China is using LinkedIn to recruit Americans

By Warren Strobel, Jonathan LandayChinese spy nest

WASHINGTON -- The United States’ top spy catcher said Chinese espionage agencies are using fake LinkedIn accounts to try to recruit Americans with access to government and commercial secrets, and the company should shut them down.

William Evanina, the U.S. counter-intelligence chief, told Reuters in an interview that intelligence and law enforcement officials have told LinkedIn, owned by Microsoft Corp., about China’s “super aggressive” efforts on the site.

He said the Chinese campaign includes contacting thousands of LinkedIn members at a time, but he declined to say how many fake accounts U.S. intelligence had discovered, how many Americans may have been contacted and how much success China has had in the recruitment drive.

German and British authorities have previously warned their citizens that Beijing is using LinkedIn to try to recruit them as spies.

But this is the first time a U.S. official has publicly discussed the challenge in the United States and indicated it is a bigger problem than previously known.

Evanina said LinkedIn should look at copying the response of Twitter, Google and Facebook, which have all purged fake accounts allegedly linked to Iranian and Russian intelligence agencies.

“I recently saw that Twitter is cancelling, I don’t know, millions of fake accounts, and our request would be maybe LinkedIn could go ahead and be part of that,” said Evanina, who heads the U.S. National Counter-Intelligence and Security Center.

It is highly unusual for a senior U.S. intelligence official to single out an American-owned company by name and publicly recommend it take action.

Evanina said LinkedIn should look at copying the response of Twitter, Google and Facebook, which have all purged fake accounts allegedly linked to Iranian and Russian intelligence agencies.

“I recently saw that Twitter is cancelling, I don’t know, millions of fake accounts, and our request would be maybe LinkedIn could go ahead and be part of that,” said Evanina, who heads the U.S. National Counter-Intelligence and Security Center.

It is highly unusual for a senior U.S. intelligence official to single out an American-owned company by name and publicly recommend it take action.

LinkedIn boasts 562 million users in more than 200 counties and territories, including 149 million U.S. members.

Evanina did not, however, say whether he was frustrated by LinkedIn’s response or whether he believes it has done enough.

LinkedIn’s head of trust and safety, Paul Rockwell, confirmed the company had been talking to U.S. law enforcement agencies about Chinese espionage efforts.

Evanina did not, however, say whether he was frustrated by LinkedIn’s response or whether he believes it has done enough.

LinkedIn’s head of trust and safety, Paul Rockwell, confirmed the company had been talking to U.S. law enforcement agencies about Chinese espionage efforts.

Earlier this month, LinkedIn said it had taken down “less than 40” fake accounts whose users were attempting to contact LinkedIn members associated with unidentified political organizations. Rockwell did not say whether those were Chinese accounts.

“We are doing everything we can to identify and stop this activity,” Rockwell told Reuters.

“We are doing everything we can to identify and stop this activity,” Rockwell told Reuters.

“We’ve never waited for requests to act and actively identify bad actors and remove bad accounts using information we uncover and intelligence from a variety of sources including government agencies.”

Rockwell declined to provide numbers of fake accounts associated with Chinese intelligence agencies.

Rockwell declined to provide numbers of fake accounts associated with Chinese intelligence agencies.

He said the company takes “very prompt action to restrict accounts and mitigate and stop any essential damage that can happen” but gave no details.

LinkedIn “is a victim here,” Evanina said.

LinkedIn “is a victim here,” Evanina said.

“I think the cautionary tale ... is, ‘You are going to be like Facebook. Do you want to be where Facebook was this past spring with congressional testimony, right?’” he said, referring to lawmakers’ questioning of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg on Russia’s use of Facebook to meddle in the 2016 U.S. elections.

EX-CIA OFFICER ENSNARED

Evanina said he was speaking out in part because of the case of Kevin Mallory, a retired CIA officer convicted in June of conspiring to commit espionage for China.

A fluent Mandarin speaker, Mallory was struggling financially when he was contacted via a LinkedIn message in February 2017 by a Chinese posing as a headhunter, according to court records and trial evidence.

The individual, using the name Richard Yang, arranged a telephone call between Mallory and a man claiming to work at a Shanghai think tank.

During two subsequent trips to Shanghai, Mallory agreed to sell U.S. defence secrets -- sent over a special cellular device he was given -- even though he assessed his Chinese contacts to be intelligence officers, according to the U.S. government’s case against him.

He is due to be sentenced in September and could face life in prison.

While Russia, Iran, North Korea and other nations also use LinkedIn and other platforms to identify recruitment targets, the U.S. intelligence officials said China is the most prolific and poses the biggest threat.

U.S. officials said China’s Ministry of State Security has “co-optees” -- individuals who are not employed by intelligence agencies but work with them -- set up fake accounts to approach potential recruits.

The targets include experts in fields such as supercomputing, nuclear energy, nanotechnology, semi-conductors, stealth technology, health care, hybrid grains, seeds and green energy.

Chinese intelligence uses bribery or phony business propositions in its recruitment efforts.

While Russia, Iran, North Korea and other nations also use LinkedIn and other platforms to identify recruitment targets, the U.S. intelligence officials said China is the most prolific and poses the biggest threat.

U.S. officials said China’s Ministry of State Security has “co-optees” -- individuals who are not employed by intelligence agencies but work with them -- set up fake accounts to approach potential recruits.

The targets include experts in fields such as supercomputing, nuclear energy, nanotechnology, semi-conductors, stealth technology, health care, hybrid grains, seeds and green energy.

Chinese intelligence uses bribery or phony business propositions in its recruitment efforts.

Academics and scientists, for example, are offered payment for scholarly or professional papers and, in some cases, are later asked or pressured to pass on U.S. government or commercial secrets.

Some of those who set up fake accounts have been linked to IP addresses associated with Chinese intelligence agencies, while others have been set up by bogus companies, including some that purport to be in the executive recruiting business, said a senior U.S. intelligence official, who requested anonymity in order to discuss the matter.

The official said “some correlation” has been found between Americans targeted through LinkedIn and data hacked from the Office of Personnel Management, a U.S. government agency, in attacks in 2014 and 2015.

The hackers stole sensitive private information, such as addresses, financial and medical records, employment history and fingerprints, of more than 22 million Americans who had undergone background checks for security clearances.

The United States identified China as the leading suspect in the massive hacking.

UNPARALLELED SPYING EFFORT

About 70 percent of China’s overall espionage is aimed at the U.S. private sector, rather than the government, said Joshua Skule, the head of the FBI’s intelligence division, which is charged with countering foreign espionage in the United States.

“They are conducting economic espionage at a rate that is unparalleled in our history,” he said.

Five current and former U.S. officials -- including Mallory -- have been charged with or convicted of spying for China in the past two and a half years.

He indicated that additional cases of suspected espionage for China by U.S. citizens are being investigated, but declined to provide details.

U.S. intelligence services are alerting current and former officials to the threat and telling them what security measures they can take to protect themselves.

Some current and former officials post significant details about their government work history online -- even sometimes naming classified intelligence units that the government does not publicly acknowledge.

LinkedIn “is a very good site,” Evanina said.

Some of those who set up fake accounts have been linked to IP addresses associated with Chinese intelligence agencies, while others have been set up by bogus companies, including some that purport to be in the executive recruiting business, said a senior U.S. intelligence official, who requested anonymity in order to discuss the matter.

The official said “some correlation” has been found between Americans targeted through LinkedIn and data hacked from the Office of Personnel Management, a U.S. government agency, in attacks in 2014 and 2015.

The hackers stole sensitive private information, such as addresses, financial and medical records, employment history and fingerprints, of more than 22 million Americans who had undergone background checks for security clearances.

The United States identified China as the leading suspect in the massive hacking.

UNPARALLELED SPYING EFFORT

About 70 percent of China’s overall espionage is aimed at the U.S. private sector, rather than the government, said Joshua Skule, the head of the FBI’s intelligence division, which is charged with countering foreign espionage in the United States.

“They are conducting economic espionage at a rate that is unparalleled in our history,” he said.

Five current and former U.S. officials -- including Mallory -- have been charged with or convicted of spying for China in the past two and a half years.

He indicated that additional cases of suspected espionage for China by U.S. citizens are being investigated, but declined to provide details.

U.S. intelligence services are alerting current and former officials to the threat and telling them what security measures they can take to protect themselves.

Some current and former officials post significant details about their government work history online -- even sometimes naming classified intelligence units that the government does not publicly acknowledge.

LinkedIn “is a very good site,” Evanina said.

“But it makes for a great venue for China to target not only individuals in the government, formers, former CIA folks, but academics, scientists, engineers, anything they want. It’s the ultimate playground for collection.”

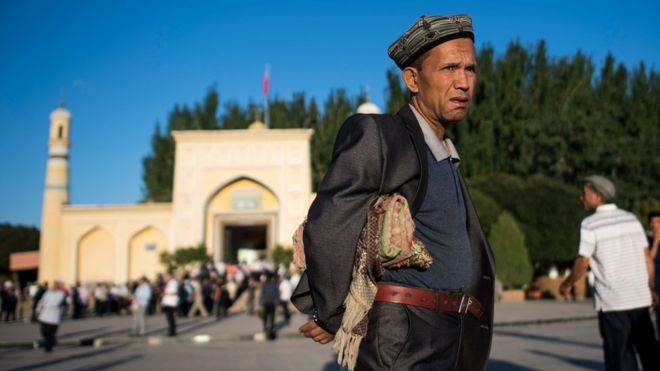

The UN commission says China discriminates against its Uighur population.

The UN commission says China discriminates against its Uighur population.

A woman stands behind a pillar during the Eid al-Adha festival at a Chinese mosque.

A woman stands behind a pillar during the Eid al-Adha festival at a Chinese mosque.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.