By David Barboza, Marc Santora and Alexandra Stevenson

The Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, center right, welcoming Milos Zeman, center left, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 2015. Ye Jianming, far left, headed CEFC China Energy, which spent more than $1 billion on deals in the Czech Republic.

PRAGUE — When Xi Jinping became the first top Chinese leader to visit the Czech Republic, he was accompanied by a mysterious Chinese tycoon with big political ambitions, money to burn and strong ties to the Czech president.

Ye Jianming was the sole businessman among the group of Chinese and Czech government officials who gathered two years ago outside the presidential summer residence where Xi and Milos Zeman, his Czech counterpart, planted ginkgo trees.

For Ye, it was recognition of his role as a major power broker in Prague, having bought landmark properties, a local brewery and a much beloved soccer team.

The meeting — and the Ye's presence — cemented China’s newfound influence on politics and business in Zeman’s Czech Republic and signaled its broader ambitions in Europe.

In just two years Ye’s company, CEFC China Energy, had spent more than $1 billion on deals in the Czech Republic.

He hired former Czech officials, including a onetime defense minister.

Ye was even named a special economic adviser to Zeman.

Zeman, in turn, became a big backer of Beijing, tamping down domestic opposition to Chinese influence and taking up Chinese causes.

He publicly supported China’s claims over Taiwan, the democratic island that Beijing claims as its territory.

When Xi visited, police tried to keep protesters out of sight; some later accused the police of using violence to suppress them.

The family of a prominent Holocaust survivor said Zeman withdrew a proposed medal for the man after his nephew met with the Dalai Lama, an exiled spiritual leader whom China considers a rebel.

China's fifth column: Xi's myrmidons demonstrated during his visit in Prague in 2016.

For China, the Czech courtship was an unqualified victory: It had won a sure friend in Europe,

an American military ally and a country once seen as a bulwark for liberal democracy in a strategically important region.

As Zeman declared, the Czech Republic hoped to become “an unsinkable aircraft carrier of Chinese investment expansion” in Europe.

Then, Ye was detained in China this year, exposing the Czech Republic to the perils of this new relationship and forcing the president to defend his quick embrace of the Chinese deal maker.

While the reason for Ye’s detention was never made public, critics of the Czech president saw Ye’s disappearance as proof that the country shouldn’t have tied its future and its fortune to the Chinese.

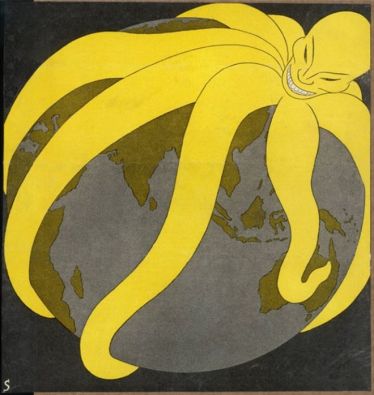

An emboldened, globally ambitious China is using money, business deals and other incentives to extend its power abroad.

The pitch can hold great appeal in a world shaken by Washington’s growing disengagement and Europe’s struggles.

But tighter ties to China mean greater susceptibility to an opaque political system where decisions are made behind the scenes.

Investments can be driven by politics rather than economics, resulting in costly white elephants.

In the Czech Republic, Ye’s sudden disappearance took the country’s leaders by surprise.

They couldn’t discern why that would happen to someone who seemed to have the government’s blessing.

They had not pressed him on where he was getting his money to make big flashy deals in the Czech Republic and elsewhere.

He soon found out.

Prague was about to become even more enmeshed with the Chinese government.

A state-owned company stepped in to take control of Ye’s empire, fueling suspicions that the company was politically important to the Chinese leadership.

Xi and Zeman during a welcome ceremony outside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 2014. Zeman’s visit was the first by a Czech leader in nearly a decade.

Eastern Appeal

Early in his political career, Zeman, a blunt-spoken populist, warned against toadying up to Russia and China.

Those seeking deeper ties with Beijing,

he told a local newspaper in 1996, are “ready to go under plastic surgery to slant their eyes.”

But the realities in Europe were changing by the time he won the Czech presidency in 2013.

The global financial crisis had tested Europe’s unity.

Refugees from Syria had begun to arrive, fueling nativist sentiment and pitting local politicians against the bloc’s leaders.

Western Europe no longer seemed to be the only option.

At the time, Beijing was beginning to pour money and political capital into Eastern and Central Europe as part of a broad bid to increase its heft in Europe.

China’s leaders see the region as potentially fertile ground.

While Britain, France and Germany welcomed greater investments from Beijing, they still bucked China’s stances on issues like human rights and its claim to control

almost all of the South China Sea.

Eastern and Central Europe didn’t have the same qualms.

Looking for further inroads, China started what came to be called the

16+1 initiative, an effort to expand cooperation with more than a dozen Eastern and Central European nations.

Xi later included Eastern and Central Europe in his Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious plan to develop economic and diplomatic ties through infrastructure projects around the world.

China’s influence in Europe is already apparent.

Greece and Hungary worked to water down a 2016 European Union statement regarding the South China Sea.

For Zeman, the courtship basically had to start from scratch.

The former Czechoslovakia recognized the Communist-led China in 1949, but a

rift between Moscow and Beijing kept them apart.

The post-Soviet Czech Republic, remembering

the brutal 1968 Soviet crackdown on reform efforts in Prague and subsequent Communist domination, found common cause with Beijing’s critics.

Vaclav Havel, the anti-Communist activist and the country’s first leader after the fall of the Berlin Wall, invited the

Dalai Lama to a state visit in 1990, angering Beijing.

He had stern words for China.

“Intimidation, propaganda campaigns, and repression,” he wrote, “are no substitute for reasoned dialogue.”

The Piraeus Container Terminal, operated by the Chinese state-owned shipping company Cosco in Athens. Greece, which has received significant Chinese investment, blocked a European Union statement in the United Nations criticizing China’s human rights record.

Zeman, a well-known smoker and drinker who once publicly denied that

he showed up at his inauguration drunk, broke with that history.

He rejected Havel-era support for the Dalai Lama and its close ties to the government of Taiwan.

He visited China in 2014, the first visit by a Czech leader in

nearly a decade.

A year later,

he was the only European Union leader to attend a military parade celebrating the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

That helped him secure Xi’s 2016 visit to Prague.

“This is a restart,” Zeman told Chinese official media before Xi’s visit, adding that the previous government had been “very submissive” to the United States and the European Union.

“Now, we are again an independent country,” he said, “and we formulate our foreign policy, which is based on our own national interests, and we do not interfere with the internal affairs of any other country.”

His focus on China won wide praise from the Czech political apparatus.

“If anybody thinks that under current circumstances it is possible to create safe and prosperous world without cooperation with China, then he has missed the train long ago,” said Katerina Konecna, vice chairman of the Czech Republic’s Communist Party.

Zeman’s office said its efforts to court China were no different from the efforts of others.

“Those that have expressed such criticism offend our Western allies who collaborate extraordinarily tightly with the People’s Republic of China,” said Jiri Ovcacek, a spokesman for Zeman.

Zeman’s office didn’t respond to further requests for comment.

CEFC’s European headquarters in Prague. The company bought a stake in one of Prague’s biggest office complexes. It invested in the Czech national airline, two hotels and a pair of Renaissance-era buildings. It also bought a brewery that traces its roots back more than 700 years.

A Shadowy Suitor

Zeman’s 2014 visit proved fateful for the Czech Republic.

Among the business deals reached was a cooperation pact between a Czech financial firm and an up-and-coming energy company called CEFC.

It was led by Ye Jianming, who was born in a small village in the southern Chinese province of Fujian.

He grabbed hold of assets once controlled by a notorious smuggler and in a few years parlayed them into a sprawling business empire with 30,000 employees.

Ye traveled the world on his twin-engine Airbus 319 private jet, meeting heads of state, Russian oligarchs and the crown prince of Abu Dhabi.

CEFC was modeled on Xi’s vision of a stronger China — and it went where Xi wanted China to go. It struck deals in the United Arab Emirates and Kazakhstan.

It courted top leaders in places like Albania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Sudan and Uganda.

Last year, it agreed to buy a $9 billion stake in Rosneft, the Russian oil giant, which put it firmly in the middle of the complicated but important relationship between Beijing and Moscow.

Its fast rise fueled rumors in China that Ye had ties to Xi, who once worked in Fujian, or other Chinese leaders.

CEFC did little to discourage them.

On its website, CEFC cited the military and Communist Party experience of its top executives.

The Czech Republic made a tempting target for CEFC’s international push.

The country was a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, was disillusioned with the West and ready to do business.

CEFC bought a stake in Florentinum, one of Prague’s biggest office complexes.

It invested in the Czech national airline, two hotels and a pair of Renaissance-era buildings.

It bought a brewery that traces its roots back more than 700 years.

Zeman’s staff trumpeted the deals as proof that courting China made economic sense.

“People believed the rhetoric,” said

Olga Lomova, the head of the

Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation International Sinological Center of Charles University in Prague.

“We have the Chinese. We will be happy again.”

CEFC also hired figures close to Zeman, leading to accusations from critics of a revolving door between the Chinese company and the president.

Jaroslav Tvrdik, the country’s former minister of defense, was hired to run CEFC’s Czech operations while serving as an adviser on China to the government.

Czech officials defended keeping Tvrdik as an adviser, saying the position was unpaid.

Miroslav Sklenar, Zeman’s protocol chief, left that position in 2015 for a role at CEFC.

He returned to the presidential palace at the end of 2016.

Early on, CEFC worried that its growing involvement would upset the public.

Its solution: Buy the local soccer team.

Slavia Prague had been on the brink of bankruptcy when CEFC purchased a majority stake in 2015. The team’s uniforms were changed to say “CEFC China” in Roman letters and in Chinese characters.

Slavia Prague had been on the brink of bankruptcy when CEFC purchased a majority stake in 2015. The team began to spend heavily under its new owner, retaining its star forward, Milan Škoda, and signing a Dutch player, Gino van Kessel.

Last year, the club won its first league championship since 2009.

Slavia Prague played in uniforms that said “CEFC China” in Roman letters and in Chinese characters.

CEFC’s deals made little business sense to observers.

“So many of the acquisitions were made in a rush, and were nonsense,” said Ms. Lomova, of Charles University.

“They were not investments that were able to pay for themselves.”

And CEFC acknowledged that its motivations went beyond business.

“Our company cares about what we can do to bridge the cultural gap,”

Jiang Chunyu, a senior executive at CEFC said at a forum in China in December.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.

Promises Undone

Xi’s historic 2016 visit to Prague showed the China-Czech relationship to be the closest in the history of the two countries.

It also showed that cracks were forming.

Thousands of protesters tried to greet the Chinese leader as he met with Zeman in Prague Castle. Members of both the Czech and European parliaments joined.

One lawmaker, who owns a home on the hill beneath the castle, set up a projector to cast the words “Truth and Love” on the castle wall — an invocation of a famous quote of Havel’s, who said that truth and love would vanquish lies and hatred.

Flags lining Xi’s route from the airport were defaced.

Czech authorities, with the help of CEFC, tried to obscure the tensions.

Police officers blocked demonstrators from getting too close to the castle, setting off complaints from protesters about police violence.

“Why are the police protecting the Chinese and limiting the ability of the Czech people to express themselves?” said

Ondrej Kolar, the mayor of a Prague district.

Wherever Xi traveled, busloads of local Chinese supporters appeared, too.

Filip Lexa, a 33-year-old teacher and doctoral student studying Chinese literature, said he showed up with a flag representing the

Uighur minority of western China, where the authorities there have cracked down on the local population.

He said he was harassed by a group of Chinese men bused into the event.

“When I took the flag out, everyone attacked me,” he said, adding that he escaped serious injury. “They pulled me into the middle of this group and started kicking me and hitting me with the flag poles they were carrying. One even broke a pole on my back.”

CEFC played a major role in trying to make sure the Chinese dictator’s visit went smoothly, said Mr. Kolar, the mayor who was involved in preparations for the event because his district is home to a number of embassies.

“It wasn’t organized by the state, but by a private company,” he said.

“CEFC organized the whole event.”

CEFC arranged for the display of Chinese flags along the route through Mr. Kolar’s neighborhood — flags with red and yellow color reminiscent of the Soviet Union.

When some were defaced, CEFC workers replaced them.

“It felt like the ’70s or ’80s again,” Mr. Kolar said.

“Then it was revealed that it was CEFC who paid for those flags.”

Many Czechs had other reasons to sour on the relationship with China.

Investment figures have proved disappointing — Taiwan’s investment in 2017 was nearly three times that of China’s, according to data from Sinopsis, a research group focused on China.

George Brady, an 88-year-old Holocaust survivor, was set to be honored at a Czech state dinner in 2016 and receive a medal for his work.

His sister,

Hana Brady, died in the gas chambers in Auschwitz, and he had turned her story into a popular children’s book called

“Hana’s Suitcase.”

But his nephew was the Czech Republic’s culture minister — and he was set to meet with the

Dalai Lama.

Before the ceremony, the nephew, Daniel Herman, received a call from Zeman’s office.

“I was told that if I went ahead with a meeting with the Dalai Lama, there would be no medal,” Mr. Herman said in an interview.

He went ahead with the meeting.

“And there was no ceremony,” he said.

Czech officials acknowledged that Zeman asked Mr. Herman not to meet with the Dalai Lama.

They said the withdrawal of the medal was unrelated, although they did not specify a reason.

Zeman, right, and Xi on the terrace of the Strahov Monastery overlooking Prague. Xi’s historic 2016 visit showed the China-Czech relationship to be the closest in the history of the two countries.

But China’s biggest challenge to its Czech strategy began elsewhere.

In November, American authorities arrested Patrick Ho, a top executive of CEFC’s nonprofit arm, and charged him with offering bribes to officials in Uganda and Chad in exchange for oil rights.

Czech officials and one person with direct knowledge of Ye’s case say he was detained by the Chinese authorities after Ho’s arrest.

A short time later, the company was hit with a number of problems.

Its bid for a stake in Rosneft collapsed.

And Chinese rating firms warned that CEFC had taken on considerable debt.

In April, Zeman met with officials from

Citic Group, a state-controlled Chinese company that had agreed to

buy just under half of CEFC’s Europe venture.

While Ye’s ties to China’s leadership had been just rumored, Citic is a company firmly under Beijing’s control.

Citic didn’t respond to requests for comment.

If a direct role for Beijing in Czech businesses bothered Zeman, he has shown little public sign.

He is set to make

another visit to the Chinese capital this autumn.

A security guard at the entrance of an unmarked building in Shanghai listed as an address for CEFC.

In this photo taken Friday, March 1, 2019, a woman walks by Chinese flag placed on a street in Belgrade, Serbia.

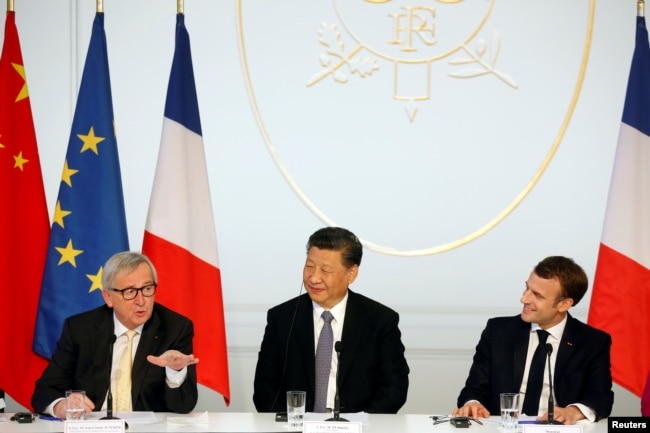

In this photo taken Friday, March 1, 2019, a woman walks by Chinese flag placed on a street in Belgrade, Serbia. French President Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker hold a news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Elysee presidential palace in Paris, France, March 26, 2019.

French President Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker hold a news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Elysee presidential palace in Paris, France, March 26, 2019. Power grid stand against the residential and office buildings in Beijing as the capital of China is shrouded by mild pollution haze on June 5, 2017.

Power grid stand against the residential and office buildings in Beijing as the capital of China is shrouded by mild pollution haze on June 5, 2017.

Taiwan’s embassy in San Salvador. El Salvador’s decision to cut ties leaves the Taipei government with just 17 formal diplomatic partners.

Taiwan’s embassy in San Salvador. El Salvador’s decision to cut ties leaves the Taipei government with just 17 formal diplomatic partners.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.