By Andrew Higgins

The Chinese city of Heihe seen from Blagoveschensk, Russia. The lettering on the building reads ”Go Wuhan.”

The Chinese city of Heihe seen from Blagoveschensk, Russia. The lettering on the building reads ”Go Wuhan.”BLAGOVESHCHENSK, Russia — With a contagious illness raging in China, just 600 yards away across the frozen Amur River, the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Russian border city of Blagoveshchensk thundered with promises of salvation from the plague.

“A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you,” promised Dmitri Zhang, a Chinese Orthodox priest, reciting a psalm offering deliverance for those of faith from the “pestilence that stalks in darkness.”

The special prayer service on Sunday, featuring pleas for mercy in both Russian and Chinese from the Chinese coronavirus and attended by worshipers from both countries, displayed just how intertwined the fortunes — and now the misfortunes — of the two countries have become.

It showed as well how the destructive effects of the Chinese virus can be felt even in a far-flung outpost like Blagoveshchensk, where it has yet to infect a single person.

Until the Chinese virus started killing people in Wuhan, China, and spreading fear far beyond, Blagoveshchensk had staked its future on ever-closer relations with China, harnessing its economy to burgeoning cross-border commerce and a flood of traffic across the river, by boat in summer and over a pontoon bridge laid on the ice in winter.

At Three Whales, a big market in the center of Blagoveshchensk, only a few customers walked among the stalls.

Chinese language instruction for Russian youngsters at the Blagoveschensk State Pedagogical University.

With the border now closed on orders from Moscow, this has all ground to a halt, leaving the city frozen in limbo.

Businesses that depend on China are shriveling, hotels once full of Chinese guests stand empty and the local university, once a magnet for paying pupils from China, is struggling to cope as hundreds of its students who went home for the Lunar New Year holiday find themselves stranded.

A road bridge, the first across the Amur River and the 1,140 mile stretch of border it demarcates, was completed last November.

But the huge structure never opened to traffic and now stands marooned in the snow and ice, a monument to hopes suddenly dashed, or at least delayed, by the spread of the disease.

Also suffering is China’s image as a benign force from which Russia can only reap benefit.

This is slowly being eclipsed by anxiety over China’s new, unwelcome role as a source of disease, agonizing uncertainty and frustrated hopes.

“Everything is at a standstill,” said Julia Tavitova, the general director of Amurturist, a Russian company that had depended on visitors from China to fill a hotel it operates on the Russian bank of the Amur.

“It is a chain reaction. One by one, businesses are getting killed by this disease.”

She has let go half her company’s staff.

Li Lihua, second from right, a Russian-speaking Chinese businesswoman, in her restaurant “Omega.” Ms. Li, who has been working in Blagoveshchensk since the 1990s, said this was the worst economic situation she has encountered.

A Chinese-run shop at the central market, where business has fallen off a cliff.

Blagoveshchensk’s biggest hotel, Asia, built to house throngs of visitors from China, is now a ghost ship, its 18 floors mostly empty of guests.

Nearby shops selling jewelry, gold and other products popular with Chinese buyers have lost nearly all their business.

Fearful that the presence of Chinese guests at her company’s own hotel, the Druzhba, or Friendship, might drive away other regular customers, Ms. Tavitova last month decided to bar Chinese from booking rooms.

“We could not risk losing everything,” she explained.

The Kremlin last week made the same calculation, announcing that, starting last Thursday, all Chinese citizens would be barred from entering Russia.

The decision slammed a lucrative tourism industry driven in a large part by Chinese visitors, more than 1.5 million of whom came to Russia last year.

Heihe, the Chinese city on the other side of the river, has several confirmed coronavirus infections in the district under its jurisdiction, while the surrounding province of Heilongjiang has nearly 500 officially reported cases and possibly many more.

Giant neon signs, clearly visible from the Russian side, flash constant reminders of the crisis, displaying the Chinese Communist Party’s rallying cry: “Go Wuhan, Go China.”

But the party’s message is written in Chinese so few Russians understand it.

In Blagoveshchensk, there is no sign of panic or even mild alarm, just anger at a spike in vegetable prices after deliveries from China stopped.

Virtually nobody wears a face mask, despite an order from the authorities that this be done in schools and many other public places.

But the proximity of so much potential danger has, on social media, stirred a frenzy of fear-mongering and rumors — that the Chinese virus was created in a secret Chinese or, alternatively, American laboratory; that infected Chinese have slipped across the border; and that the Blagoveshchensk airport will soon be closed and the city sealed.

A new road bridge over the Amur River was completed in November but has yet to be opened to traffic.

Chinese students in Blagoveschensk sitting behind a Lenin statue. Hundreds of others have been trapped in China after the border was closed.

“People call from Moscow and ask, ‘Are you still alive out there?’” said Andrey V. Druzyaka, an associate professor in history at the Blagoveshchensk State Pedagogical University.

Li Lihua, a Russian-speaking Chinese businesswoman, has been working in Blagoveshchensk since the 1990s, surviving repeated economic and political crises to build up a small empire of restaurants, factories and real estate projects.

The current paralysis, she said, is far worse than previous trials.

The Chinese laborers she needs to finish building four 10-story apartment blocks on the outskirts of Blagoveshchensk cannot enter Russia, and nobody in Russia, she said, wants to get involved with a venture so dependent on China.

At Three Whales, a big market in the center of Blagoveshchensk, a few customers recently roamed stalls mostly run by Chinese traders.

Wang Wencheng, who sells Chinese-made sports gear, said sales had plummeted.

He wears a face mask to reassure his few remaining customers.

With many fellow traders stuck on the other side of the river, their stalls have been shrouded in blue tarpaulins that make them look like a crime scene.

Tatiana Kapustina, who runs a business with her husband exporting artisanal honey, mostly to China, said sales, which last year reached metric 50 tons, had fallen to “a total of zero” this year.

“China is not going to collapse, but nobody knows when and how this will all end,” Ms. Kapustina said.

“Uncertainty is our biggest problem.”

Just three months ago, Blagoveshchensk and Heihe were celebrating the completion of the bridge connecting the two countries across the Amur, a tangible example of how Russia and China have overcome the suspicion, fear and outright hostility that flowed for decades along the river and even led to a brief war in 1969.

Wang Wencheng, who sells Chinese-made sports gear at the Three Whales market, said sales had plummeted.

The almost empty Three Whales market. The central government in Moscow barred all Chinese citizens from entering Russia.

Suspicion is now creeping back, fanned by strident nationalist voices on social media and gossip on the street.

In Volkovo, a poor village outside Blagoveshchensk, the regional health authorities have turned a two-story clinic into a quarantine center for Chinese who crossed the border after the outbreak.

The head of the village administration, Dzhasur Samandof, said he had no problem with the quarantine center but was tired of fielding angry questions from residents in a panic over untrue rumors — of sick Chinese wandering village streets, and of a school canteen next to the quarantine center sharing cutlery with possibly infected Chinese.

Nikolai Kukharenko, a co-director of Blagoveshchensk’s Confucius Institute, part of a Beijing-funded program to spread the teaching of Chinese abroad, said social media had played a particularly noxious role in spreading fear, noting that a 2003 outbreak of the more lethal SARS virus in China had stirred little concern in Russia.

A painting by Vasili Romanov depicting the signing of the 1858 Aigun Treaty, which established much of the modern border between Russia and China.

Father Dmitry Zhang, a Chinese orthodox priest, celebrating a special service in response to the Chinese coronavirus outbreak.

Mr. Kukharenko was appalled this month by the reaction online to photographs he posted of face masks he had collected for delivery to China.

Russian patriots assailed him as a traitor, who had forgotten that “China is not an ally but our most important potential opponent and enemy.”

Such views don’t represent mainstream opinion in Blagoveshchensk, but a relationship whose momentum had seemed unstoppable is suddenly stuck.

Whether it can start moving again will depend largely on how fast China’s idled economy starts up — and starts consuming the oil and gas that underpin relations between Moscow and Beijing.

Power of Siberia, a new 1,800-mile gas pipeline that opened in December to carry natural gas from Siberia to China, passes under the Amur in Blagoveshchensk.

North of the city, Gazprom is building the world’s biggest gas processing plant, largely to serve China.

A more immediate problem, however, is getting the border open again.

Of the more than 200 Chinese students enrolled at the State Pedagogical University in Blagoveshchensk, only a few are now attending class.

Luan Bohan, a 22-year-old Chinese student who stayed in Russia over the Lunar holiday, said he had encountered no overt discrimination.

But, he added, children who see him on the street with his face mask sometimes point and shout “Chinese virus, Chinese virus” before running away.

Some residents, though, particularly those who see China as Russia’s best hope of resisting the West, blame the United States for the outbreak.

Aleksandr Kozhin, a Russian who lives mostly in Heihe but is now stuck on the Russian side of the river, thinks a secret American laboratory could have created the Chinese coronavirus as a weapon to undermine China’s success and image.

And regardless of where the Chinese virus comes from, he added, Russia has nothing to fear: “Two hundreds grams of vodka will kill any Chinese virus.”

Illuminated skyscrapers in Heihe can be seen from almost everywhere in Blagoveschensk.

For decades, a

For decades, a

Patients line up in an outpatient department at a hospital in Wuhan.

Patients line up in an outpatient department at a hospital in Wuhan.

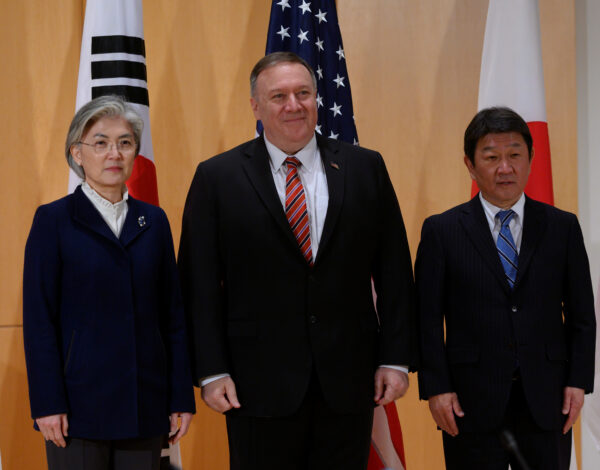

The Beijing stooges: World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergencies Programme head Michael Ryan, left, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and WHO Chair of Emergency Committee on Ebola Robert Steffen attend a combined news conference after a two-day international conference on Chinese coronavirus vaccine research.

The Beijing stooges: World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergencies Programme head Michael Ryan, left, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and WHO Chair of Emergency Committee on Ebola Robert Steffen attend a combined news conference after a two-day international conference on Chinese coronavirus vaccine research.  Chinese Premier Li Keqiang flew into Wuhan at the end of last month, but it appears Xi Jinping has no plans to inspect the epicenter of the contagion.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang flew into Wuhan at the end of last month, but it appears Xi Jinping has no plans to inspect the epicenter of the contagion.