Director Nanfu Wang discusses her shocking, award-winning new documentary and the dangers she faced while making it.

By Charles Bramesco

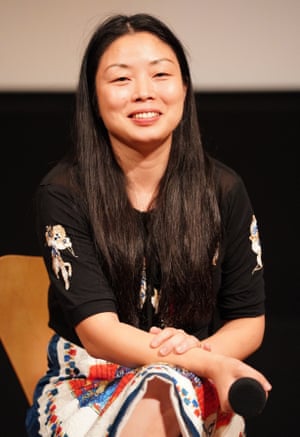

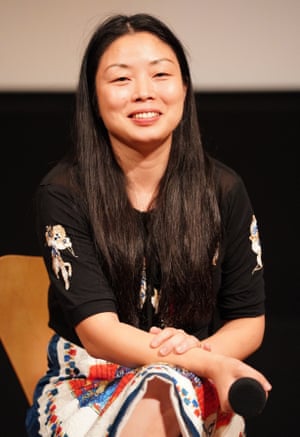

Nanfu Wang.

Nanfu Wang.

One Child Nation spans the personal and political, alleging that the political doesn’t get much more personal than when it’s dictating what is and isn’t allowed to happen inside your uterus.

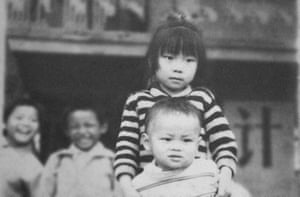

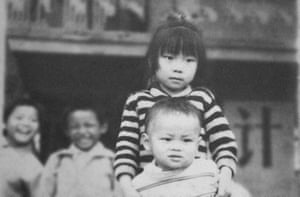

An archival photo of Nanfu Wang and her brother used in One Child Nation.

Getting away with it is getting away with it, however, and Wang has completed an incisive, edifying look into the darker corners of the national culture.

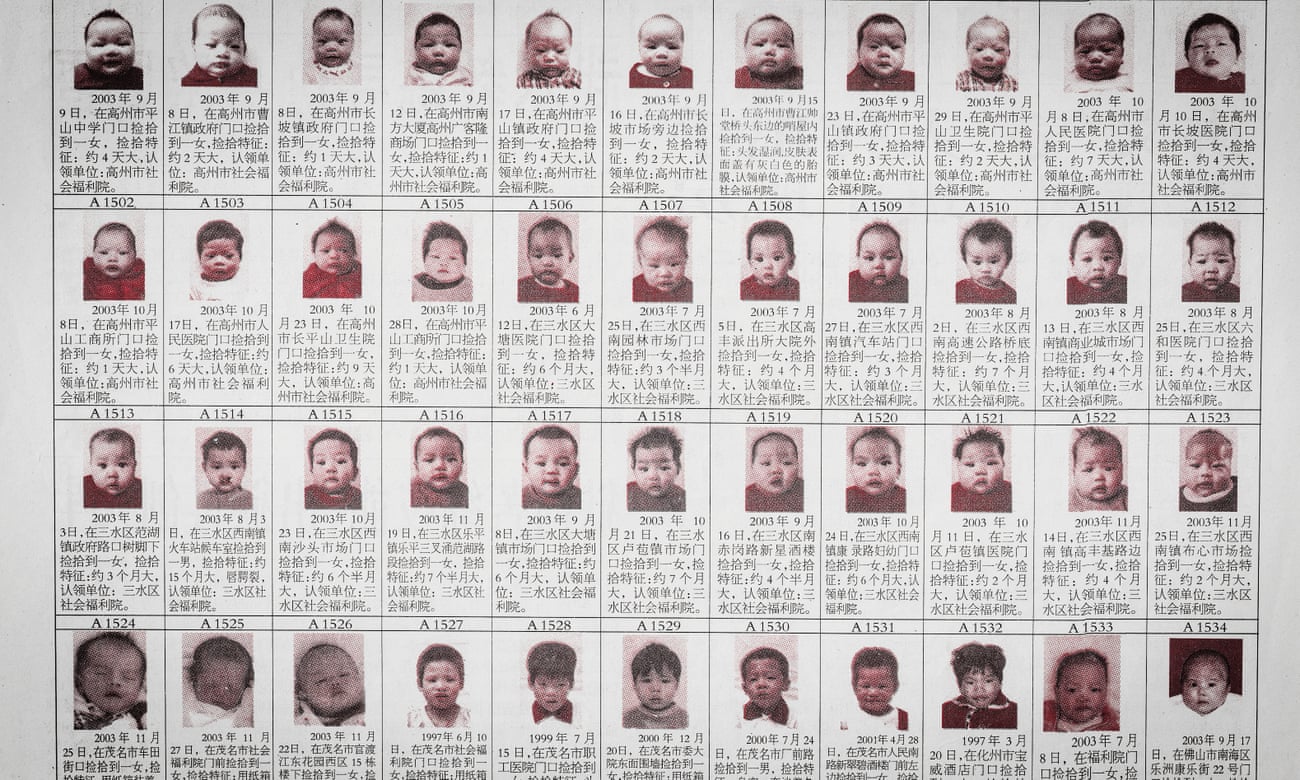

A found child advertisement, in a still from One Child Nation.

Authoritarian states have a quiet, insidious way of dressing up the immoral in the dowdy finery of the bureaucratically sanctioned.

Authoritarian states have a quiet, insidious way of dressing up the immoral in the dowdy finery of the bureaucratically sanctioned.

To an audience member sitting for Nanfu Wang’s harrowing new documentary One Child Nation, China’s former policy of permitting one infant per family (later amended to two, in the event of a first-born daughter) comes across as frightful stuff, at times borderline dystopian.

A western audience would be shocked to hear the elderly speak so nonchalantly on such morbid matters.

But Wang wanted to reveal the banality of this particular evil, to show how history can warp the perspective of those living through it.

“Before making this film, I had more judgment for the older generation, how they seemed to be closed-minded,” Wang tells the Guardian over the phone, not 24 hours before Amazon puts her film in American theaters for the widest release of the film-maker’s young career.

“Before making this film, I had more judgment for the older generation, how they seemed to be closed-minded,” Wang tells the Guardian over the phone, not 24 hours before Amazon puts her film in American theaters for the widest release of the film-maker’s young career.

“After finishing production, going through the process of conducting interviews and looking at the propaganda material, I started to understand why an entire nation of people would behave a certain way. I have more empathy towards the way that they behaved and the way that they think. They’ve lived their whole life in a society that discouraged or punished citizens who thought independently.”

In a sense, Wang took the one-child policy for granted in a negative capacity, just as her parents had taken it for granted as a way of life.

In a sense, Wang took the one-child policy for granted in a negative capacity, just as her parents had taken it for granted as a way of life.

It was a fact of the everyday for as long as she can remember; she was born in 1985, just a few years prior to her brother, meaning she was one flip of the genetic coin away from being left in a basket on the street.

Wang grew up around the cheery murals championing the brave patriots contributing to the effort to stem overpopulation, and she began to see through them at a young age.

As she grew into adulthood, she put that facet of her past behind her, until two wrinkles of fate brought the one-child policy back to the fore of her mind.

As she grew into adulthood, she put that facet of her past behind her, until two wrinkles of fate brought the one-child policy back to the fore of her mind.

First, China revoked the controversial legislation in 2015, allowing happy couples to freely go forth and multiply.

Second, Wang got pregnant herself, and instantly saw motherhood through fresh eyes.

“I remember just two weeks after I found out I was pregnant, how protective I became,” Wang explains.

“I was super aware of the dangers that could potentially face my unborn child’s safety and life. I wasn’t a very fearful person, but I noticed how much I was afraid for the life I was carrying. It was around then that I started thinking about other women who couldn’t protect their child, people who had to live every day under the fear of not knowing what would happen with their pregnancy. It was inconceivable for me to imagine living that life.”

Upon hearing that China’s government had painted the draconian policy as a humanitarian success – it claimed to have struck the laws only because they had performed their desired function, not due to the harm they caused – Wang wanted to rewrite the narrative.

Upon hearing that China’s government had painted the draconian policy as a humanitarian success – it claimed to have struck the laws only because they had performed their desired function, not due to the harm they caused – Wang wanted to rewrite the narrative.

She had observed the gaps that the Chinese state intentionally created in its public’s awareness of the Tiananmen Square demonstration and the Cultural Revolution, and she didn’t want to see young people losing touch with this particular shame.

“In China, the narrative about the one-child policy was overwhelmingly positive, and China’s influence has been growing outside of the nation,” she says.

“The narrative has traveled. A lot of Western media has adopted the Chinese authority’s narrative, so hopefully, the film can provide a counter-narrative.”

Nanfu Wang.

Nanfu Wang. One Child Nation spans the personal and political, alleging that the political doesn’t get much more personal than when it’s dictating what is and isn’t allowed to happen inside your uterus.

Wang started recording conversations with her parents and moved on to their contemporaries, learning how something as bureaucratic as federal mandates could have such a terribly intimate effect on those affected by them.

“I asked my mom what it was like for her when she was pregnant with me,” Wang recalls.

“She started telling me stories that I didn’t know, things I sort of knew but didn’t really remember or register. I processed what this all meant for the first time, and it got me wondering what else I didn’t know. I wanted to explore.”

But exploration, especially the kind that casts the government in a critical light, isn’t always so simply done in China.

But exploration, especially the kind that casts the government in a critical light, isn’t always so simply done in China.

Wang took what might seem like extreme precautions, only to witness first-hand how gravely necessary they were.

Jialing Zhang, Wang’s co-director and pal from back at NYU, would track her collaborator’s movements in China using GPS signaling while she stayed safe in the states.

Wang avoided hotels, public transportation, and other situations that could require her to expose her identity.

She recounts one nail-biter of a story in which an unsettling vibe cut a meeting with a former abortionist short, as both parties wordlessly parted at different, randomly selected train stops.

“We had created emergency plans, with lawyers on the ground in China who would be willing to help us,” Wang says.

“Even with that, there were several moments that felt scary.”

She continues: “We have not yet been contacted or confronted by the government. But we have noticed that there’s been censorship already. In China, they have a web site that’s an equivalent to IMDb, with people making their own pages for films in release. Back in January, when our film premiered at Sundance, the page that had been created for One Child Nation was taken down in a matter of days. If you click the title now, it’ll say ‘this page does not exist’. When Sundance announced their awards, China reported on the winners, and we were the only one missing from the list.”

She continues: “We have not yet been contacted or confronted by the government. But we have noticed that there’s been censorship already. In China, they have a web site that’s an equivalent to IMDb, with people making their own pages for films in release. Back in January, when our film premiered at Sundance, the page that had been created for One Child Nation was taken down in a matter of days. If you click the title now, it’ll say ‘this page does not exist’. When Sundance announced their awards, China reported on the winners, and we were the only one missing from the list.”

An archival photo of Nanfu Wang and her brother used in One Child Nation.

Getting away with it is getting away with it, however, and Wang has completed an incisive, edifying look into the darker corners of the national culture.

One Child Nation represents a bold step toward rewriting posterity, of ensuring that the history books will remember the forced sterilization and cries of lost babies instead of the paintings of smiling three-person family units.

At the same time, Wang remains unshakably focused on the human element, giving her interview subjects the chance to justify themselves.

“Eventually, I asked myself what I would do if I was in their position,” Wang confesses.

“What was scary was that I couldn’t say with 100% confidence that I wouldn’t have done the same thing.”

Wang recognizes that the biological instinct to procreate is hardwired into our DNA, so that even viewers exempt from the one-child policy still feel the resonating sting of its stakes.

Having a family is a fundamental right, and Wang’s strife mirrors struggles playing out around the globe.

“One Child Nation really shows what happens when a government takes away the power of choice from women,” she says.

“Sadly, that’s not only happening in China; in the United States, women’s control over their own bodies is always being restricted. The other side of the one-child policy, of limiting the right to give birth, is limiting access to reproductive healthcare.”

Her work bridges the gap between the east and west, locating a universal common ground in bodily autonomy.

Her work bridges the gap between the east and west, locating a universal common ground in bodily autonomy.

In creating this connection, Wang hopes to diminish the trans-continental shock she felt at the outset of her own process.

By making the world a little smaller, she hopes everyone watching her film can experience the same blooming of empathy that made this difficult project worthwhile for her.

“Every time I make a film in China, it’s almost a process of unlearning what I’ve known in the past. It’s almost like I relearn these things about my history and country first, and then I let the viewers do the same.”

One Child Nation is out now in the US with a UK date to be announced

One Child Nation is out now in the US with a UK date to be announced

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire