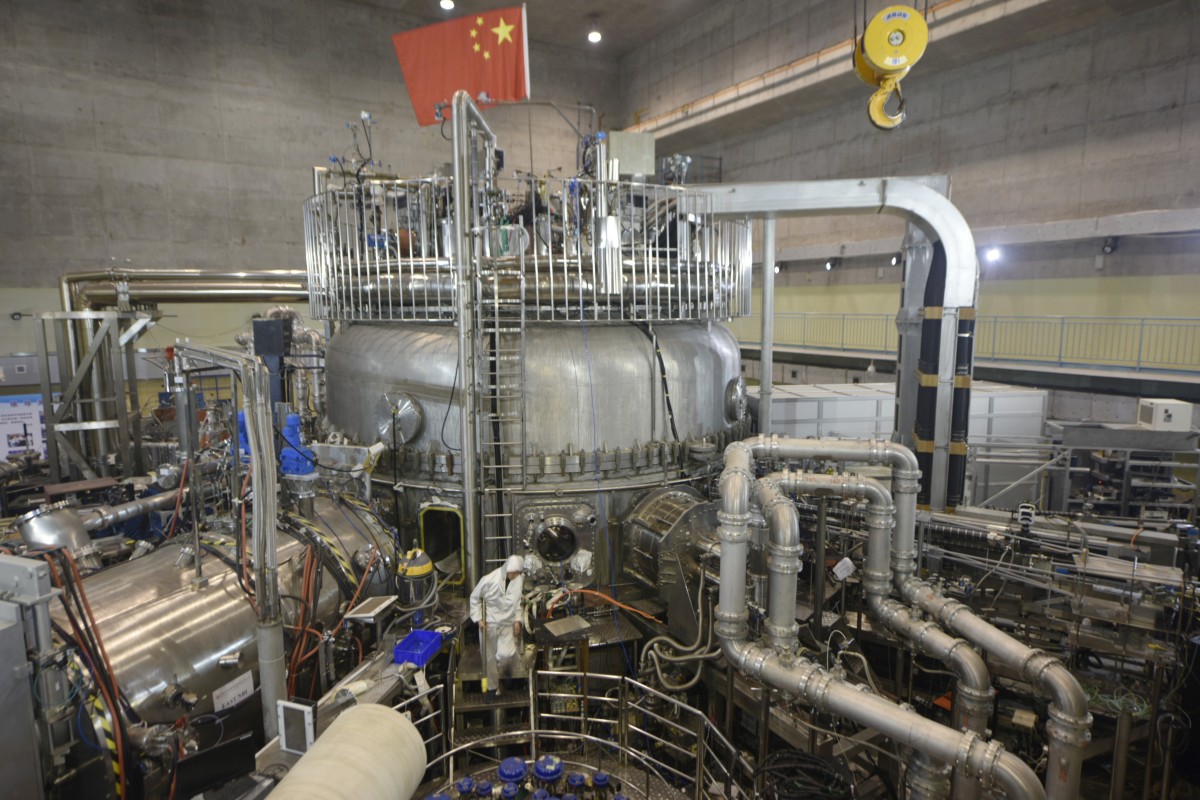

For China’s Communist Party, relaxing its grip on power means losing it. A page from the June 4, 1989, entry in the diary of Li Rui, one of Mao’s personal secretaries, with the heading ‘Black Week-end’

A page from the June 4, 1989, entry in the diary of Li Rui, one of Mao’s personal secretaries, with the heading ‘Black Week-end’

In April the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University hosted a conference on the life and times of

Li Rui, one of the most storied personalities in the history of the People’s Republic.

Li was an early member of the Communist Party and for a short while one of Mao’s personal secretaries, making him a gatekeeper to the man who ran the country like an emperor.

But after crossing Mao and his allies, Li ended up spending nearly twenty years in prisons or in exile. After his release in 1978, he served in a few government posts but mainly took up historical writing. He wrote an account of the Lushan Conference in 1959, at which Mao purged dissidents and doubled down on the disastrous economic policies surrounding what became one of the worst famines in history.

Li also helped found China Through the Ages, a journal that took on sensitive topics from the party’s history.

Over the past few years, Li and his daughter, Li Nanyang, have been moving his personal papers and photos to the Hoover archives.

Ms. Li took a position there to organize and transcribe the material, including years’ worth of diaries. Li died this past February, aged 101, and the conference was meant to assess his life and announce that the material would soon be made available to the public.

The steady flow of unofficial accounts of the past is another way that historical truth escapes the party’s clutches.

Li’s account of the Lushan Conference is part of a trend toward understanding Mao’s responsibility for the famine.

The official line is that the famine was caused by natural disasters or by the split with the Soviet Union that occurred around that time.

But thanks to Li and other Chinese and foreign scholars, it is impossible for any serious scholar, even inside China, to accept the government’s version.

Li’s archives will likely add to the body of evidence against Mao because they contain his personal journal of the Lushan meeting.

So will Li’s account of June 4, 1989.

He lived in a building reserved for high-ranking cadres near the Muxidi intersection in western Beijing.

It was there that the several armored units began their assault on the city and there that hundreds of ordinary Beijingers assembled to stop their progress toward the students in the square—acts of courage described by the writer

Liao Yiwu in his moving book,

Bullets and Opium: Real-Life Stories of China After the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

5

Liao spent seven years assembling a memorable series of portraits of the working-class people who defended Tiananmen Square and took the brunt of the casualties.

Li’s perspective is simpler because he witnessed the massacre unfold from his balcony.

But coming from a high-ranking party member, someone who had a reputation for being upright and uncompromising, it is damning.

His diary entry for June 4 begins with two English words, “Black week-end.”

It then goes on to describe how soldiers shot indiscriminately, including into his building, killing a neighbor.

Then he recounts phone calls with outraged party members and the opinion of a friend and former general, Xiao Ke, who had written Deng weeks earlier warning of the disastrous consequences of deploying the army in the capital:

Han Xiong’s call was deeply dejecting. What has the party been reduced to?

When I hung up, my tears could not stop flowing.

An Zhiwen called to ask about the situation; he sighed and wondered how it could be the party [that did this]!

The whole day I felt restless and constantly wanted to wail.

Xiao Ke predicted: [the party will be] condemned through the ages and [this event] will go down in history as a byword for infamy.

How long does it take for history to effect change?

Writing in the 1980s, after the famines, political witch-hunts, and turmoil of the party’s first thirty years in power, the Belgian sinologist Simon Leys compared its rule “to the aimless drift of a dead dog; only its belly, swollen with the windy promises of the ‘Four Modernizations,’ still keeps it vaguely afloat.”

Leys was right that the party’s embrace of economic development—subsumed under the slogan the “Four Modernizations”—was keeping it afloat.

In the intervening four decades, the party’s embrace of economic development has been wildly successful, so much so that it’s become possible to think of the party’s rule as inevitable and eternal.

But Leys was no idealist in seeing the party as already dead.

When he wrote those words—in his collection of essays The Burning Forest (1985)—he knew very well that the party’s corpse wouldn’t sink immediately.

He pointed to the experiences of the French Catholic priest Évariste Régis Huc, who traveled widely through China in the 1840s, following the Qing dynasty’s defeat in the First Opium War of 1839–1842.

Even though the Qing would not fall until 1911, Huc knew that it was finished.

“Yet it took another seventy years for the old empire actually to collapse,” Leys wrote.

“When operating on the scale of China, history adopts another rhythm.”

1. This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center. Thanks to Geremie Barmé for his dedication in collecting, promoting, and translating works about Xu’s case on the China Heritage website. ↩

2. For more on Bao Pu, see my “‘My Personal Vendetta’: An Interview with Hong Kong Publisher Bao Pu,” NYR Daily, January 22, 2016. On Zhao’s memoirs, see Jonathan Mirsky, “China’s Dictators at Work: The Secret Story,” The New York Review, July 2, 2009. Li Peng’s diaries were withdrawn from publication due to political pressure but are available online. ↩

3. An adaptation of Nathan’s introduction is available on the Foreign Affairs website. ↩

4. See, for example, Michael Fathers and Andrew Higgins, Tiananmen: The Rape of Peking (Doubleday, 1989), or sections in broader books such as Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, China Wakes: The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power (Random House, 1994), and Orville Schell, Mandate of Heaven (Simon and Schuster, 1994). ↩

5. Berlin: Fischer, 2012. An English translation, to which I contributed the introduction, has just been published by Atria. ↩